11 Physical And Chemical Agents for Microbial Control

Sterilization refers to any process that removes, kills, or deactivates all forms of life (in particular referring to microorganisms such as fungi, bacteria, spores, unicellular eukaryotic organisms such as Plasmodium, etc.) and other biological agents like prions present in a specific surface, object or fluid, for example food or biological culture media. Sterilization can be achieved through various means, including heat, chemicals, irradiation, high pressure, and filtration. Sterilization is distinct from disinfection, sanitization, and pasteurization, in that those methods reduce rather than eliminate all forms of life and biological agents present. After sterilization, an object is referred to as being sterile or aseptic.

Pasteurization or pasteurisation is a process in which packaged and non-packaged foods (such as milk and fruit juice) are treated with mild heat, usually to less than 100 °C (212 °F), to eliminate pathogens and extend shelf life. The process is intended to destroy or deactivate organisms and enzymes that contribute to spoilage or risk of disease, including vegetative bacteria, but not bacterial spores.

A disinfectant is a chemical substance or compound used to inactivate or destroy microorganisms on inert surfaces. Disinfection does not necessarily kill all microorganisms, especially resistant bacterial spores; it is less effective than sterilization, which is an extreme physical or chemical process that kills all types of life. Disinfectants are generally distinguished from other antimicrobial agents such as antibiotics, which destroy microorganisms within the body, and antiseptics, which destroy microorganisms on living tissue. Disinfectants are also different from biocides—the latter are intended to destroy all forms of life, not just microorganisms. Disinfectants work by destroying the cell wall of microbes or interfering with their metabolism. It is also a form of decontamination, and can be defined as the process whereby physical or chemical methods are used to reduce the amount of pathogenic microorganisms on a surface.

Disinfectants can also be used to destroy microorganisms on the skin and mucous membrane, as in the medical dictionary historically the word simply meant that it destroys microbes.

Sanitizers are substances that simultaneously clean and disinfect. Disinfectants kill more germs than sanitizers. Disinfectants are frequently used in hospitals, dental surgeries, kitchens, and bathrooms to kill infectious organisms. Sanitizers are mild compared to disinfectants and are used majorly to clean things which are in human contact whereas disinfectants are concentrated and are used to clean surfaces like floors and building premises.

Bacterial endospores are most resistant to disinfectants, but some fungi, viruses and bacteria also possess some resistance.

An antiseptic (from Greek ἀντί anti, “against” and σηπτικός sēptikos, “putrefactive”) is an antimicrobial substance or compound that is applied to living tissue/skin to reduce the possibility of infection, sepsis, or putrefaction. Antiseptics are generally distinguished from antibiotics by the latter’s ability to safely destroy bacteria within the body, and from disinfectants, which destroy microorganisms found on non-living objects.

Antibacterials include antiseptics that have the proven ability to act against bacteria. Microbicides which destroy virus particles are called viricides or antivirals. Antifungals, also known as antimycotics, are pharmaceutical fungicides used to treat and prevent mycosis (fungal infection).

11.1 Sterilization

One of the first steps toward modernized sterilization was made by Nicolas Appert who discovered that thorough application of heat over a suitable period slowed the decay of foods and various liquids, preserving them for safe consumption for a longer time than was typical. Canning of foods is an extension of the same principle and has helped to reduce food borne illness (“food poisoning”). Other methods of sterilizing foods include food irradiation and high pressure (pascalization). One process by which food is sterilized is heat treatment. Heat treatment ceases bacterial and enzyme activity which then leads to decreasing the chances of low quality foods while maintaining the life of non-perishable foods. One specific type of heat treatment used is UHT (Ultra-High Temperature) sterilization. This type of heat treatment focuses on sterilization over 100 degrees Celsius. Two types of UHT sterilization are moist and dry heat sterilization. During moist heat sterilization, the temperatures that are used vary from 110 to 130 degrees Celsius. Moist heat sterilization takes between 20 and 40 minutes, the time being shorter the higher the temperature. The use of dry heat sterilization uses longer times of susceptibility that may last up to 2 hours and that use much higher temperatures compared to moist heat sterilization. These temperatures may range from 160 to 180 degrees Celsius.

In general, surgical instruments and medications that enter an already aseptic part of the body (such as the bloodstream, or penetrating the skin) must be sterile. Examples of such instruments include scalpels, hypodermic needles, and artificial pacemakers. This is also essential in the manufacture of parenteral pharmaceuticals.

Preparation of injectable medications and intravenous solutions for fluid replacement therapy requires not only sterility but also well-designed containers to prevent entry of adventitious agents after initial product sterilization.

Most medical and surgical devices used in healthcare facilities are made of materials that are able to go under steam sterilization. However, since 1950, there has been an increase in medical devices and instruments made of materials (e.g., plastics) that require low-temperature sterilization. Ethylene oxide gas has been used since the 1950s for heat- and moisture-sensitive medical devices. Within the past 15 years, a number of new, low-temperature sterilization systems (e.g., vaporized hydrogen peroxide, peracetic acid immersion, ozone) have been developed and are being used to sterilize medical devices.

Steam sterilization is the most widely used and the most dependable. Steam sterilization is nontoxic, inexpensive, rapidly microbicidal, sporicidal, and rapidly heats and penetrates fabrics.

The aim of sterilization is the reduction of initially present microorganisms or other potential pathogens. The degree of sterilization is commonly expressed by multiples of the decimal reduction time, or D-value, denoting the time needed to reduce the initial number N0 tenth (10-1) of its original value. Then the number of microorganisms N after sterilization time t is given by:

\[ \frac{N}{N_0}=10^{(-\frac{t}{D})} \]

The D-value is a function of sterilization conditions and varies with the type of microorganism, temperature, water activity, pH etc.. For steam sterilization (see below) typically the temperature, in degrees Celsius, is given as an index.

Theoretically, the likelihood of the survival of an individual microorganism is never zero. To compensate for this, the overkill method is often used. Using the overkill method, sterilization is performed by sterilizing for longer than is required to kill the bioburden present on or in the item being sterilized. This provides a sterility assurance level (SAL) equal to the probability of a non-sterile unit.

For high-risk applications, such as medical devices and injections, a sterility assurance level of at least 10−6 is required by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

11.1.1 Methods of Sterilization

11.1.2 Steam

A widely used method for heat sterilization is the autoclave, sometimes called a converter or steam sterilizer. Autoclaves use steam heated to 121–134 °C (250–273 °F) under pressure. To achieve sterility, the article is placed in a chamber and heated by injected steam until the article reaches a temperature and time setpoint. Almost all the air is removed from the chamber, because air is undesired in the moist heat sterilization process (this is one trait that differs from a typical pressure cooker used for food cooking). The article is held at the temperature setpoint for a period of time which varies depending on what bioburden is present on the article being sterilized and its resistance (D-value) to steam sterilization. A general cycle would be anywhere between 3 and 15 minutes, (depending on the generated heat) at 121 °C (250 °F) at 100 kPa (15 psi), which is sufficient to provide a sterility assurance level of 10−4 for a product with a bioburden of 106 and a D-value of 2.0 minutes. Following sterilization, liquids in a pressurized autoclave must be cooled slowly to avoid boiling over when the pressure is released. This may be achieved by gradually depressurizing the sterilization chamber and allowing liquids to evaporate under a negative pressure, while cooling the contents.

Proper autoclave treatment will inactivate all resistant bacterial spores in addition to fungi, bacteria, and viruses, but is not expected to eliminate all prions, which vary in their resistance. For prion elimination, various recommendations state 121–132 °C (250–270 °F) for 60 minutes or 134 °C (273 °F) for at least 18 minutes. The 263K scrapie prion is inactivated relatively quickly by such sterilization procedures; however, other strains of scrapie, and strains of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CKD) and bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) are more resistant. Using mice as test animals, one experiment showed that heating BSE positive brain tissue at 134–138 °C (273–280 °F) for 18 minutes resulted in only a 2.5 log decrease in prion infectivity.

Most autoclaves have meters and charts that record or display information, particularly temperature and pressure as a function of time. The information is checked to ensure that the conditions required for sterilization have been met. Indicator tape is often placed on the packages of products prior to autoclaving, and some packaging incorporates indicators. The indicator changes color when exposed to steam, providing a visual confirmation.

Bioindicators can also be used to independently confirm autoclave performance. Simple bioindicator devices are commercially available, based on microbial spores. Most contain spores of the heat-resistant microbe Geobacillus stearothermophilus (formerly Bacillus stearothermophilus), which is extremely resistant to steam sterilization. Biological indicators may take the form of glass vials of spores and liquid media, or as spores on strips of paper inside glassine envelopes. These indicators are placed in locations where it is difficult for steam to reach to verify that steam is penetrating there.

For autoclaving, cleaning is critical. Extraneous biological matter or grime may shield organisms from steam penetration. Proper cleaning can be achieved through physical scrubbing, sonication, ultrasound, or pulsed air.

Moist heat causes the destruction of microorganisms by denaturation of macromolecules, primarily proteins. This method is a faster process than dry heat sterilization.

To sterilize waste materials that are chiefly composed of liquid, a purpose-built effluent decontamination system can be utilized. These devices can function using a variety of sterilants, although using heat via steam is most common.

11.1.3 Dry Heat

Dry heat was the first method of sterilization and is a longer process than moist heat sterilization. The destruction of microorganisms through the use of dry heat is a gradual phenomenon. With longer exposure to lethal temperatures, the number of killed microorganisms increases. Forced ventilation of hot air can be used to increase the rate at which heat is transferred to an organism and reduce the temperature and amount of time needed to achieve sterility. At higher temperatures, shorter exposure times are required to kill organisms. This can reduce heat-induced damage to food products.

The standard setting for a hot air oven is at least two hours at 160 °C (320 °F). A rapid method heats air to 190 °C (374 °F) for 6 minutes for unwrapped objects and 12 minutes for wrapped objects. Dry heat has the advantage that it can be used on powders and other heat-stable items that are adversely affected by steam (e.g. it does not cause rusting of steel objects).

11.1.4 Flaming

Flaming is done to inoculation loops and straight-wires in microbiology labs for streaking. Leaving the loop in the flame of a Bunsen burner or alcohol burner until it glows red ensures that any infectious agent is inactivated. This is commonly used for small metal or glass objects, but not for large objects (see Incineration below). However, during the initial heating, infectious material may be sprayed from the wire surface before it is killed, contaminating nearby surfaces and objects. Therefore, special heaters have been developed that surround the inoculating loop with a heated cage, ensuring that such sprayed material does not further contaminate the area. Another problem is that gas flames may leave carbon or other residues on the object if the object is not heated enough. A variation on flaming is to dip the object in a 70% or more concentrated solution of ethanol, then briefly touch the object to a Bunsen burner flame. The ethanol will ignite and burn off rapidly, leaving less residue than a gas flame

11.1.5 Incineration

Incineration is a waste treatment process that involves the combustion of organic substances contained in waste materials. This method also burns any organism to ash. It is used to sterilize medical and other biohazardous waste before it is discarded with non-hazardous waste. Bacteria incinerators are mini furnaces that incinerate and kill off any microorganisms that may be on an inoculating loop or wire.

11.1.6 Tyndallization

Named after John Tyndall, Tyndallization is an obsolete and lengthy process designed to reduce the level of activity of sporulating bacteria that are left by a simple boiling water method. The process involves boiling for a period (typically 20 minutes) at atmospheric pressure, cooling, incubating for a day, and then repeating the process a total of three to four times. The incubation periods are to allow heat-resistant spores surviving the previous boiling period to germinate to form the heat-sensitive vegetative (growing) stage, which can be killed by the next boiling step. This is effective because many spores are stimulated to grow by the heat shock. The procedure only works for media that can support bacterial growth, and will not sterilize non-nutritive substrates like water. Tyndallization is also ineffective against prions.

Glass bead sterilizers Glass bead sterilizers work by heating glass beads to 250 °C (482 °F). Instruments are then quickly doused in these glass beads, which heat the object while physically scraping contaminants off their surface. Glass bead sterilizers were once a common sterilization method employed in dental offices as well as biological laboratories, but are not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to be used as a sterilizers since 1997. They are still popular in European and Israeli dental practices, although there are no current evidence-based guidelines for using this sterilizer.

11.1.7 Chemical Sterilization

Chemicals are also used for sterilization. Heating provides a reliable way to rid objects of all transmissible agents, but it is not always appropriate if it will damage heat-sensitive materials such as biological materials, fiber optics, electronics, and many plastics. In these situations chemicals, either in a gaseous or liquid form, can be used as sterilants. While the use of gas and liquid chemical sterilants avoids the problem of heat damage, users must ensure that the article to be sterilized is chemically compatible with the sterilant being used and that the sterilant is able to reach all surfaces that must be sterilized (typically cannot penetrate packaging). In addition, the use of chemical sterilants poses new challenges for workplace safety, as the properties that make chemicals effective sterilants usually make them harmful to humans. The procedure for removing sterilant residue from the sterilized materials varies depending on the chemical and process that is used.

11.1.8 Ethylene oxide

Ethylene oxide (EO, EtO) gas treatment is one of the common methods used to sterilize, pasteurize, or disinfect items because of its wide range of material compatibility. It is also used to process items that are sensitive to processing with other methods, such as radiation (gamma, electron beam, X-ray), heat (moist or dry), or other chemicals. Ethylene oxide treatment is the most common chemical sterilization method, used for approximately 70% of total sterilizations, and for over 50% of all disposable medical devices.

Ethylene oxide treatment is generally carried out between 30 and 60 °C (86 and 140 °F) with relative humidity above 30% and a gas concentration between 200 and 800 mg/l. Typically, the process lasts for several hours. Ethylene oxide is highly effective, as it penetrates all porous materials, and it can penetrate through some plastic materials and films. Ethylene oxide kills all known microorganisms, such as bacteria (including spores), viruses, and fungi (including yeasts and moulds), and is compatible with almost all materials even when repeatedly applied. It is flammable, toxic, and carcinogenic; however, only with a reported potential for some adverse health effects when not used in compliance with published requirements. Ethylene oxide sterilizers and processes require biological validation after sterilizer installation, significant repairs or process changes.

The traditional process consists of a preconditioning phase (in a separate room or cell), a processing phase (more commonly in a vacuum vessel and sometimes in a pressure rated vessel), and an aeration phase (in a separate room or cell) to remove EO residues and lower by-products such as ethylene chlorohydrin (EC or ECH) and, of lesser importance, ethylene glycol (EG). An alternative process, known as all-in-one processing, also exists for some products whereby all three phases are performed in the vacuum or pressure rated vessel. This latter option can facilitate faster overall processing time and residue dissipation.

The most common EO processing method is the gas chamber method. To benefit from economies of scale, EO has traditionally been delivered by filling a large chamber with a combination of gaseous EO either as pure EO, or with other gases used as diluents; diluents include chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs), and carbon dioxide.

Ethylene oxide is still widely used by medical device manufacturers. Since EO is explosive at concentrations above 3%, EO was traditionally supplied with an inert carrier gas, such as a CFC or HCFC. The use of CFCs or HCFCs as the carrier gas was banned because of concerns of ozone depletion. These halogenated hydrocarbons are being replaced by systems using 100% EO, because of regulations and the high cost of the blends. In hospitals, most EO sterilizers use single-use cartridges because of the convenience and ease of use compared to the former plumbed gas cylinders of EO blends.

It is important to adhere to patient and healthcare personnel government specified limits of EO residues in and/or on processed products, operator exposure after processing, during storage and handling of EO gas cylinders, and environmental emissions produced when using EO.

The U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has set the permissible exposure limit (PEL) at 1 ppm – calculated as an eight-hour time-weighted average (TWA) – and 5 ppm as a 15-minute excursion limit (EL). The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health’s (NIOSH) immediately dangerous to life and health limit (IDLH) for EO is 800 ppm. The odor threshold is around 500 ppm, so EO is imperceptible until concentrations are well above the OSHA PEL. Therefore, OSHA recommends that continuous gas monitoring systems be used to protect workers using EO for processing.

11.1.9 Nitrogen Dioxide

Nitrogen dioxide (NO2) gas is a rapid and effective sterilant for use against a wide range of microorganisms, including common bacteria, viruses, and spores. The unique physical properties of NO2 gas allow for sterilant dispersion in an enclosed environment at room temperature and atmospheric pressure. The mechanism for lethality is the degradation of DNA in the spore core through nitration of the phosphate backbone, which kills the exposed organism as it absorbs NO2. This degradations occurs at even very low concentrations of the gas. NO2 has a boiling point of 21 °C (70 °F) at sea level, which results in a relatively highly saturated vapour pressure at ambient temperature. Because of this, liquid NO2 may be used as a convenient source for the sterilant gas. Liquid NO2 is often referred to by the name of its dimer, dinitrogen tetroxide (N2O4). Additionally, the low levels of concentration required, coupled with the high vapour pressure, assures that no condensation occurs on the devices being sterilized. This means that no aeration of the devices is required immediately following the sterilization cycle. NO2 is also less corrosive than other sterilant gases, and is compatible with most medical materials and adhesives.

The most-resistant organism (MRO) to sterilization with NO2 gas is the spore of Geobacillus stearothermophilus, which is the same MRO for both steam and hydrogen peroxide sterilization processes. The spore form of G. stearothermophilus has been well characterized over the years as a biological indicator in sterilization applications. Microbial inactivation of G. stearothermophilus with NO2 gas proceeds rapidly in a log-linear fashion, as is typical of other sterilization processes. Noxilizer, Inc. has commercialized this technology to offer contract sterilization services for medical devices at its Baltimore, Maryland (U.S.) facility. This has been demonstrated in Noxilizer’s lab in multiple studies and is supported by published reports from other labs. These same properties also allow for quicker removal of the sterilant and residual gases through aeration of the enclosed environment. The combination of rapid lethality and easy removal of the gas allows for shorter overall cycle times during the sterilization (or decontamination) process and a lower level of sterilant residuals than are found with other sterilization methods. Eniware, LLC has developed a portable, power-free sterilizer that uses no electricity, heat or water. The 25 liter unit makes sterilization of surgical instruments possible for austere forward surgical teams, in health centers throughout the world with intermittent or no electricity and in disaster relief and humanitarian crisis situations. The four hour cycle uses a single use gas generation ampoule and a disposable scrubber to remove nitrogen dioxide gas.

11.1.10 Ozone

Ozone is used in industrial settings to sterilize water and air, as well as a disinfectant for surfaces. It has the benefit of being able to oxidize most organic matter. On the other hand, it is a toxic and unstable gas that must be produced on-site, so it is not practical to use in many settings.

Ozone offers many advantages as a sterilant gas; ozone is a very efficient sterilant because of its strong oxidizing properties (E=2.076 vs SHE) capable of destroying a wide range of pathogens, including prions, without the need for handling hazardous chemicals since the ozone is generated within the sterilizer from medical-grade oxygen. The high reactivity of ozone means that waste ozone can be destroyed by passing over a simple catalyst that reverts it to oxygen and ensures that the cycle time is relatively short. The disadvantage of using ozone is that the gas is very reactive and very hazardous. The NIOSH’s immediately dangerous to life and health limit (IDLH) for ozone is 5 ppm, 160 times smaller than the 800 ppm IDLH for ethylene oxide. NIOSH and OSHA has set the PEL for ozone at 0.1 ppm, calculated as an eight-hour time-weighted average. The sterilant gas manufacturers include many safety features in their products but prudent practice is to provide continuous monitoring of exposure to ozone, in order to provide a rapid warning in the event of a leak. Monitors for determining workplace exposure to ozone are commercially available.

11.1.11 Glutaraldehyde And Formaldehyde

Glutaraldehyde and formaldehyde solutions (also used as fixatives) are accepted liquid sterilizing agents, provided that the immersion time is sufficiently long. To kill all spores in a clear liquid can take up to 22 hours with glutaraldehyde and even longer with formaldehyde. The presence of solid particles may lengthen the required period or render the treatment ineffective. Sterilization of blocks of tissue can take much longer, due to the time required for the fixative to penetrate. Glutaraldehyde and formaldehyde are volatile, and toxic by both skin contact and inhalation. Glutaraldehyde has a short shelf-life (<2 weeks), and is expensive. Formaldehyde is less expensive and has a much longer shelf-life if some methanol is added to inhibit polymerization to paraformaldehyde, but is much more volatile. Formaldehyde is also used as a gaseous sterilizing agent; in this case, it is prepared on-site by depolymerization of solid paraformaldehyde. Many vaccines, such as the original Salk polio vaccine, are sterilized with formaldehyde.

11.1.12 Hydrogen Peroxide

Hydrogen peroxide, in both liquid and as vaporized hydrogen peroxide (VHP), is another chemical sterilizing agent. Hydrogen peroxide is a strong oxidant, which allows it to destroy a wide range of pathogens. Hydrogen peroxide is used to sterilize heat- or temperature-sensitive articles, such as rigid endoscopes. In medical sterilization, hydrogen peroxide is used at higher concentrations, ranging from around 35% up to 90%. The biggest advantage of hydrogen peroxide as a sterilant is the short cycle time. Whereas the cycle time for ethylene oxide may be 10 to 15 hours, some modern hydrogen peroxide sterilizers have a cycle time as short as 28 minutes.

Drawbacks of hydrogen peroxide include material compatibility, a lower capability for penetration and operator health risks. Products containing cellulose, such as paper, cannot be sterilized using VHP and products containing nylon may become brittle. The penetrating ability of hydrogen peroxide is not as good as ethylene oxide and so there are limitations on the length and diameter of the lumen of objects that can be effectively sterilized. Hydrogen peroxide is a primary irritant and the contact of the liquid solution with skin will cause bleaching or ulceration depending on the concentration and contact time. It is relatively non-toxic when diluted to low concentrations, but is a dangerous oxidizer at high concentrations (> 10% w/w). The vapour is also hazardous, primarily affecting the eyes and respiratory system. Even short term exposures can be hazardous and NIOSH has set the IDLH at 75 ppm, less than one tenth the IDLH for ethylene oxide (800 ppm). Prolonged exposure to lower concentrations can cause permanent lung damage and consequently, OSHA has set the permissible exposure limit to 1.0 ppm, calculated as an eight-hour time-weighted average. Sterilizer manufacturers go to great lengths to make their products safe through careful design and incorporation of many safety features, though there are still workplace exposures of hydrogen peroxide from gas sterilizers documented in the FDA MAUDE database. When using any type of gas sterilizer, prudent work practices should include good ventilation, a continuous gas monitor for hydrogen peroxide and good work practices and training.

Vaporized hydrogen peroxide (VHP) is used to sterilize large enclosed and sealed areas, such as entire rooms and aircraft interiors.

Although toxic, VHP breaks down in a short time to water and oxygen.

11.1.13 Peracetic Acid

Peracetic acid (0.2%) is a recognized sterilant by the FDA for use in sterilizing medical devices such as endoscopes. Peracetic acid which is also known as peroxyacetic acid is a chemical compound often used in disinfectants such as sanitizers. It is most commonly produced by the reaction of acetic acid and hydrogen peroxide with each other by using an acid catalyst. Peracetic acid is never sold in unstabilized solutions which is why it is considered to be environmentally friendly. Peracetic acid is a colorless liquid and the molecular formula of peracetic acid is C2H4O3 or CH3COOOH. More recently, peracetic acid is being used throughout the world as more people are using fumigation to decontaminate surfaces to reduce the risk of Covid-19 and other diseases.

11.1.14 Potential For Chemical Sterilization Of Prions

Prions are highly resistant to chemical sterilization. Treatment with aldehydes, such as formaldehyde, have actually been shown to increase prion resistance. Hydrogen peroxide (3%) for one hour was shown to be ineffective, providing less than 3 logs (10−3) reduction in contamination. Iodine, formaldehyde, glutaraldehyde, and peracetic acid also fail this test (one hour treatment). Only chlorine, phenolic compounds, guanidinium thiocyanate, and sodium hydroxide reduce prion levels by more than 4 logs; chlorine (too corrosive to use on certain objects) and sodium hydroxide are the most consistent. Many studies have shown the effectiveness of sodium hydroxide.

11.1.15 Radiation Sterilization

Sterilization can be achieved using electromagnetic radiation, such as ultraviolet light, X-rays and gamma rays, or irradiation by subatomic particles such as by electron beams. Electromagnetic or particulate radiation can be energetic enough to ionize atoms or molecules (ionizing radiation), or less energetic (non-ionizing radiation).

11.1.16 Non-Ionizing Radiation Sterilization

Further information: Ultraviolet germicidal irradiation Ultraviolet light irradiation (UV, from a germicidal lamp) is useful for sterilization of surfaces and some transparent objects. Many objects that are transparent to visible light absorb UV. UV irradiation is routinely used to sterilize the interiors of biological safety cabinets between uses, but is ineffective in shaded areas, including areas under dirt (which may become polymerized after prolonged irradiation, so that it is very difficult to remove). It also damages some plastics, such as polystyrene foam if exposed for prolonged periods of time.

11.1.17 Ionizing Radiation Sterilization

The safety of irradiation facilities is regulated by the International Atomic Energy Agency of the United Nations and monitored by the different national Nuclear Regulatory Commissions (NRC). The radiation exposure accidents that have occurred in the past are documented by the agency and thoroughly analyzed to determine the cause and improvement potential. Such improvements are then mandated to retrofit existing facilities and future design.

Gamma radiation is very penetrating, and is commonly used for sterilization of disposable medical equipment, such as syringes, needles, cannulas and IV sets, and food. It is emitted by a radioisotope, usually cobalt-60 (60Co) or caesium-137 (137Cs), which have photon energies of up to 1.3 and 0.66 MeV, respectively.

Use of a radioisotope requires shielding for the safety of the operators while in use and in storage. With most designs, the radioisotope is lowered into a water-filled source storage pool, which absorbs radiation and allows maintenance personnel to enter the radiation shield. One variant keeps the radioisotope under water at all times and lowers the product to be irradiated in the water in hermetically-sealed bells; no further shielding is required for such designs. Other uncommonly used designs use dry storage, providing movable shields that reduce radiation levels in areas of the irradiation chamber. An incident in Decatur, Georgia, US, where water-soluble caesium-137 leaked into the source storage pool, requiring NRC intervention has led to use of this radioisotope being almost entirely discontinued in favour of the more costly, non-water-soluble cobalt-60. Cobalt-60 gamma photons have about twice the energy, and hence greater penetrating range, of caesium-137-produced radiation.

Electron beam processing is also commonly used for sterilization. Electron beams use an on-off technology and provide a much higher dosing rate than gamma or X-rays. Due to the higher dose rate, less exposure time is needed and thereby any potential degradation to polymers is reduced. Because electrons carry a charge, electron beams are less penetrating than both gamma and X-rays. Facilities rely on substantial concrete shields to protect workers and the environment from radiation exposure.

High-energy X-rays (produced by bremsstrahlung) allow irradiation of large packages and pallet loads of medical devices. They are sufficiently penetrating to treat multiple pallet loads of low-density packages with very good dose uniformity ratios. X-ray sterilization does not require chemical or radioactive material: high-energy X-rays are generated at high intensity by an X-ray generator that does not require shielding when not in use. X-rays are generated by bombarding a dense material (target) such as tantalum or tungsten with high-energy electrons, in a process known as bremsstrahlung conversion. These systems are energy-inefficient, requiring much more electrical energy than other systems for the same result.

Irradiation with X-rays, gamma rays, or electrons does not make materials radioactive, because the energy used is too low. Generally an energy of at least 10 MeV is needed to induce radioactivity in a material. Neutrons and very high-energy particles can make materials radioactive, but have good penetration, whereas lower energy particles (other than neutrons) cannot make materials radioactive, but have poorer penetration.

Sterilization by irradiation with gamma rays may however affect material properties.

Irradiation is used by the United States Postal Service to sterilize mail in the Washington, D.C. area. Some foods (e.g. spices and ground meats) are sterilized by irradiation.

Subatomic particles may be more or less penetrating and may be generated by a radioisotope or a device, depending upon the type of particle.

11.1.18 Sterile filtration

Fluids that would be damaged by heat, irradiation or chemical sterilization, such as drug solution, can be sterilized by microfiltration using membrane filters. This method is commonly used for heat labile pharmaceuticals and protein solutions in medicinal drug processing. A microfilter with pore size of usually 0.22 µm will effectively remove microorganisms. Some staphylococcal species have, however, been shown to be flexible enough to pass through 0.22 µm filters. In the processing of biologics, viruses must be removed or inactivated, requiring the use of nanofilters with a smaller pore size (20–50 nm). Smaller pore sizes lower the flow rate, so in order to achieve higher total throughput or to avoid premature blockage, pre-filters might be used to protect small pore membrane filters. Tangential flow filtration (TFF) and alternating tangential flow (ATF) systems also reduce particulate accumulation and blockage.

Membrane filters used in production processes are commonly made from materials such as mixed cellulose ester or polyethersulfone (PES). The filtration equipment and the filters themselves may be purchased as pre-sterilized disposable units in sealed packaging or must be sterilized by the user, generally by autoclaving at a temperature that does not damage the fragile filter membranes. To ensure proper functioning of the filter, the membrane filters are integrity tested post-use and sometimes before use. The nondestructive integrity test assures the filter is undamaged and is a regulatory requirement. Typically, terminal pharmaceutical sterile filtration is performed inside of a cleanroom to prevent contamination.

Instruments that have undergone sterilization can be maintained in such condition by containment in sealed packaging until use.

Aseptic technique is the act of maintaining sterility during procedures.

11.2 Pasteurization

The process was named after the French microbiologist, Louis Pasteur, whose research in the 1860s demonstrated that thermal processing would deactivate unwanted microorganisms in wine. Spoilage enzymes are also inactivated during pasteurization. Today, pasteurization is used widely in the dairy industry and other food processing industries to achieve food preservation and food safety.

By the year 1999, most liquid products were heat treated in a continuous system where heat can be applied using a plate heat exchanger or the direct or indirect use of hot water and steam. Due to the mild heat, there are minor changes to the nutritional quality and sensory characteristics of the treated foods. Pascalization or high pressure processing (HPP) and pulsed electric field (PEF) are non-thermal processes that are also used to pasteurize foods.

The process of heating wine for preservation purposes has been known in China since AD 1117, and was documented in Japan in the diary Tamonin-nikki, written by a series of monks between 1478 and 1618.

Much later, in 1768, research performed by Italian priest and scientist Lazzaro Spallanzani proved a product could be made “sterile” after thermal processing. Spallanzani boiled meat broth for one hour, sealed the container immediately after boiling, and noticed that the broth did not spoil and was free from microorganisms. In 1795, a Parisian chef and confectioner named Nicolas Appert began experimenting with ways to preserve foodstuffs, succeeding with soups, vegetables, juices, dairy products, jellies, jams, and syrups. He placed the food in glass jars, sealed them with cork and sealing wax and placed them in boiling water. In that same year, the French military offered a cash prize of 12,000 francs for a new method to preserve food. After some 14 or 15 years of experimenting, Appert submitted his invention and won the prize in January 1810. Later that year, Appert published L’Art de conserver les substances animales et végétales (“The Art of Preserving Animal and Vegetable Substances”). This was the first cookbook of its kind on modern food preservation methods.

La Maison Appert (English: The House of Appert), in the town of Massy, near Paris, became the first food-bottling factory in the world, preserving a variety of foods in sealed bottles. Appert’s method was to fill thick, large-mouthed glass bottles with produce of every description, ranging from beef and fowl to eggs, milk and prepared dishes. He left air space at the top of the bottle, and the cork would then be sealed firmly in the jar by using a vise. The bottle was then wrapped in canvas to protect it while it was dunked into boiling water and then boiled for as much time as Appert deemed appropriate for cooking the contents thoroughly. Appert patented his method, sometimes called appertisation in his honor.

Appert’s method was so simple and workable that it quickly became widespread. In 1810, British inventor and merchant Peter Durand, also of French origin, patented his own method, but this time in a tin can, so creating the modern-day process of canning foods. In 1812, Englishmen Bryan Donkin and John Hall purchased both patents and began producing preserves. Just a decade later, Appert’s method of canning had made its way to America.[full citation needed] Tin can production was not common until the beginning of the 20th century, partly because a hammer and chisel were needed to open cans until the invention of a can opener by Robert Yeates in 1855.

A less aggressive method was developed by French chemist Louis Pasteur during an 1864 summer holiday in Arbois. To remedy the frequent acidity of the local aged wines, he found out experimentally that it is sufficient to heat a young wine to only about 50–60 °C (122–140 °F) for a short time to kill the microbes, and that the wine could subsequently be aged without sacrificing the final quality. In honour of Pasteur, this process is known as “pasteurization”. Pasteurization was originally used as a way of preventing wine and beer from souring, and it would be many years before milk was pasteurized. In the United States in the 1870s, before milk was regulated, it was common for milk to contain substances intended to mask spoilage.

Milk is an excellent medium for microbial growth, and when it is stored at ambient temperature bacteria and other pathogens soon proliferate. The US Centers for Disease Control (CDC) says improperly handled raw milk is responsible for nearly three times more hospitalizations than any other food-borne disease source, making it one of the world’s most dangerous food products. Diseases prevented by pasteurization can include tuberculosis, brucellosis, diphtheria, scarlet fever, and Q-fever; it also kills the harmful bacteria Salmonella, Listeria, Yersinia, Campylobacter, Staphylococcus aureus, and Escherichia coli O157:H7, among others.

Prior to industrialization, dairy cows were kept in urban areas to limit the time between milk production and consumption, hence the risk of disease transmission via raw milk was reduced. As urban densities increased and supply chains lengthened to the distance from country to city, raw milk (often days old) became recognized as a source of disease. For example, between 1912 and 1937, some 65,000 people died of tuberculosis contracted from consuming milk in England and Wales alone. Because tuberculosis has a long incubation period in humans, it was difficult to link unpasteurized milk consumption with the disease. In 1892, chemist Ernst Lederle experimentally inoculated milk from tuberculosis-diseased cows into guinea pigs, which caused them to develop the disease. In 1910, Lederle, then in the role of Commissioner of Health, introduced mandatory pasteurization of milk in New York City.

Developed countries adopted milk pasteurization to prevent such disease and loss of life, and as a result milk is now considered a safer food. A traditional form of pasteurization by scalding and straining of cream to increase the keeping qualities of butter was practiced in Great Britain in the 18th century and was introduced to Boston in the British Colonies by 1773, although it was not widely practiced in the United States for the next 20 years. Pasteurization of milk was suggested by Franz von Soxhlet in 1886. In the early 20th century, Milton Joseph Rosenau established the standards – i.e. low-temperature, slow heating at 60 °C (140 °F) for 20 minutes – for the pasteurization of milk while at the United States Marine Hospital Service, notably in his publication of The Milk Question (1912). States in the U.S. soon began enacting mandatory dairy pasteurization laws, with the first in 1947, and in 1973 the U.S. federal government required pasteurization of milk used in any interstate commerce.

The shelf life of refrigerated pasteurized milk is greater than that of raw milk. For example, high-temperature, short-time (HTST) pasteurized milk typically has a refrigerated shelf life of two to three weeks, whereas ultra-pasteurized milk can last much longer, sometimes two to three months. When ultra-heat treatment (UHT) is combined with sterile handling and container technology (such as aseptic packaging), it can even be stored non-refrigerated for up to 9 months.

According to the Centers for Disease Control, between 1998 and 2011, 79% of dairy-related disease outbreaks in the United States were due to raw milk or cheese products. They report 148 outbreaks and 2,384 illnesses (with 284 requiring hospitalization), as well as two deaths due to raw milk or cheese products during the same time period.

Medical equipment Medical equipment, notably respiratory and anesthesia equipment, is often disinfected using hot water, as an alternative to chemical disinfection. The temperature is raised to 70 °C (158 °F) for 30 minutes.

Pasteurization processPasteurization is a mild heat treatment of liquid foods (both packaged and unpackaged) where products are typically heated to below 100 °C. The heat treatment and cooling process are designed to inhibit a phase change of the product. The acidity of the food determines the parameters (time and temperature) of the heat treatment as well as the duration of shelf life. Parameters also take into account nutritional and sensory qualities that are sensitive to heat.

In acidic foods (pH <4.6), such as fruit juice and beer, the heat treatments are designed to inactivate enzymes (pectin methylesterase and polygalacturonase in fruit juices) and destroy spoilage microbes (yeast and lactobacillus). Due to the low pH of acidic foods, pathogens are unable to grow. The shelf-life is thereby extended several weeks. In less acidic foods (pH >4.6), such as milk and liquid eggs, the heat treatments are designed to destroy pathogens and spoilage organisms (yeast and molds). Not all spoilage organisms are destroyed under pasteurization parameters, thus subsequent refrigeration is necessary.

Equipment Food can be pasteurized in two ways: either before or after being packaged into containers. When food is packaged in glass, hot water is used to lower the risk of thermal shock. Plastics and metals are also used to package foods, and these are generally pasteurized with steam or hot water since the risk of thermal shock is low.

Most liquid foods are pasteurized using continuous systems that have a heating zone, hold tube, and cooling zone, after which the product is filled into the package. Plate heat exchangers are used for low-viscosity products such as animal milks, nut milks and juices. A plate heat exchanger is composed of many thin vertical stainless steel plates which separate the liquid from the heating or cooling medium. Scraped surface heat exchangers contain an inner rotating shaft in the tube, and serve to scrape highly viscous material which might accumulate on the wall of the tube.

Shell or tube heat exchangers are designed for the pasteurization of foods that are non-Newtonian fluids, such as dairy products, tomato ketchup and baby foods. A tube heat exchanger is made up of concentric stainless steel tubes. Food passes through the inner tube while the heating/cooling medium is circulated through the outer or inner tube.

The benefits of using a heat exchanger to pasteurize non-packaged foods versus pasteurizing foods in containers are:

Heat exchangers provide uniform treatment, and there is greater flexibility with regards to the products which can be pasteurized on these plates The process is more energy-efficient compared to pasteurizing foods in packaged containers Greater throughput After being heated in a heat exchanger, the product flows through a hold tube for a set period of time to achieve the required treatment. If pasteurization temperature or time is not achieved, a flow diversion valve is utilized to divert under-processed product back to the raw product tank. If the product is adequately processed, it is cooled in a heat exchanger, then filled.

High-temperature short-time (HTST) pasteurization, such as that used for milk (71.5 °C (160.7 °F) for 15 seconds) ensures safety of milk and provides a refrigerated shelf life of approximately two weeks. In ultra-high-temperature (UHT) pasteurization, milk is pasteurized at 135 °C (275 °F) for 1–2 seconds, which provides the same level of safety, but along with the packaging, extends shelf life to three months under refrigeration.

Verification Direct microbiological techniques are the ultimate measurement of pathogen contamination, but these are costly and time-consuming, which means that products have a reduced shelf-life by the time pasteurization is verified.

As a result of the unsuitability of microbiological techniques, milk pasteurization efficacy is typically monitored by checking for the presence of alkaline phosphatase, which is denatured by pasteurization. Destruction of alkaline phosphatase ensures the destruction of common milk pathogens. Therefore, the presence of alkaline phosphatase is an ideal indicator of pasteurization efficacy. For liquid eggs, the effectiveness of the heat treatment is measured by the residual activity of α-amylase.

Efficacy against pathogenic bacteria During the early 20th century, there was no robust knowledge of what time and temperature combinations would inactivate pathogenic bacteria in milk, and so a number of different pasteurization standards were in use. By 1943, both HTST pasteurization conditions of 72 °C (162 °F) for 15 seconds, as well as batch pasteurization conditions of 63 °C (145 °F) for 30 minutes, were confirmed by studies of the complete thermal death (as best as could be measured at that time) for a range of pathogenic bacteria in milk. Complete inactivation of Coxiella burnetii (which was thought at the time to cause Q fever by oral ingestion of infected milk) as well as of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (which causes tuberculosis) were later demonstrated. For all practical purposes, these conditions were adequate for destroying almost all yeasts, molds, and common spoilage bacteria and also for ensuring adequate destruction of common pathogenic, heat-resistant organisms. However, the microbiological techniques used until the 1960s did not allow for the actual reduction of bacteria to be enumerated. Demonstration of the extent of inactivation of pathogenic bacteria by milk pasteurization came from a study of surviving bacteria in milk that was heat-treated after being deliberately spiked with high levels of the most heat-resistant strains of the most significant milk-borne pathogens.

The mean log10 reductions and temperatures of inactivation of the major milk-borne pathogens during a 15-second treatment are:

- Staphylococcus aureus > 6.7 at 66.5 °C (151.7 °F)

- Yersinia enterocolitica > 6.8 at 62.5 °C (144.5 °F)

- pathogenic Escherichia coli > 6.8 at 65 °C (149 °F)

- Cronobacter sakazakii > 6.7 at 67.5 °C (153.5 °F)

- Listeria monocytogenes > 6.9 at 65.5 °C (149.9 °F)

- Salmonella ser. Typhimurium > 6.9 at 61.5 °C (142.7 °F)

(A log10 reduction between 6 and 7 means that 1 bacterium out of 1 million (106) to 10 million (107) bacteria survive the treatment.)

The Codex Alimentarius Code of Hygienic Practice for Milk notes that milk pasteurization is designed to achieve at least a 5 log10 reduction of Coxiella burnetii. The Code also notes that: “The minimum pasteurization conditions are those having bactericidal effects equivalent to heating every particle of the milk to 72 °C for 15 seconds (continuous flow pasteurization) or 63 °C for 30 minutes (batch pasteurization)” and that “To ensure that each particle is sufficiently heated, the milk flow in heat exchangers should be turbulent, i.e. the Reynolds number should be sufficiently high”. The point about turbulent flow is important because simplistic laboratory studies of heat inactivation that use test tubes, without flow, will have less bacterial inactivation than larger-scale experiments that seek to replicate conditions of commercial pasteurization.

As a precaution, modern HTST pasteurization processes must be designed with flow-rate restriction as well as divert valves which ensure that the milk is heated evenly and that no part of the milk is subject to a shorter time or a lower temperature. It is common for the temperatures to exceed 72 °C by 1.5 °C or 2 °C.

Double pasteurization Since pasteurization is not sterilization, and does not kill spores, a second “double” pasteurization will extend the shelf life by killing spores that have germinated.

The acceptance of double pasteurization vary by jurisdiction. In places where it is allowed, an initial pasteurization usually happens when the milk was collected at the farm, so that it does not spoil before processing. Many countries disallow such milk to be simply labelled as “pasturized”, so thermization, a lower-temperature process, is used instead.

11.3 Disinfectants

Disinfectants are used to rapidly kill bacteria. They kill off the bacteria by causing the proteins to become damaged and outer layers of the bacteria cell to rupture. The DNA material subsequently leaks out. In wastewater treatment, a disinfection step with chlorine, ultra-violet (UV) radiation or ozonation can be included as tertiary treatment to remove pathogens from wastewater, for example if it is to be discharged to a river or the sea where there body contact immersion recreations is practiced (Europe) or reused to irrigate golf courses (US). An alternative term used in the sanitation sector for disinfection of waste streams, sewage sludge or fecal sludge is sanitisation or sanitization.

Sterilant

Sterilant means a chemical agent which is used to sterilise critical medical devices or medical instruments. A sterilant kills all micro-organisms with the result that the sterility assurance level of a microbial survivor is less than 10^-6. Sterilant gases are not within this scope.

Low level disinfectant

Low level disinfectant means a disinfectant that rapidly kills most vegetative bacteria as well as medium sized lipid containing viruses, when used according to labelling. It cannot be relied upon to destroy, within a practical period, bacterial endospores, mycobacteria, fungi, or all small nonlipid viruses.

Intermediate level disinfectant

Intermediate level disinfectant means a disinfectant that kills all microbial pathogens except bacterial endospores, when used as recommended by the manufacturer. It is bactericidal, tuberculocidal, fungicidal (against asexual spores but not necessarily dried chlamydospores or sexual spores), and virucidal.

High level disinfectant

High level disinfectant means a disinfectant that kills all microbial pathogens, except large numbers of bacterial endospores when used as recommended by its manufacturer.

Instrument grade

Instrument grade disinfectant means:

- a disinfectant which is used to reprocess reusable therapeutic devices; and

- when associated with the words “low”, “intermediate” or “high” means “low”, “intermediate” or “high” level disinfectant respectively.

Hospital grade

Hospital grade disinfectant means a disinfectant that is suitable for general purpose disinfection of building and fitting surfaces, and purposes not involving instruments or surfaces likely to come into contact with broken skin.

Household/commercial grade

Household/commercial grade disinfectant means a disinfectant that is suitable for general purpose disinfection of building or fitting surfaces, and for other purposes, in premises or involving procedures other than those specified for a hospital grade disinfectant, but is not:

an antibacterial clothes preparation; or * a sanitary fluid; or * a sanitary powder; or * a sanitiser

One way to compare disinfectants is to compare how well they do against a known disinfectant and rate them accordingly. Phenol is the standard, and the corresponding rating system is called the “Phenol coefficient”. The disinfectant to be tested is compared with phenol on a standard microbe (usually Salmonella typhi or Staphylococcus aureus). Disinfectants that are more effective than phenol have a coefficient > 1. Those that are less effective have a coefficient < 1.

The standard European approach for disinfectant validation consists of a basic suspension test, a quantitative suspension test (with low and high levels of organic material added to act as ‘interfering substances’) and a two part simulated-use surface test.

A less specific measurement of effectiveness is the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) classification into either high, intermediate or low levels of disinfection. “High-level disinfection kills all organisms, except high levels of bacterial spores” and is done with a chemical germicide marketed as a sterilant by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). “Intermediate-level disinfection kills mycobacteria, most viruses, and bacteria with a chemical germicide registered as a ‘tuberculocide’ by the Environmental Protection Agency. Low-level disinfection kills some viruses and bacteria with a chemical germicide registered as a hospital disinfectant by the EPA.”

An alternative assessment is to measure the Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of disinfectants against selected (and representative) microbial species, such as through the use of microbroth dilution testing. However, those methods are obtained at standard inoculum levels without considering the inoculum effect. More informative methods are nowadays in demand to determine the minimum disinfectant dose as a function of the density of the target microbial species.

A perfect disinfectant would also offer complete and full microbiological sterilisation, without harming humans and useful form of life, be inexpensive, and noncorrosive. However, most disinfectants are also, by nature, potentially harmful (even toxic) to humans or animals. Most modern household disinfectants contain denatonium, an exceptionally bitter substance added to discourage ingestion, as a safety measure. Those that are used indoors should never be mixed with other cleaning products as chemical reactions can occur. The choice of disinfectant to be used depends on the particular situation. Some disinfectants have a wide spectrum (kill many different types of microorganisms), while others kill a smaller range of disease-causing organisms but are preferred for other properties (they may be non-corrosive, non-toxic, or inexpensive).

There are arguments for creating or maintaining conditions that are not conducive to bacterial survival and multiplication, rather than attempting to kill them with chemicals. Bacteria can increase in number very quickly, which enables them to evolve rapidly. Should some bacteria survive a chemical attack, they give rise to new generations composed completely of bacteria that have resistance to the particular chemical used. Under a sustained chemical attack, the surviving bacteria in successive generations are increasingly resistant to the chemical used, and ultimately the chemical is rendered ineffective. For this reason, some question the wisdom of impregnating cloths, cutting boards and worktops in the home with bactericidal chemicals.

11.3.1 Types Of Disinfectants

11.3.2 Air Disinfectants

Air disinfectants are typically chemical substances capable of disinfecting microorganisms suspended in the air. Disinfectants are generally assumed to be limited to use on surfaces, but that is not the case. In 1928, a study found that airborne microorganisms could be killed using mists of dilute bleach. An air disinfectant must be dispersed either as an aerosol or vapour at a sufficient concentration in the air to cause the number of viable infectious microorganisms to be significantly reduced.

In the 1940s and early 1950s, further studies showed inactivation of diverse bacteria, influenza virus, and Penicillium chrysogenum (previously P. notatum) mold fungus using various glycols, principally propylene glycol and triethylene glycol. In principle, these chemical substances are ideal air disinfectants because they have both high lethality to microorganisms and low mammalian toxicity.

Although glycols are effective air disinfectants in controlled laboratory environments, it is more difficult to use them effectively in real-world environments because the disinfection of air is sensitive to continuous action. Continuous action in real-world environments with outside air exchanges at door, HVAC, and window interfaces, and in the presence of materials that adsorb and remove glycols from the air, poses engineering challenges that are not critical for surface disinfection. The engineering challenge associated with creating a sufficient concentration of the glycol vapours in the air have not to date been sufficiently addressed.

11.3.3 Alcohols

Alcohol and alcohol plus Quaternary ammonium cation based compounds comprise a class of proven surface sanitizers and disinfectants approved by the EPA and the Centers for Disease Control for use as a hospital grade disinfectant. Alcohols are most effective when combined with distilled water to facilitate diffusion through the cell membrane; 100% alcohol typically denatures only external membrane proteins. A mixture of 70% ethanol or isopropanol diluted in water is effective against a wide spectrum of bacteria, though higher concentrations are often needed to disinfect wet surfaces. Additionally, high-concentration mixtures (such as 80% ethanol + 5% isopropanol) are required to effectively inactivate lipid-enveloped viruses (such as HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C).

The efficacy of alcohol is enhanced when in solution with the wetting agent dodecanoic acid (coconut soap). The synergistic effect of 29.4% ethanol with dodecanoic acid is effective against a broad spectrum of bacteria, fungi, and viruses. Further testing is being performed against Clostridium difficile (C.Diff) spores with higher concentrations of ethanol and dodecanoic acid, which proved effective with a contact time of ten minutes.

11.3.4 Aldehydes

Aldehydes, such as formaldehyde and glutaraldehyde, have a wide microbicidal activity and are sporicidal and fungicidal. They are partly inactivated by organic matter and have slight residual activity.

Some bacteria have developed resistance to glutaraldehyde, and it has been found that glutaraldehyde can cause asthma and other health hazards, hence ortho-phthalaldehyde is replacing glutaraldehyde.

11.3.5 Oxidizing agents

Oxidizing agents act by oxidizing the cell membrane of microorganisms, which results in a loss of structure and leads to cell lysis and death. A large number of disinfectants operate in this way. Chlorine and oxygen are strong oxidizers, so their compounds figure heavily here.

- Electrolyzed water or “Anolyte” is an oxidizing, acidic hypochlorite solution made by electrolysis of sodium chloride into sodium hypochlorite and hypochlorous acid. Anolyte has an oxidation-reduction potential of +600 to +1200 mV and a typical pH range of 3.5––8.5, but the most potent solution is produced at a controlled pH 5.0–6.3 where the predominant oxychlorine species is hypochlorous acid.

- Hydrogen peroxide is used in hospitals to disinfect surfaces and it is used in solution alone or in combination with other chemicals as a high level disinfectant. Hydrogen peroxide is sometimes mixed with colloidal silver. It is often preferred because it causes far fewer allergic reactions than alternative disinfectants. Also used in the food packaging industry to disinfect foil containers. A 3% solution is also used as an antiseptic.

- Hydrogen peroxide vapor is used as a medical sterilant and as room disinfectant. Hydrogen peroxide has the advantage that it decomposes to form oxygen and water thus leaving no long term residues, but hydrogen peroxide as with most other strong oxidants is hazardous, and solutions are a primary irritant. The vapor is hazardous to the respiratory system and eyes and consequently the OSHA permissible exposure limit is 1 ppm (29 CFR 1910.1000 Table Z-1) calculated as an eight-hour time weighted average and the NIOSH immediately dangerous to life and health limit is 75 ppm. Therefore, engineering controls, personal protective equipment, gas monitoring etc. should be employed where high concentrations of hydrogen peroxide are used in the workplace. Vaporized hydrogen peroxide is one of the chemicals approved for decontamination of anthrax spores from contaminated buildings, such as occurred during the 2001 anthrax attacks in the U.S. It has also been shown to be effective in removing exotic animal viruses, such as avian influenza and Newcastle disease from equipment and surfaces.

- The antimicrobial action of hydrogen peroxide can be enhanced by surfactants and organic acids. The resulting chemistry is known as Accelerated Hydrogen Peroxide. A 2% solution, stabilized for extended use, achieves high-level disinfection in 5 minutes, and is suitable for disinfecting medical equipment made from hard plastic, such as in endoscopes. The evidence available suggests that products based on Accelerated Hydrogen Peroxide, apart from being good germicides, are safer for humans and benign to the environment.

- Ozone is a gas used for disinfecting water, laundry, foods, air, and surfaces. It is chemically aggressive and destroys many organic compounds, resulting in rapid decolorization and deodorization in addition to disinfection. Ozone decomposes relatively quickly. However, due to this characteristic of ozone, tap water chlorination cannot be entirely replaced by ozonation, as the ozone would decompose already in the water piping. Instead, it is used to remove the bulk of oxidizable matter from the water, which would produce small amounts of organochlorides if treated with chlorine only. Regardless, ozone has a very wide range of applications from municipal to industrial water treatment due to its powerful reactivity.

- Potassium permanganate (KMnO4) is a purplish-black crystalline powder that colours everything it touches, through a strong oxidising action. This includes staining “stainless” steel, which somehow limits its use and makes it necessary to use plastic or glass containers. It is used to disinfect aquariums and is used in some community swimming pools as a foot disinfectant before entering the pool. Typically, a large shallow basin of KMnO4 / water solution is kept near the pool ladder. Participants are required to step in the basin and then go into the pool. Additionally, it is widely used to disinfect community water ponds and wells in tropical countries, as well as to disinfect the mouth before pulling out teeth. It can be applied to wounds in dilute solution.

11.3.6 Peroxy And Peroxo Acids

Peroxycarboxylic acids and inorganic peroxo acids are strong oxidants and extremely effective disinfectants.

- Peroxyformic acid

- Peracetic acid

- Peroxypropionic acid

- Monoperoxyglutaric acid

- Monoperoxysuccinic acid

- Peroxybenzoic acid

- Peroxyanisic acid

- Chloroperbenzoic acid

- Monoperoxyphthalic acid

- Peroxymonosulfuric acid

11.3.7 Phenolics

Phenolics are active ingredients in some household disinfectants. They are also found in some mouthwashes and in disinfectant soap and handwashes. Phenols are toxic to cats and newborn humans

- Phenol is probably the oldest known disinfectant as it was first used by Lister, when it was called carbolic acid. It is rather corrosive to the skin and sometimes toxic to sensitive people. Impure preparations of phenol were originally made from coal tar, and these contained low concentrations of other aromatic hydrocarbons including benzene, which is an IARC Group 1 carcinogen.

- o-Phenylphenol is often used instead of phenol, since it is somewhat less corrosive.

- Chloroxylenol is the principal ingredient in Dettol, a household disinfectant and antiseptic.

- Hexachlorophene is a phenolic that was once used as a germicidal additive to some household products but was banned due to suspected harmful effects.

- Thymol, derived from the herb thyme, is the active ingredient in some “broad spectrum” disinfectants that often bear ecological claims. It is used as a stabilizer in pharmaceutic preparations. It has been used for its antiseptic, antibacterial, and antifungal actions, and was formerly used as a vermifuge.

- Amylmetacresol is found in Strepsils, a throat disinfectant.

- Although not a phenol, 2,4-dichlorobenzyl alcohol has similar effects as phenols, but it cannot inactivate viruses.

11.3.8 Quaternary ammonium compounds

Quaternary ammonium compounds (“quats”), such as benzalkonium chloride, are a large group of related compounds. Some concentrated formulations have been shown to be effective low-level disinfectants. Quaternary ammonia at or above 200ppm plus alcohol solutions exhibit efficacy against difficult to kill non-enveloped viruses such as norovirus, rotavirus, or polio virus. Newer synergous, low-alcohol formulations are highly effective broad-spectrum disinfectants with quick contact times (3–5 minutes) against bacteria, enveloped viruses, pathogenic fungi, and mycobacteria. Quats are biocides that also kill algae and are used as an additive in large-scale industrial water systems to minimize undesired biological growth.

11.3.9 Inorganic compounds

11.3.10 Chlorine

This group comprises aqueous solution of chlorine, hypochlorite, or hypochlorous acid. Occasionally, chlorine-releasing compounds and their salts are included in this group. Frequently, a concentration of < 1 ppm of available chlorine is sufficient to kill bacteria and viruses, spores and mycobacteria requiring higher concentrations. Chlorine has been used for applications, such as the deactivation of pathogens in drinking water, swimming pool water and wastewater, for the disinfection of household areas and for textile bleaching

- Sodium hypochlorite

- Calcium hypochlorite

- Monochloramine

- Chloramine-T

- Trichloroisocyanuric acid

- Chlorine dioxide

- Hypochlorous acid

11.3.11 Iodine

- Iodine

- Iodophors

11.3.12 Acids And Bases

- Sodium hydroxide

- Potassium hydroxide

- Calcium hydroxide

- Magnesium hydroxide

- Sulfurous acid

- Sulfur dioxide

11.3.13 Metals

Most metals, especially those with high atomic weights can inhibit the growth of pathogens by disrupting their metabolism.

11.3.14 Terpenes

- Thymol

- Pine oil

11.3.15 Other

The biguanide polymer polyaminopropyl biguanide is specifically bactericidal at very low concentrations (10 mg/l). It has a unique method of action: The polymer strands are incorporated into the bacterial cell wall, which disrupts the membrane and reduces its permeability, which has a lethal effect to bacteria. It is also known to bind to bacterial DNA, alter its transcription, and cause lethal DNA damage. It has very low toxicity to higher organisms such as human cells, which have more complex and protective membranes.

Common sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3) has antifungal properties, and some antiviral and antibacterial properties, though those are too weak to be effective at a home environment.

11.3.16 Non-chemical

Ultraviolet germicidal irradiation is the use of high-intensity shortwave ultraviolet light for disinfecting smooth surfaces such as dental tools, but not porous materials that are opaque to the light such as wood or foam. Ultraviolet light is also used for municipal water treatment. Ultraviolet light fixtures are often present in microbiology labs, and are activated only when there are no occupants in a room (e.g., at night).

Heat treatment can be used for disinfection and sterilization.

The phrase “sunlight is the best disinfectant” was popularized in 1913 by United States Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis and later advocates of government transparency. While sunlight’s ultraviolet rays can act as a disinfectant, the Earth’s ozone layer blocks the rays’ most effective wavelengths. Ultraviolet light-emitting machines, such as those used to disinfect some hospital rooms, make for better disinfectants than sunlight.

11.4 Antiseptics

An antiseptic (from Greek ἀντί anti, “against” and σηπτικός sēptikos, “putrefactive”) is an antimicrobial substance or compound that is applied to living tissue/skin to reduce the possibility of infection, sepsis, or putrefaction. Antiseptics are generally distinguished from antibiotics by the latter’s ability to safely destroy bacteria within the body, and from disinfectants, which destroy microorganisms found on non-living objects.

Antibacterials include antiseptics that have the proven ability to act against bacteria. Microbicides which destroy virus particles are called viricides or antivirals. Antifungals, also known as antimycotics, are pharmaceutical fungicides used to treat and prevent mycosis (fungal infection).

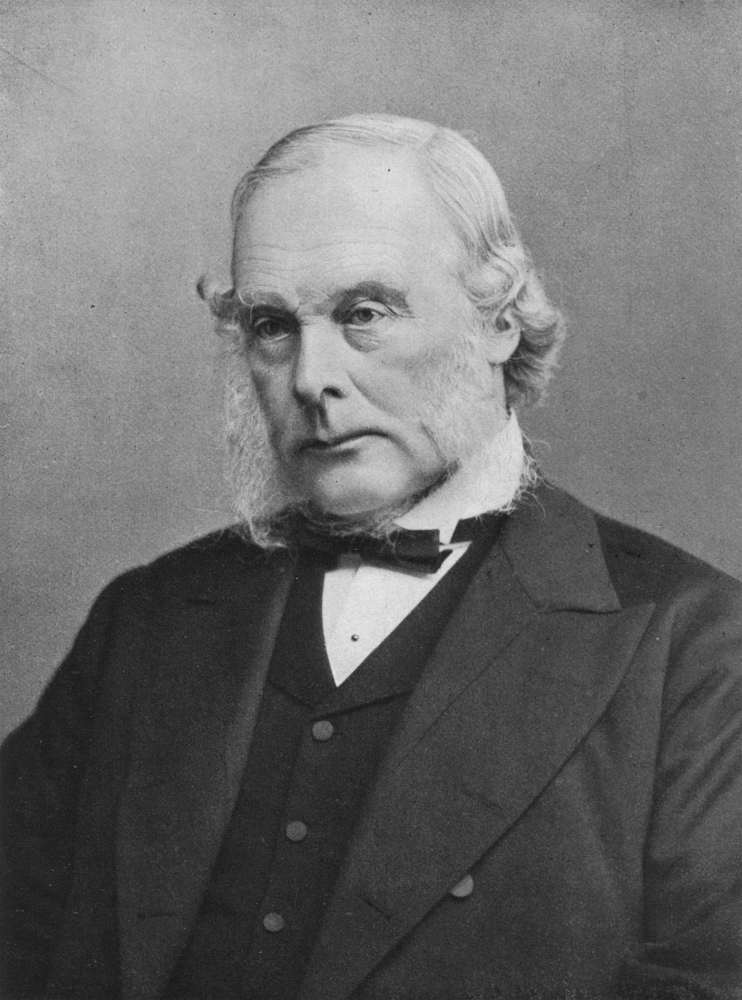

Figure 11.2: The surgeon Joseph Lister in 1902.

The widespread introduction of antiseptic surgical methods was initiated by the publishing of the paper Antiseptic Principle of the Practice of Surgery in 1867 by Joseph Lister, which was inspired by Louis Pasteur’s germ theory of putrefaction. In this paper, Lister advocated the use of carbolic acid (phenol) as a method of ensuring that any germs present were killed. Some of this work was anticipated by:

- Ancient Greek physicians Galen (circa 130–200) and Hippocrates (circa 400 BC) and Sumerian clay tablets dating from 2150 BC that advocate the use of similar techniques.

- Medieval surgeons Hugh of Lucca, Theoderic of Servia, and his pupil Henri de Mondeville were opponents of Galen’s opinion that pus was important to healing, which had led ancient and medieval surgeons to let pus remain in wounds. They advocated draining and cleaning the wound edges with wine, dressing the wound after suturing, if necessary and leaving the dressing on for ten days, soaking it in warm wine all the while, before changing it. Their theories were bitterly opposed by Galenist Guy de Chauliac and others trained in the classical tradition.

- Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr., who published The Contagiousness of Puerperal Fever in 1843

- Florence Nightingale, who contributed substantially to the report of the Royal Commission on the Health of the Army (1856–1857), based on her earlier work

- Ignaz Semmelweis, who published his work The Cause, Concept and Prophylaxis of Childbed Fever in 1861, summarizing experiments and observations since 1847]

Antiseptics can be subdivided into about eight classes of materials. These classes can be subdivided according to their mechanism of action: small molecules that indescrimantly react with organic compounds and kill microorganisms (peroxides, iodine, phenols) and more complex molecules that disrupt the cell walls of the bacteria.

- Phenols such as phenol itself (as introduced by Lister) and triclosan, hexachlorophene, chlorocresol, and chloroxylenol. The latter is used for skin disinfection and cleaning surgical instruments. It is also used within a number of household disinfectants and wound cleaners.

- Diguanides including chlorhexidine gluconate, a bacteriocidal antiseptic which (with an alcoholic solvent) is the most effective at reducing the risk of infection after surgery. It is also used in mouthwashes to treat inflammation of the gums (gingivitis). Polyhexanide (polyhexamethylene biguanide, PHMB) is an antimicrobial compound suitable for clinical use in critically colonized or infected acute and chronic wounds. The physicochemical action on the bacterial envelope prevents or impedes the development of resistant bacterial strains.

- Quinolines such as hydroxyquinolone, dequalium chloride, or chlorquinaldol.

- Alcohols, including ethanol and 2-propanol/isopropanol are sometimes referred to as surgical spirit. They are used to disinfect the skin before injections, among other uses.

- Peroxides, such as hydrogen peroxide and benzoyl peroxide. Commonly, 3% solutions of hydrogen peroxide have been used in household first aid for scrapes, etc. However, the strong oxidization causes scar formation and increases healing time during fetal development.

- Iodine, especially in the form of povidone-iodine, is widely used because it is well tolerated, does not negatively affect wound healing, leaves a deposit of active iodine, thereby creating the so-called “remnant”, or persistent, effect, and has wide scope of antimicrobial activity. The traditional iodine antiseptic is an alcohol solution (called tincture of iodine) or as Lugol’s iodine solution. Some studies do not recommend disinfecting minor wounds with iodine because of concern that it may induce scar tissue formation and increase healing time. However, concentrations of 1% iodine or less have not been shown to increase healing time and are not otherwise distinguishable from treatment with saline. Iodine will kill all principal pathogens and, given enough time, even spores, which are considered to be the most difficult form of microorganisms to be inactivated by disinfectants and antiseptics.

- Octenidine dihydrochloride, currently increasingly used in continental Europe, often as a chlorhexidine substitute.

- Quat salts such as benzalkonium chloride, cetylpyridinium chloride, or cetrimide. These surfactants disrupt cell walls.