4 An Introduction To Prokaryotic Cells And Microorganisms

4.1 Basic Characteristics Of Life

In the past, there have been many attempts to define what is meant by “life” through obsolete concepts such as odic force, hylomorphism, spontaneous generation and vitalism, that have now been disproved by biological discoveries. Aristotle is considered to be the first person to classify organisms. Later, Carl Linnaeus introduced his system of binomial nomenclature for the classification of species. Eventually new groups and categories of life were discovered, such as cells and microorganisms, forcing dramatic revisions of the structure of relationships between living organisms. Though currently only known on Earth, life need not be restricted to it, and many scientists speculate in the existence of extraterrestrial life. Artificial life is a computer simulation or human-made reconstruction of any aspect of life, which is often used to examine systems related to natural life.

Death is the permanent termination of all biological functions which sustain an organism, and as such, is the end of its life. Extinction is the term describing the dying out of a group or taxon, usually a species. Fossils are the preserved remains or traces of organisms.

The definition of life has long been a challenge for scientists and philosophers, with many varied definitions put forward. This is partially because life is a process, not a substance. This is complicated by a lack of knowledge of the characteristics of living entities, if any, that may have developed outside of Earth. Philosophical definitions of life have also been put forward, with similar difficulties on how to distinguish living things from the non-living. Legal definitions of life have also been described and debated, though these generally focus on the decision to declare a human dead, and the legal ramifications of this decision.

Since there is no unequivocal definition of life, most current definitions in biology are descriptive. Life is considered a characteristic of something that preserves, furthers or reinforces its existence in the given environment. This characteristic exhibits all or most of the following traits:

- Homeostasis: regulation of the internal environment to maintain a constant state; for example, sweating to reduce temperature

- Organization: being structurally composed of one or more cells – the basic units of life

- Metabolism: transformation of energy by converting chemicals and energy into cellular components (anabolism) and decomposing organic matter (catabolism). Living things require energy to maintain internal organization (homeostasis) and to produce the other phenomena associated with life.

- Growth: maintenance of a higher rate of anabolism than catabolism. A growing organism increases in size in all of its parts, rather than simply accumulating matter.

- Adaptation: the ability to change over time in response to the environment. This ability is fundamental to the process of evolution and is determined by the organism’s heredity, diet, and external factors.

- Response to stimuli: a response can take many forms, from the contraction of a unicellular organism to external chemicals, to complex reactions involving all the senses of multicellular organisms. A response is often expressed by motion; for example, the leaves of a plant turning toward the sun (phototropism), and chemotaxis.

- Reproduction: the ability to produce new individual organisms, either asexually from a single parent organism or sexually from two parent organisms.

These complex processes, called physiological functions, have underlying physical and chemical bases, as well as signaling and control mechanisms that are essential to maintaining life.

More than 99% of all species of life forms, amounting to over five billion species, that ever lived on Earth are estimated to be extinct.

Although the number of Earth’s catalogued species of lifeforms is between 1.2 million and 2 million, the total number of species in the planet is uncertain. Estimates range from 8 million to 100 million, with a more narrow range between 10 and 14 million, but it may be as high as 1 trillion (with only one-thousandth of one percent of the species described) according to studies realized in May 2016. The total number of related DNA base pairs on Earth is estimated at 5.0 x 1037 and weighs 50 billion tonnes. In comparison, the total mass of the biosphere has been estimated to be as much as 4 TtC (trillion tons of carbon). In July 2016, scientists reported identifying a set of 355 genes from the Last Universal Common Ancestor (LUCA) of all organisms living on Earth.

4.2 Origin Of Life

The Ancient Greeks believed that living things could spontaneously come into being from nonliving matter, and that the goddess Gaia could make life arise spontaneously from stones – a process known as Generatio spontanea. Aristotle disagreed, but he still believed that creatures could arise from dissimilar organisms or from soil. Variations of this concept of spontaneous generation still existed as late as the 17th century, but towards the end of the 17th century, a series of observations and arguments began that eventually discredited such ideas. This advance in scientific understanding was met with much opposition, with personal beliefs and individual prejudices often obscuring the facts.

William Harvey (1578–1657) was an early proponent of all life beginning from an egg, omne vivum ex ovo. Francesco Redi, an Italian physician, proved as early as 1668 that higher forms of life did not originate spontaneously by demonstrating that maggots come from eggs of flies. But proponents of spontaneous generation claimed that this did not apply to microbes and continued to hold that these could arise spontaneously. Attempts to disprove the spontaneous generation of life from non-life continued in the early 19th century with observations and experiments by Franz Schulze and Theodor Schwann. In 1745, John Needham added chicken broth to a flask and boiled it. He then let it cool and waited. Microbes grew, and he proposed it as an example of spontaneous generation. In 1768, Lazzaro Spallanzani repeated Needham’s experiment but removed all the air from the flask. No growth occurred. In 1854, Heinrich G. F. Schröder (1810–1885) and Theodor von Dusch, and in 1859, Schröder alone, repeated the Helmholtz filtration experiment and showed that living particles can be removed from air by filtering it through cotton-wool.

In 1864, Louis Pasteur finally announced the results of his scientific experiments. In a series of experiments similar to those performed earlier by Needham and Spallanzani, Pasteur demonstrated that life does not arise in areas that have not been contaminated by existing life. Pasteur’s empirical results were summarized in the phrase Omne vivum ex vivo, Latin for “all life [is] from life”.

All known life forms share fundamental molecular mechanisms, reflecting their common descent; based on these observations, hypotheses on the origin of life attempt to find a mechanism explaining the formation of a universal common ancestor, from simple organic molecules via pre-cellular life to protocells and metabolism. Models have been divided into “genes-first” and “metabolism-first” categories, but a recent trend is the emergence of hybrid models that combine both categories.

Life on Earth is based on carbon and water. Carbon provides stable frameworks for complex chemicals and can be easily extracted from the environment, especially from carbon dioxide. There is no other chemical element whose properties are similar enough to carbon’s to be called an analogue; silicon, the element directly below carbon on the periodic table, does not form very many complex stable molecules, and because most of its compounds are water-insoluble and because silicon dioxide is a hard and abrasive solid in contrast to carbon dioxide at temperatures associated with living things, it would be more difficult for organisms to extract. The elements boron and phosphorus have more complex chemistries, but suffer from other limitations relative to carbon. Water is an excellent solvent and has two other useful properties: the fact that ice floats enables aquatic organisms to survive beneath it in winter; and its molecules have electrically negative and positive ends, which enables it to form a wider range of compounds than other solvents can. Other good solvents, such as ammonia, are liquid only at such low temperatures that chemical reactions may be too slow to sustain life, and lack water’s other advantages. Organisms based on alternative biochemistry may, however, be possible on other planets.

Abiogenesis, or informally the origin of life, is the natural process of life arising from non-living matter, such as simple organic compounds. The prevailing scientific hypothesis is that the transition from non-living to living entities was not a single event, but a gradual process of increasing complexity. Although the occurrence of abiogenesis is uncontroversial among scientists, its possible mechanisms are poorly understood. There are several principles and hypotheses for how abiogenesis could have occurred. Life on Earth first appeared as early as 4.28 billion years ago, soon after ocean formation 4.41 billion years ago, and not long after the formation of the Earth 4.54 billion years ago. The earliest known life forms are microfossils of bacteria.

There is no current scientific consensus as to how life originated. However, many accepted scientific models build on the Miller–Urey experiment and the work of Sidney Fox, which show that conditions on the primitive Earth favored chemical reactions that synthesize amino acids and other organic compounds from inorganic precursors, and phospholipids spontaneously form lipid bilayers, the basic structure of a cell membrane.

The classic 1952 Miller–Urey experiment (Figure 4.1) demonstrated that most amino acids, the chemical constituents of the proteins used in all living organisms, can be synthesized from inorganic compounds under conditions intended to replicate those of the early Earth. The experiment used water (H2O), methane (CH4), ammonia (NH3), and hydrogen (H2). The chemicals were all sealed inside a sterile 5-liter glass flask connected to a 500 ml flask half-full of water. The water in the smaller flask was heated to induce evaporation, and the water vapour was allowed to enter the larger flask. Continuous electrical sparks were fired between the electrodes to simulate lightning in the water vapour and gaseous mixture, and then the simulated atmosphere was cooled again so that the water condensed and trickled into a U-shaped trap at the bottom of the apparatus.

After a day, the solution collected at the trap had turned pink in colour, and after a week of continuous operation the solution was deep red and turbid. The boiling flask was then removed, and mercuric chloride was added to prevent microbial contamination. The reaction was stopped by adding barium hydroxide and sulfuric acid, and evaporated to remove impurities. Using paper chromatography, Miller identified five amino acids present in the solution: glycine, α-alanine and β-alanine were positively identified, while aspartic acid and α-aminobutyric acid (AABA) were less certain, due to the spots being faint.Complex organic molecules occur in the Solar System and in interstellar space, and these molecules may have provided starting material for the development of life on Earth.

Figure 4.1: The Miller–Urey experiment was a chemical experiment that simulated the conditions thought at the time (1952) to be present on the early Earth and tested the chemical origin of life under those conditions. The experiment at the time supported Alexander Oparin’s and J. B. S. Haldane’s hypothesis that putative conditions on the primitive Earth favoured chemical reactions that synthesized more complex organic compounds from simpler inorganic precursors. Considered to be the classic experiment investigating abiogenesis, it was conducted in 1952 by Stanley Miller, with assistance from Harold Urey, at the University of Chicago and later the University of California, San Diego and published the following year.

Living organisms synthesize proteins, which are polymers of amino acids using instructions encoded by deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA). Protein synthesis entails intermediary ribonucleic acid (RNA) polymers. One possibility for how life began is that genes originated first, followed by proteins; the alternative being that proteins came first and then genes.

However, because genes and proteins are both required to produce the other, the problem of considering which came first is like that of the chicken or the egg. Most scientists have adopted the hypothesis that because of this, it is unlikely that genes and proteins arose independently.

Therefore, a possibility, first suggested by Francis Crick, is that the first life was based on RNA, which has the DNA-like properties of information storage and the catalytic properties of some proteins. This is called the RNA world hypothesis, and it is supported by the observation that many of the most critical components of cells (those that evolve the slowest) are composed mostly or entirely of RNA. Also, many critical cofactors (ATP, Acetyl-CoA, NADH, etc.) are either nucleotides or substances clearly related to them. The catalytic properties of RNA had not yet been demonstrated when the hypothesis was first proposed, but they were confirmed by Thomas Cech in 1986.

One issue with the RNA world hypothesis is that synthesis of RNA from simple inorganic precursors is more difficult than for other organic molecules. One reason for this is that RNA precursors are very stable and react with each other very slowly under ambient conditions, and it has also been proposed that living organisms consisted of other molecules before RNA. However, the successful synthesis of certain RNA molecules under the conditions that existed prior to life on Earth has been achieved by adding alternative precursors in a specified order with the precursor phosphate present throughout the reaction. This study makes the RNA world hypothesis more plausible.

Geological findings in 2013 showed that reactive phosphorus species (like phosphite) were in abundance in the ocean before 3.5 Ga, and that Schreibersite easily reacts with aqueous glycerol to generate phosphite and glycerol 3-phosphate. It is hypothesized that Schreibersite-containing meteorites from the Late Heavy Bombardment could have provided early reduced phosphorus, which could react with prebiotic organic molecules to form phosphorylated biomolecules, like RNA.

In 2009, experiments demonstrated Darwinian evolution of a two-component system of RNA enzymes (ribozymes) in vitro. The work was performed in the laboratory of Gerald Joyce, who stated “This is the first example, outside of biology, of evolutionary adaptation in a molecular genetic system.”

Prebiotic compounds may have originated extraterrestrially. NASA findings in 2011, based on studies with meteorites found on Earth, suggest DNA and RNA components (adenine, guanine and related organic molecules) may be formed in outer space.

In March 2015, NASA scientists reported that, for the first time, complex DNA and RNA organic compounds of life, including uracil, cytosine and thymine, have been formed in the laboratory under outer space conditions, using starting chemicals, such as pyrimidine, found in meteorites. Pyrimidine, like polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), the most carbon-rich chemical found in the universe, may have been formed in red giants or in interstellar dust and gas clouds, according to the scientists.

According to the panspermia hypothesis, microscopic life—distributed by meteoroids, asteroids and other small Solar System bodies—may exist throughout the universe.

Since its primordial beginnings, life on Earth has changed its environment on a geologic time scale, but it has also adapted to survive in most ecosystems and conditions. Some microorganisms, called extremophiles, thrive in physically or geochemically extreme environments that are detrimental to most other life on Earth. The cell is considered the structural and functional unit of life. There are two kinds of cells, prokaryotic and eukaryotic, both of which consist of cytoplasm enclosed within a membrane and contain many biomolecules such as proteins and nucleic acids. Cells reproduce through a process of cell division, in which the parent cell divides into two or more daughter cells.

Figure 4.2: Cartoons of a eukaryotic and prokaryotic cell.

4.3 The Foundations Of Modern Biology

4.3.1 The Cell Theory

Cell theory states that the cell is the fundamental unit of life, that all living things are composed of one or more cells, and that all cells arise from pre-existing cells through cell division. In multicellular organisms, every cell in the organism’s body derives ultimately from a single cell in a fertilized egg. The cell is also considered to be the basic unit in many pathological processes. In addition, the phenomenon of energy flow occurs in cells in processes that are part of the function known as metabolism. Finally, cells contain hereditary information (DNA), which is passed from cell to cell during cell division. Research into the origin of life, abiogenesis, amounts to an attempt to discover the origin of the first cells.

Cells are the basic unit of structure in every living thing, and all cells arise from pre-existing cells by division. Cell theory was formulated by Henri Dutrochet, Theodor Schwann, Matthias Jakob Schleiden, Rudolf Virchow and others during the early nineteenth century, and subsequently became widely accepted. The activity of an organism depends on the total activity of its cells, with energy flow occurring within and between them. Cells contain hereditary information that is carried forward as a genetic code during cell division.

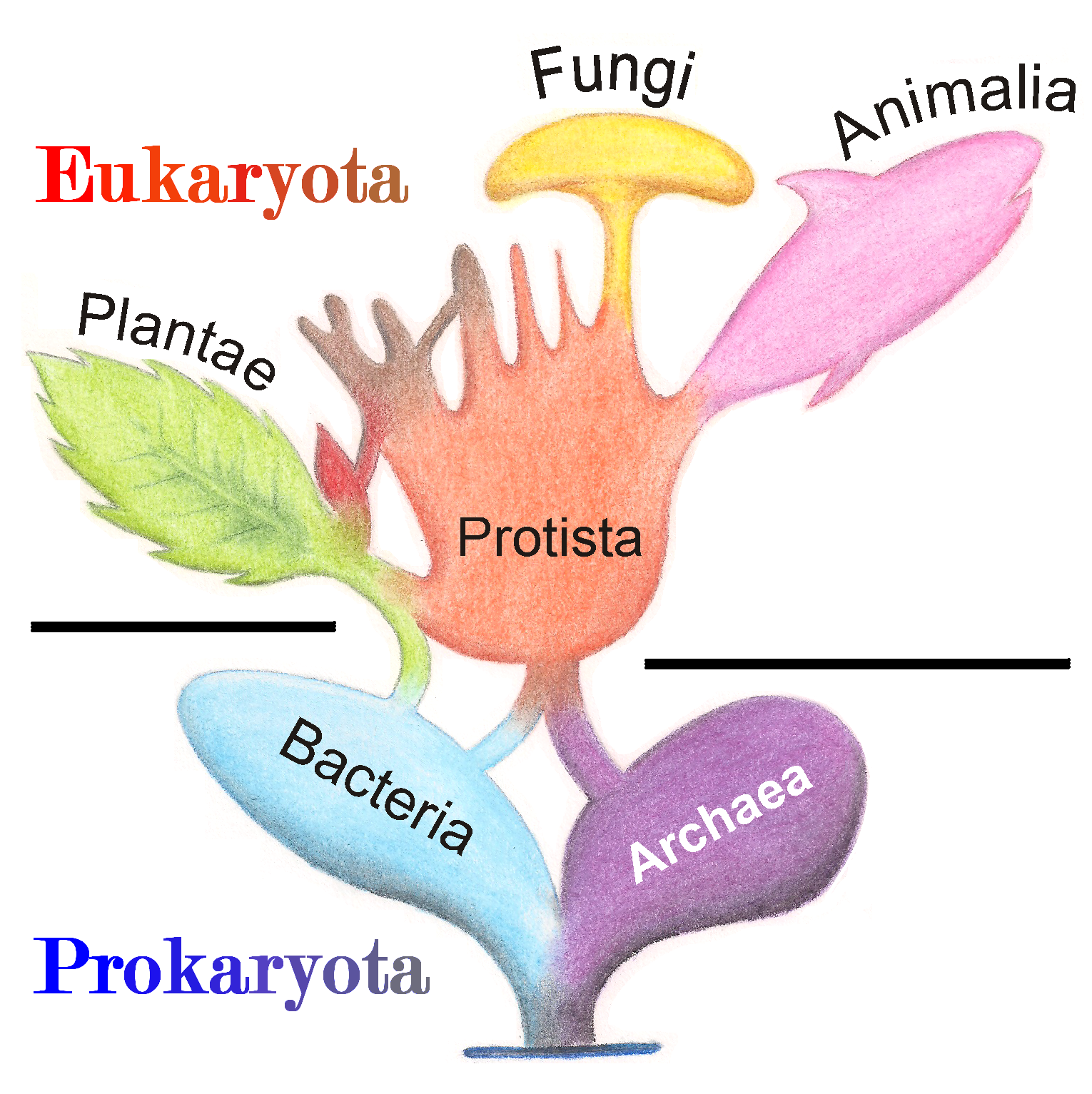

There are two primary types of cells. Prokaryotes lack a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles, although they have circular DNA and ribosomes. Bacteria and Archaea are two domains of prokaryotes. The other primary type of cells are the eukaryotes, which have distinct nuclei bound by a nuclear membrane and membrane-bound organelles, including mitochondria, chloroplasts, lysosomes, rough and smooth endoplasmic reticulum, and vacuoles. In addition, they possess organized chromosomes that store genetic material. All species of large complex organisms are eukaryotes, including animals, plants and fungi, though most species of eukaryote are protist microorganisms. The conventional model is that eukaryotes evolved from prokaryotes, with the main organelles of the eukaryotes forming through endosymbiosis between bacteria and the progenitor eukaryotic cell.

Figure 4.3: Tree diagram illustrating the evolutionary relationship of living organisms.

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living cells of an organism. Scientific opinions differ on whether viruses are a form of life, or organic structures that interact with living organisms. They have been described as “organisms at the edge of life”, since they resemble organisms in that they possess genes, evolve by natural selection, and reproduce by creating multiple copies of themselves through self-assembly. Although they have genes, they do not have a cellular structure, which is seen as the basic unit of life. Viruses do not have their own metabolism, and require a host cell to make new products. They therefore cannot naturally reproduce outside a host cell—although bacterial species such as rickettsia and chlamydia are considered living organisms despite the same limitation. Accepted forms of life use cell division to reproduce, whereas viruses spontaneously assemble within cells. They differ from autonomous growth of crystals as they inherit genetic mutations while being subject to natural selection. Virus self-assembly within host cells has implications for the study of the origin of life, as it lends further credence to the hypothesis that life could have started as self-assembling organic molecules.

The molecular mechanisms of cell biology are based on proteins which are synthesized by the ribosomes through an enzyme-catalyzed process called protein biosynthesis. A sequence of amino acids is assembled and joined together based upon gene expression of the cell’s nucleic acid. In eukaryotic cells, these proteins may then be transported and processed through the Golgi apparatus in preparation for dispatch to their destination.

Cells reproduce through a process of cell division in which the parent cell divides into two or more daughter cells. For prokaryotes, cell division occurs through a process of fission in which the DNA is replicated, then the two copies are attached to parts of the cell membrane. In eukaryotes, a more complex process of mitosis is followed. However, the end result is the same; the resulting cell copies are identical to each other and to the original cell (except for mutations), and both are capable of further division following an interphase period.

Multicellular organisms may have first evolved through the formation of colonies of identical cells. These cells can form group organisms through cell adhesion. The individual members of a colony are capable of surviving on their own, whereas the members of a true multi-cellular organism have developed specializations, making them dependent on the remainder of the organism for survival. Such organisms are formed clonally or from a single germ cell that is capable of forming the various specialized cells that form the adult organism. This specialization allows multicellular organisms to exploit resources more efficiently than single cells. In January 2016, scientists reported that, about 800 million years ago, a minor genetic change in a single molecule, called GK-PID, may have allowed organisms to go from a single cell organism to one of many cells.

Cells have evolved methods to perceive and respond to their microenvironment, thereby enhancing their adaptability. Cell signaling coordinates cellular activities, and hence governs the basic functions of multicellular organisms. Signaling between cells can occur through direct cell contact using juxtacrine signalling, or indirectly through the exchange of agents as in the endocrine system. In more complex organisms, coordination of activities can occur through a dedicated nervous system.

4.3.2 The Theory Of Evolution

A central organizing concept in biology is that life changes and develops through evolution, and that all life-forms known have a common origin. The theory of evolution postulates that all organisms on the Earth, both living and extinct, have descended from a common ancestor or an ancestral gene pool. This universal common ancestor of all organisms is believed to have appeared about 3.5 billion years ago. Biologists regard the ubiquity of the genetic code as definitive evidence in favor of the theory of universal common descent for all bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes.

The term “evolution” was introduced into the scientific lexicon by Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck in 1809, and fifty years later Charles Darwin posited a scientific model of natural selection as evolution’s driving force. Alfred Russel Wallace independently reached the same conclusions and is recognized as the co-discoverer of this concept. Evolution is now used to explain the great variations of life found on Earth.

Darwin theorized that species flourish or die when subjected to the processes of natural selection or selective breeding. Genetic drift was embraced as an additional mechanism of evolutionary development in the modern synthesis of the theory.

The evolutionary history of the species—which describes the characteristics of the various species from which it descended—together with its genealogical relationship to every other species is known as its phylogeny. Widely varied approaches to biology generate information about phylogeny. These include the comparisons of DNA sequences, a product of molecular biology (more particularly genomics), and comparisons of fossils or other records of ancient organisms, a product of paleontology. Biologists organize and analyze evolutionary relationships through various methods, including phylogenetics, phenetics, and cladistics

Evolution is relevant to the understanding of the natural history of life forms and to the understanding of the organization of current life forms. But, those organizations can only be understood in light of how they came to be by way of the process of evolution. Consequently, evolution is central to all fields of biology.

The evolutionary history of life on Earth traces the processes by which living and fossil organisms evolved, from the earliest emergence of life to the present. Earth formed about 4.5 billion years (Ga) ago and evidence suggests life emerged prior to 3.7 Ga. (Although there is some evidence of life as early as 4.1 to 4.28 Ga, it remains controversial due to the possible non-biological formation of the purported fossils.) The similarities among all known present-day species indicate that they have diverged through the process of evolution from a common ancestor. Approximately 1 trillion species currently live on Earth of which only 1.75–1.8 million have been named and 1.6 million documented in a central database. These currently living species represent less than one percent of all species that have ever lived on earth.

The earliest evidence of life comes from biogenic carbon signatures and stromatolite fossils discovered in 3.7 billion-year-old metasedimentary rocks from western Greenland. In 2015, possible “remains of biotic life” were found in 4.1 billion-year-old rocks in Western Australia. In March 2017, putative evidence of possibly the oldest forms of life on Earth was reported in the form of fossilized microorganisms discovered in hydrothermal vent precipitates in the Nuvvuagittuq Belt of Quebec, Canada, that may have lived as early as 4.28 billion years ago, not long after the oceans formed 4.4 billion years ago, and not long after the formation of the Earth 4.54 billion years ago.

Microbial mats of coexisting bacteria and archaea were the dominant form of life in the early Archean Epoch and many of the major steps in early evolution are thought to have taken place in this environment. The evolution of photosynthesis, around 3.5 Ga, eventually led to a buildup of its waste product, oxygen, in the atmosphere, leading to the great oxygenation event, beginning around 2.4 Ga. The earliest evidence of eukaryotes (complex cells with organelles) dates from 1.85 Ga, and while they may have been present earlier, their diversification accelerated when they started using oxygen in their metabolism. Later, around 1.7 Ga, multicellular organisms began to appear, with differentiated cells performing specialised functions. Sexual reproduction, which involves the fusion of male and female reproductive cells (gametes) to create a zygote in a process called fertilization is, in contrast to asexual reproduction, the primary method of reproduction for the vast majority of macroscopic organisms, including almost all eukaryotes (which includes animals and plants). However the origin and evolution of sexual reproduction remain a puzzle for biologists though it did evolve from a common ancestor that was a single celled eukaryotic species. Bilateria, animals having a left and a right side that are mirror images of each other, appeared by 555 Ma (million years ago).

The earliest plants on land date back to around 850 million years ago (Ma), from carbon isotopes in Precambrian rocks, while algae-like multicellular land plants are dated back even to about 1 billion years ago, although evidence suggests that microorganisms formed the earliest terrestrial ecosystems, at least 2.7 billion years ago (Ga). Microorganisms are thought to have paved the way for the inception of land plants in the Ordovician. Land plants were so successful that they are thought to have contributed to the Late Devonian extinction event. (The long causal chain implied seems to involve the success of early tree archaeopteris (1) drew down CO2 levels, leading to global cooling and lowered sea levels, (2) roots of archeopteris fostered soil development which increased rock weathering, and the subsequent nutrient run-off may have triggered algal blooms resulting in anoxic events which caused marine-life die-offs. Marine species were the primary victims of the Late Devonian extinction.)

Ediacara biota appear during the Ediacaran period, while vertebrates, along with most other modern phyla originated about 525 Ma during the Cambrian explosion. During the Permian period, synapsids, including the ancestors of mammals, dominated the land, but most of this group became extinct in the Permian–Triassic extinction event 252 Ma. During the recovery from this catastrophe, archosaurs became the most abundant land vertebrates; one archosaur group, the dinosaurs, dominated the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods. After the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event 65 Ma killed off the non-avian dinosaurs, mammals increased rapidly in size and diversity. Such mass extinctions may have accelerated evolution by providing opportunities for new groups of organisms to diversify.

4.3.3 Genetics

Genes are the primary units of inheritance in all organisms. A gene is a unit of heredity and corresponds to a region of DNA that influences the form or function of an organism in specific ways. All organisms, from bacteria to animals, share the same basic machinery that copies and translates DNA into proteins. Cells transcribe a DNA gene into an RNA version of the gene, and a ribosome then translates the RNA into a sequence of amino acids known as a protein. The translation code from RNA codon to amino acid is the same for most organisms. For example, a sequence of DNA that codes for insulin in humans also codes for insulin when inserted into other organisms, such as plants.

DNA is found as linear chromosomes in eukaryotes, and circular chromosomes in prokaryotes. A chromosome is an organized structure consisting of DNA and histones. The set of chromosomes in a cell and any other hereditary information found in the mitochondria, chloroplasts, or other locations is collectively known as a cell’s genome. In eukaryotes, genomic DNA is localized in the cell nucleus, or with small amounts in mitochondria and chloroplasts. In prokaryotes, the DNA is held within an irregularly shaped body in the cytoplasm called the nucleoid. The genetic information in a genome is held within genes, and the complete assemblage of this information in an organism is called its genotype.

4.3.4 Homeostasis

Homeostasis is the ability of an open system to regulate its internal environment to maintain stable conditions by means of multiple dynamic equilibrium adjustments that are controlled by interrelated regulation mechanisms. All living organisms, whether unicellular or multicellular, exhibit homeostasis.

To maintain dynamic equilibrium and effectively carry out certain functions, a system must detect and respond to perturbations. After the detection of a perturbation, a biological system normally responds through negative feedback that stabilize conditions by reducing or increasing the activity of an organ or system. One example is the release of glucagon when sugar levels are too low.

4.3.5 Energy

The survival of a living organism depends on the continuous input of energy. Chemical reactions that are responsible for its structure and function are tuned to extract energy from substances that act as its food and transform them to help form new cells and sustain them. In this process, molecules of chemical substances that constitute food play two roles; first, they contain energy that can be transformed and reused in that organism’s biological, chemical reactions; second, food can be transformed into new molecular structures (biomolecules) that are of use to that organism.

The organisms responsible for the introduction of energy into an ecosystem are known as producers or autotrophs. Nearly all such organisms originally draw their energy from the sun. Plants and other phototrophs use solar energy via a process known as photosynthesis to convert raw materials into organic molecules, such as ATP, whose bonds can be broken to release energy. A few ecosystems, however, depend entirely on energy extracted by chemotrophs from methane, sulfides, or other non-luminal energy sources.

Some of the energy thus captured produces biomass and energy that is available for growth and development of other life forms. The majority of the rest of this biomass and energy are lost as waste molecules and heat. The most important processes for converting the energy trapped in chemical substances into energy useful to sustain life are metabolism and cellular respiration.

Bacteria (singular bacterium) and Archaea (singular archaeon) constitute two domains of single-celled organisms. These microorganisms lack cell nuclei and are therefore prokaryotes.

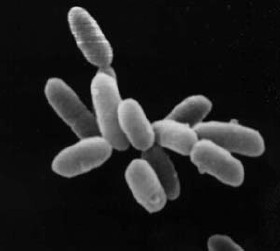

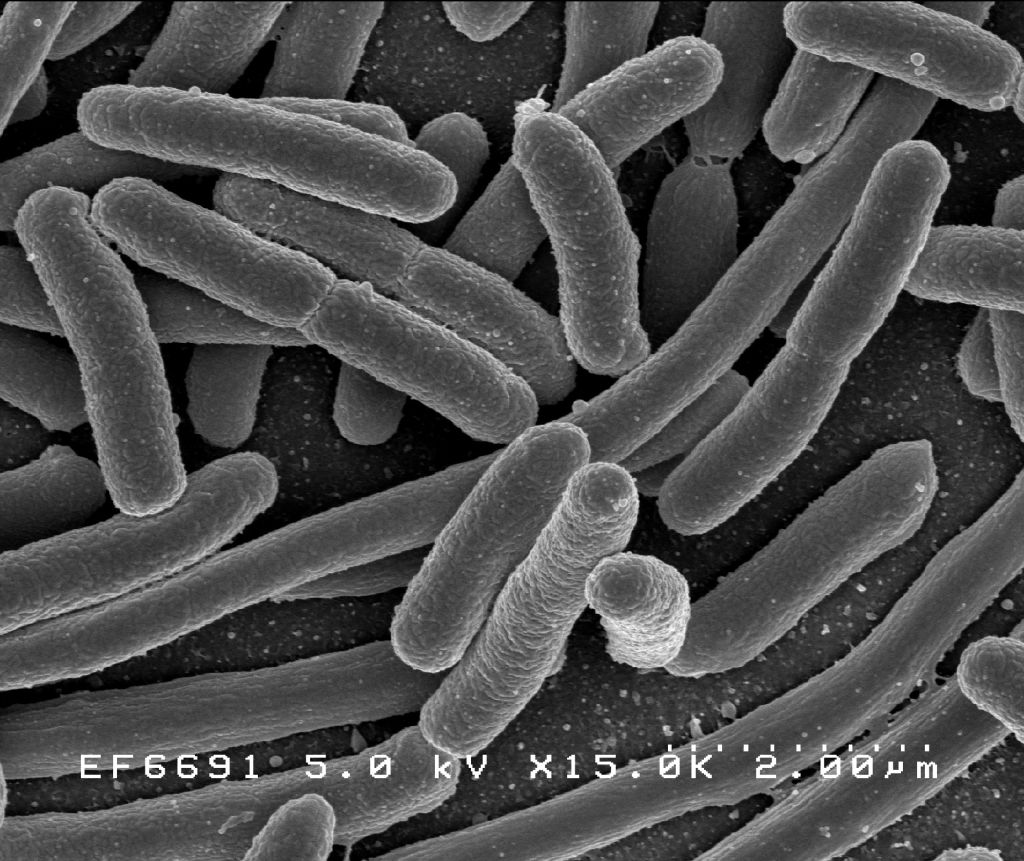

Scanning electron micrograph of Escherichia coli, grown in culture and adhered to a cover slip. Scanning electron micrograph of Escherichia coli bacteria.

Figure 4.5: Scanning electron micrograph of Escherichia coli, grown in culture and adhered to a cover slip.

For much of the 20th century, prokaryotes were regarded as a single group of organisms and classified based on their biochemistry, morphology and metabolism. Microbiologists tried to classify microorganisms based on the structures of their cell walls, their shapes, and the substances they consume. In 1965, Emile Zuckerkandl and Linus Pauling instead proposed using the sequences of the genes in different prokaryotes to work out how they are related to each other. This phylogenetic approach is the main method used today.

Archaea – at that time only the methanogens were known – were first classified separately from bacteria in 1977 by Carl Woese and George E. Fox based on their ribosomal RNA (rRNA) genes. They called these groups the Urkingdoms of Archaebacteria and Eubacteria, though other researchers treated them as kingdoms or subkingdoms. Woese and Fox gave the first evidence for Archaebacteria as a separate “line of descent”: 1. lack of peptidoglycan in their cell walls, 2. two unusual coenzymes, 3. results of 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequencing. To emphasize this difference, Woese, Otto Kandler and Mark Wheelis later proposed reclassifying organisms into three natural domains known as the three-domain system: the Eukarya, the Bacteria and the Archaea, in what is now known as “The Woesian Revolution”.

4.4 Basic Characteristics Of Cells

The cell (from Latin cella, meaning “small room”) is the basic structural, functional, and biological unit of all known organisms. A cell is the smallest unit of life. Cells are often called the “building blocks of life”. The study of cells is called cell biology, cellular biology, or cytology.

Cells consist of cytoplasm enclosed within a membrane, which contains many biomolecules such as proteins and nucleic acids. Most plant and animal cells are only visible under a microscope, with dimensions between 1 and 100 micrometres. Organisms can be classified as unicellular (consisting of a single cell such as bacteria) or multicellular (including plants and animals). Most unicellular organisms are classed as microorganisms.

The number of cell in plants and animals varies from species to species; it has been estimated that humans contain somewhere around 40 trillion (4×1013) cells. The human brain accounts for around 80 billion of these cells.

In biology, cell theory is the historic scientific theory, now universally accepted, that living organisms are made up of cells, that they are the basic structural/organizational unit of all organisms, and that all cells come from pre-existing cells. Cells are the basic unit of structure in all organisms and also the basic unit of reproduction.

Credit for developing cell theory is usually given to two scientists: Theodor Schwann and Matthias Jakob Schleiden. While Rudolf Virchow contributed to the theory, he is not as credited for his attributions toward it. In 1839, Schleiden suggested that every structural part of a plant was made up of cells or the result of cells. He also suggested that cells were made by a crystallization process either within other cells or from the outside. However, this was not an original idea of Schleiden. He claimed this theory as his own, though Barthelemy Dumortier had stated it years before him. This crystallization process is no longer accepted with modern cell theory. In 1839, Theodor Schwann states that along with plants, animals are composed of cells or the product of cells in their structures. This was a major advancement in the field of biology since little was known about animal structure up to this point compared to plants. From these conclusions about plants and animals, two of the three tenets of cell theory were postulated.

- All living organisms are composed of one or more cells

- The cell is the most basic unit of life

Schleiden’s theory of free cell formation through crystallization was refuted in the 1850s by Robert Remak, Rudolf Virchow, and Albert von Kölliker. In 1855, Rudolf Virchow added the third tenet to cell theory. In Latin, this tenet states Omnis cellula e cellula. This translated to:

- All cells arise only from pre-existing cells

However, the idea that all cells come from pre-existing cells had in fact already been proposed by Robert Remak; it has been suggested that Virchow plagiarized Remak and did not give him credit. Remak published observations in 1852 on cell division, claiming Schleiden and Schawnn were incorrect about generation schemes. He instead said that binary fission, which was first introduced by Dumortier, was how reproduction of new animal cells were made. Once this tenet was added, the classical cell theory was complete.

The generally accepted parts of modern cell theory include:

- All living cells arise from pre-existing cells by division.

- The cell is the fundamental unit of structure and function in all living organisms.

- The activity of an organism depends on the total activity of independent cells.

- Energy flow (metabolism and biochemistry) occurs within cells.

- Cells contain DNA which is found specifically in the chromosome and RNA found in the cell nucleus and cytoplasm.

- All cells are basically the same in chemical composition in organisms of similar species.

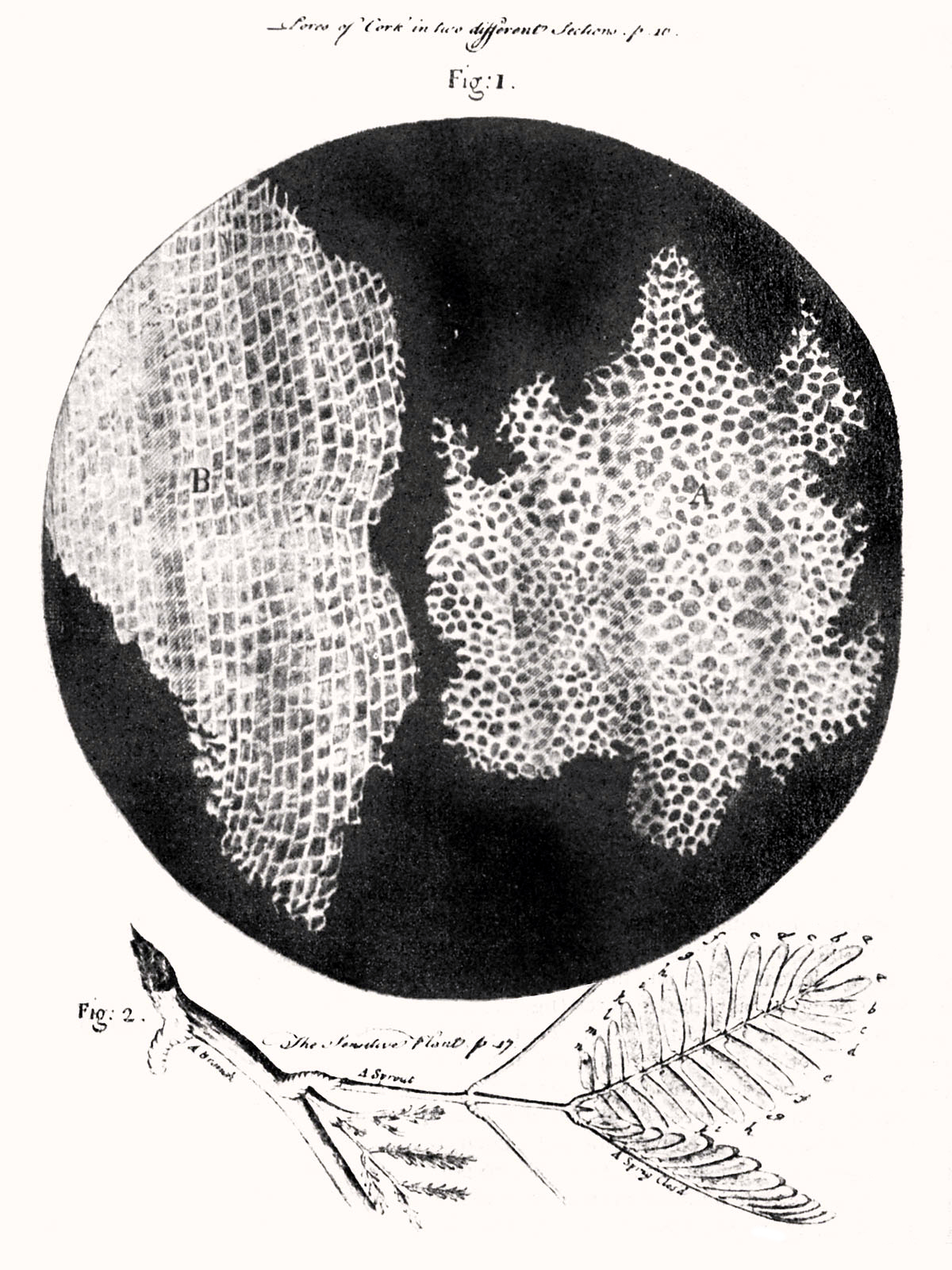

The discovery of the cell was made possible through the invention of the microscope. In the first century BC, Romans were able to make glass, discovering that objects appeared to be larger under the glass. In Italy during the 12th century, Salvino D’Armate made a piece of glass fit over one eye, allowing for a magnification effect to that eye. The expanded use of lenses in eyeglasses in the 13th century probably led to wider spread use of simple microscopes (magnifying glasses) with limited magnification. Compound microscopes, which combine an objective lens with an eyepiece to view a real image achieving much higher magnification, first appeared in Europe around 1620. In 1665, Robert Hooke used a microscope about six inches long with two convex lenses inside and examined specimens under reflected light for the observations in his book Micrographia. Hooke also used a simpler microscope with a single lens for examining specimens with directly transmitted light, because this allowed for a clearer image.

Figure 4.7: Title page of “MICROGRAPHIA or some physiological descriptions of minute bodies made by magnifying glasses with observations and inquiries thereupon”.

Figure 4.9: Hooke was the first to apply the word “cell”to biological objects. Cell structure of cork by Hooke.

Extensive microscopic study was done by Anton van Leeuwenhoek, a draper who took the interest in microscopes after seeing one while on an apprenticeship in Amsterdam in 1648. At some point in his life before 1668, he was able to learn how to grind lenses. This eventually led to Leeuwenhoek making his own unique microscope. His was a single lens simple microscope, rather than a compound microscope. This was because he was able to use a single lens that was a small glass sphere but allowed for a magnification of 270x. This was a large progression since the magnification before was only a maximum of 50x. After Leeuwenhoek, there was not much progress in microscope technology until the 1850s, two hundred years later. Carl Zeiss, a German engineer who manufactured microscopes, began to make changes to the lenses used. But the optical quality did not improve until the 1880s when he hired Otto Schott and eventually Ernst Abbe.

Optical microscopes can focus on objects the size of a wavelength or larger, giving restrictions still to advancement in discoveries with objects smaller than the wavelengths of visible light. The development of the electron microscope in the 1920s made it possible to view objects that are smaller than optical wavelengths, once again opening up new possibilities in science.

The cell was first discovered by Robert Hooke in 1665, which can be found to be described in his book Micrographia. In this book, he gave 60 ‘observations’ in detail of various objects under a coarse, compound microscope. One observation was from very thin slices of bottle cork. Hooke discovered a multitude of tiny pores that he named “cells”. This came from the Latin word Cella, meaning ‘a small room’ like monks lived in and also Cellulae, which meant the six sided cell of a honeycomb. However, Hooke did not know their real structure or function. What Hooke had thought were cells, were actually empty cell walls of plant tissues. With microscopes during this time having a low magnification, Hooke was unable to see that there were other internal components to the cells he was observing. Therefore, he did not think the “cellulae” were alive. His cell observations gave no indication of the nucleus and other organelles found in most living cells. In Micrographia, Hooke also observed mould, bluish in color, found on leather. After studying it under his microscope, he was unable to observe “seeds” that would have indicated how the mould was multiplying in quantity. This led to Hooke suggesting that spontaneous generation, from either natural or artificial heat, was the cause. Since this was an old Aristotelian theory still accepted at the time, others did not reject it and was not disproved until Leeuwenhoek later discovered that generation was achieved otherwise.

Anton van Leeuwenhoek is another scientist who saw these cells soon after Hooke did. He made use of a microscope containing improved lenses that could magnify objects almost 300-fold, or 270x. Under these microscopes, Leeuwenhoek found motile objects. In a letter to The Royal Society on October 9, 1676, he states that motility is a quality of life therefore these were living organisms. Over time, he wrote many more papers in which described many specific forms of microorganisms. Leeuwenhoek named these “animalcules,” which included protozoa and other unicellular organisms, like bacteria. Though he did not have much formal education, he was able to identify the first accurate description of red blood cells and discovered bacteria after gaining interest in the sense of taste that resulted in Leeuwenhoek to observe the tongue of an ox, then leading him to study “pepper water” in 1676. He also found for the first time the sperm cells of animals and humans. Once discovering these types of cells, Leeuwenhoek saw that the fertilization process requires the sperm cell to enter the egg cell. This put an end to the previous theory of spontaneous generation. After reading letters by Leeuwenhoek, Hooke was the first to confirm his observations that were thought to be unlikely by other contemporaries.

The cells in animal tissues were observed after plants were because the tissues were so fragile and susceptible to tearing, it was difficult for such thin slices to be prepared for studying. Biologists believed that there was a fundamental unit to life, but were unsure what this was. It would not be until over a hundred years later that this fundamental unit was connected to cellular structure and existence of cells in animals or plants. This conclusion was not made until Henri Dutrochet. Besides stating “the cell is the fundamental element of organization”, Dutrochet also claimed that cells were not just a structural unit, but also a physiological unit.

In 1804, Karl Rudolphi and Johann Heinrich Friedrich Link were awarded the prize for “solving the problem of the nature of cells”, meaning they were the first to prove that cells had independent cell walls by the Königliche Societät der Wissenschaft (Royal Society of Science), Göttingen. Before, it had been thought that cells shared walls and the fluid passed between them this way.

Cells can be subdivided into the following subcategories:

- Prokaryotes: Prokaryotes are relatively small cells surrounded by the plasma membrane, with a characteristic cell wall that may differ in composition depending on the particular organism. Prokaryotes lack a nucleus (although they do have circular or linear DNA) and other membrane-bound organelles (though they do contain ribosomes). The protoplasm of a prokaryote contains the chromosomal region that appears as fibrous deposits under the microscope, and the cytoplasm. Bacteria and Archaea are the two domains of prokaryotes.

- Eukaryotes: Eukaryotic cells are also surrounded by the plasma membrane, but on the other hand, they have distinct nuclei bound by a nuclear membrane or envelope. Eukaryotic cells also contain membrane-bound organelles, such as (mitochondria, chloroplasts, lysosomes, rough and smooth endoplasmic reticulum, vacuoles). In addition, they possess organized chromosomes which store genetic material. Animals have evolved a greater diversity of cell types in a multicellular body (100–150 different cell types), compared with 10–20 in plants, fungi, and protoctista.

The distinction between prokaryotes and eukaryotes was firmly established by the microbiologists Roger Stanier and C. B. van Niel in their 1962 paper The concept of a bacterium (though spelled procaryote and eucaryote there). That paper cites Édouard Chatton’s 1937 book Titres et Travaux Scientifiques for using those terms and recognizing the distinction. One reason for this classification was so that what was then often called blue-green algae (now called cyanobacteria) would not be classified as plants but grouped with bacteria.

4.5 Prokaryotic Cells

A prokaryote is a cellular organism that lacks an envelope-enclosed nucleus. The word prokaryote comes from the Greek πρό (pro, ‘before’) and κάρυον (karyon, ‘nut’ or ‘kernel’). In the two-empire system arising from the work of Édouard Chatton, prokaryotes were classified within the empire Prokaryota. But in the three-domain system, based upon molecular analysis, prokaryotes are divided into two domains: Bacteria (formerly Eubacteria) and Archaea (formerly Archaebacteria). Organisms with nuclei are placed in a third domain, Eukaryota. In the study of the origins of life, prokaryotes are thought to have arisen before eukaryotes.

Prokaryotes lack mitochondria, or any other eukaryotic membrane-bound organelles; and it was once thought that prokayotes lacked cellular compartments, and therefore all cellular components within the cytoplasm were unenclosed, except for an outer cell membrane. But bacterial microcompartments, which are thought to be primitive organelles enclosed in protein shells, have been discovered; and there is also evidence of prokayotic membrane-bound organelles. While typically being unicellular, some prokaryotes, such as cyanobacteria, may form large colonies. Others, such as myxobacteria, have multicellular stages in their life cycles. Prokaryotes are asexual, reproducing without fusion of gametes, although horizontal gene transfer also takes place.

Figure 4.10: Structure of a typical prokaryotic cell

Molecular studies have provided insight into the evolution and interrelationships of the three domains of life. The division between prokaryotes and eukaryotes reflects the existence of two very different levels of cellular organization; only eukaryotic cells have a enveloped nucleus that contains its chromosomal DNA, and other characteristic membrane-bound organelles including mitochondria. Distinctive types of prokaryotes include extremophiles and methanogens; these are common in some extreme environments.

Prokaryotes include bacteria and archaea, two of the three domains of life. Prokaryotic cells were the first form of life on Earth, characterized by having vital biological processes including cell signaling. They are simpler and smaller than eukaryotic cells, and lack a nucleus, and other membrane-bound organelles. The DNA of a prokaryotic cell consists of a single circular chromosome that is in direct contact with the cytoplasm. The nuclear region in the cytoplas is called the nucleoid. Most prokaryotes are the smallest of all organisms ranging from 0.5 to 2.0 µm in diameter.

A prokaryotic cell has three regions:

- Enclosing the cell is the cell envelope – generally consisting of a plasma membrane covered by a cell wall which, for some bacteria, may be further covered by a third layer called a capsule. Though most prokaryotes have both a cell membrane and a cell wall, there are exceptions such as Mycoplasma (bacteria) and Thermoplasma (archaea) which only possess the cell membrane layer. The envelope gives rigidity to the cell and separates the interior of the cell from its environment, serving as a protective filter. The cell wall consists of peptidoglycan in bacteria, and acts as an additional barrier against exterior forces. It also prevents the cell from expanding and bursting (cytolysis) from osmotic pressure due to a hypotonic environment. Some eukaryotic cells (plant cells and fungal cells) also have a cell wall.

- Inside the cell is the cytoplasmic region that contains the genome (DNA), ribosomes and various sorts of inclusions. The genetic material is freely found in the cytoplasm. Prokaryotes can carry extrachromosomal DNA elements called plasmids, which are usually circular. Linear bacterial plasmids have been identified in several species of spirochete bacteria, including members of the genus Borrelia notably Borrelia burgdorferi, which causes Lyme disease. Though not forming a nucleus, the DNA is condensed in a nucleoid. Plasmids encode additional genes, such as antibiotic resistance genes.

- On the outside, flagella and pili project from the cell’s surface. These are structures (not present in all prokaryotes) made of proteins that facilitate movement and communication between cells.

4.6 Bacteria

Bacteria (plural of the New Latin bacterium, which is the latinisation of the Greek βακτήριον (bakterion), the diminutive of βακτηρία (bakteria), meaning “staff, cane”, because the first ones to be discovered were rod-shaped) constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria have a number of shapes, ranging from spheres to rods and spirals. Bacteria were among the first life forms to appear on Earth, and are present in most of its habitats. Bacteria inhabit soil, water, acidic hot springs, radioactive waste, and the deep biosphere of the earth’s crust. Bacteria also live in symbiotic and parasitic relationships with plants and animals. Most bacteria have not been characterised, and only about 27 percent of the bacterial phyla have species that can be grown in the laboratory. The study of bacteria is known as bacteriology, a branch of microbiology.

Nearly all animal life is dependent on bacteria for survival as only bacteria and some archaea possess the genes and enzymes necessary to synthesize vitamin B12, also known as cobalamin, and provide it through the food chain. Vitamin B12 is a water-soluble vitamin that is involved in the metabolism of every cell of the human body. It is a cofactor in DNA synthesis, and in both fatty acid and amino acid metabolism. It is particularly important in the normal functioning of the nervous system via its role in the synthesis of myelin.

There are typically 40 million bacterial cells in a gram of soil and a million bacterial cells in a millilitre of fresh water. There are approximately 5×1030 bacteria on Earth, forming a biomass which exceeds that of all plants and animals. Bacteria are vital in many stages of the nutrient cycle by recycling nutrients such as the fixation of nitrogen from the atmosphere. The nutrient cycle includes the decomposition of dead bodies; bacteria are responsible for the putrefaction stage in this process. In the biological communities surrounding hydrothermal vents and cold seeps, extremophile bacteria provide the nutrients needed to sustain life by converting dissolved compounds, such as hydrogen sulphide and methane, to energy.

In humans and most animals the largest number of bacteria exist in the gut, and a large number on the skin. The vast majority of the bacteria in the body are rendered harmless by the protective effects of the immune system, though many are beneficial, particularly in the gut flora. However, several species of bacteria are pathogenic and cause infectious diseases, including cholera, syphilis, anthrax, leprosy, and bubonic plague. The most common fatal bacterial diseases are respiratory infections. Tuberculosis alone kills about 2 million people per year, mostly in sub-Saharan Africa. Antibiotics are used to treat bacterial infections and are also used in farming, making antibiotic resistance a growing problem. In industry, bacteria are important in sewage treatment and the breakdown of oil spills, the production of cheese and yogurt through fermentation, the recovery of gold, palladium, copper and other metals in the mining sector, as well as in biotechnology, and the manufacture of antibiotics and other chemicals.

Once regarded as plants constituting the class Schizomycetes (“fission fungi”), bacteria are now classified as prokaryotes. Unlike cells of animals and other eukaryotes, bacterial cells do not contain a nucleus and rarely harbour membrane-bound organelles. Although the term bacteria traditionally included all prokaryotes, the scientific classification changed after the discovery in the 1990s that prokaryotes consist of two very different groups of organisms that evolved from an ancient common ancestor. These evolutionary domains are called Bacteria and Archaea.

The ancestors of modern bacteria were unicellular microorganisms that were the first forms of life to appear on Earth, about 4 billion years ago. For about 3 billion years, most organisms were microscopic, and bacteria and archaea were the dominant forms of life. Although bacterial fossils exist, such as stromatolites, their lack of distinctive morphology prevents them from being used to examine the history of bacterial evolution, or to date the time of origin of a particular bacterial species. However, gene sequences can be used to reconstruct the bacterial phylogeny, and these studies indicate that bacteria diverged first from the archaeal/eukaryotic lineage. The most recent common ancestor of bacteria and archaea was probably a hyperthermophile that lived about 2.5 billion–3.2 billion years ago. The earliest life on land may have been bacteria some 3.22 billion years ago.

Bacteria were also involved in the second great evolutionary divergence, that of the archaea and eukaryotes. Here, eukaryotes resulted from the entering of ancient bacteria into endosymbiotic associations with the ancestors of eukaryotic cells, which were themselves possibly related to the Archaea. This involved the engulfment by proto-eukaryotic cells of alphaproteobacterial symbionts to form either mitochondria or hydrogenosomes, which are still found in all known Eukarya (sometimes in highly reduced form, e.g. in ancient “amitochondrial” protozoa). Later, some eukaryotes that already contained mitochondria also engulfed cyanobacteria-like organisms, leading to the formation of chloroplasts in algae and plants. This is known as primary endosymbiosis.

Bacteria display a wide diversity of shapes and sizes, called morphologies. Bacterial cells are about one-tenth the size of eukaryotic cells and are typically 0.5–5.0 micrometres in length. However, a few species are visible to the unaided eye—for example, Thiomargarita namibiensis is up to half a millimetre long and Epulopiscium fishelsoni reaches 0.7 mm. Among the smallest bacteria are members of the genus Mycoplasma, which measure only 0.3 micrometres, as small as the largest viruses. Some bacteria may be even smaller, but these ultramicrobacteria are not well-studied.

Most bacterial species are either spherical, called cocci (singular coccus, from Greek kókkos, grain, seed), or rod-shaped, called bacilli (sing. bacillus, from Latin baculus, stick). Some bacteria, called vibrio, are shaped like slightly curved rods or comma-shaped; others can be spiral-shaped, called spirilla, or tightly coiled, called spirochaetes. A small number of other unusual shapes have been described, such as star-shaped bacteria. This wide variety of shapes is determined by the bacterial cell wall and cytoskeleton, and is important because it can influence the ability of bacteria to acquire nutrients, attach to surfaces, swim through liquids and escape predators.

Many bacterial species exist simply as single cells, others associate in characteristic patterns: Neisseria form diploids (pairs), Streptococcus form chains, and Staphylococcus group together in “bunch of grapes” clusters. Bacteria can also group to form larger multicellular structures, such as the elongated filaments of Actinobacteria, the aggregates of Myxobacteria, and the complex hyphae of Streptomyces. These multicellular structures are often only seen in certain conditions. For example, when starved of amino acids, Myxobacteria detect surrounding cells in a process known as quorum sensing, migrate towards each other, and aggregate to form fruiting bodies up to 500 micrometres long and containing approximately 100,000 bacterial cells. In these fruiting bodies, the bacteria perform separate tasks; for example, about one in ten cells migrate to the top of a fruiting body and differentiate into a specialised dormant state called a myxospore, which is more resistant to drying and other adverse environmental conditions.

Bacteria often attach to surfaces and form dense aggregations called biofilms, and larger formations known as microbial mats. These biofilms and mats can range from a few micrometres in thickness to up to half a metre in depth, and may contain multiple species of bacteria, protists and archaea. Bacteria living in biofilms display a complex arrangement of cells and extracellular components, forming secondary structures, such as microcolonies, through which there are networks of channels to enable better diffusion of nutrients. In natural environments, such as soil or the surfaces of plants, the majority of bacteria are bound to surfaces in biofilms. Biofilms are also important in medicine, as these structures are often present during chronic bacterial infections or in infections of implanted medical devices, and bacteria protected within biofilms are much harder to kill than individual isolated bacteria.

4.6.1 Intracellular Structure

The bacterial cell is surrounded by a cell membrane, which is made primarily of phospholipids. This membrane encloses the contents of the cell and acts as a barrier to hold nutrients, proteins and other essential components of the cytoplasm within the cell. Unlike eukaryotic cells, bacteria usually lack large membrane-bound structures in their cytoplasm such as a nucleus, mitochondria, chloroplasts and the other organelles present in eukaryotic cells. However, some bacteria have protein-bound organelles in the cytoplasm which compartmentalize aspects of bacterial metabolism, such as the carboxysome. Additionally, bacteria have a multi-component cytoskeleton to control the localisation of proteins and nucleic acids within the cell, and to manage the process of cell division.

Many important biochemical reactions, such as energy generation, occur due to concentration gradients across membranes, creating a potential difference analogous to a battery. The general lack of internal membranes in bacteria means these reactions, such as electron transport, occur across the cell membrane between the cytoplasm and the outside of the cell or periplasm. However, in many photosynthetic bacteria the plasma membrane is highly folded and fills most of the cell with layers of light-gathering membrane. These light-gathering complexes may even form lipid-enclosed structures called chlorosomes in green sulfur bacteria.

Bacteria do not have a membrane-bound nucleus, and their genetic material is typically a single circular bacterial chromosome of DNA located in the cytoplasm in an irregularly shaped body called the nucleoid. The nucleoid contains the chromosome with its associated proteins and RNA. Like all other organisms, bacteria contain ribosomes for the production of proteins, but the structure of the bacterial ribosome is different from that of eukaryotes and Archaea.

Some bacteria produce intracellular nutrient storage granules, such as glycogen, polyphosphate, sulfur or polyhydroxyalkanoates. Bacteria such as the photosynthetic cyanobacteria, produce internal gas vacuoles, which they use to regulate their buoyancy, allowing them to move up or down into water layers with different light intensities and nutrient levels.

4.6.2 Extracellular Structures

Around the outside of the cell membrane is the cell wall. Bacterial cell walls are made of peptidoglycan (also called murein), which is made from polysaccharide chains cross-linked by peptides containing D-amino acids. Bacterial cell walls are different from the cell walls of plants and fungi, which are made of cellulose and chitin, respectively. The cell wall of bacteria is also distinct from that of Archaea, which do not contain peptidoglycan. The cell wall is essential to the survival of many bacteria, and the antibiotic penicillin (produced by a fungus called Penicillium) is able to kill bacteria by inhibiting a step in the synthesis of peptidoglycan.

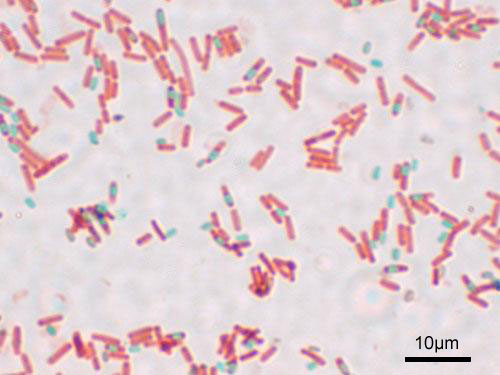

There are broadly speaking two different types of cell wall in bacteria, that classify bacteria into Gram-positive bacteria and Gram-negative bacteria. The names originate from the reaction of cells to the Gram stain, a long-standing test for the classification of bacterial species.

Gram-positive bacteria possess a thick cell wall containing many layers of peptidoglycan and teichoic acids. In contrast, Gram-negative bacteria have a relatively thin cell wall consisting of a few layers of peptidoglycan surrounded by a second lipid membrane containing lipopolysaccharides and lipoproteins. Most bacteria have the Gram-negative cell wall, and only the Firmicutes and Actinobacteria (previously known as the low G+C and high G+C Gram-positive bacteria, respectively) have the alternative Gram-positive arrangement. These differences in structure can produce differences in antibiotic susceptibility; for instance, vancomycin can kill only Gram-positive bacteria and is ineffective against Gram-negative pathogens, such as Haemophilus influenzae or Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Some bacteria have cell wall structures that are neither classically Gram-positive or Gram-negative. This includes clinically important bacteria such as Mycobacteria which have a thick peptidoglycan cell wall like a Gram-positive bacterium, but also a second outer layer of lipids.

In many bacteria, an S-layer of rigidly arrayed protein molecules covers the outside of the cell. This layer provides chemical and physical protection for the cell surface and can act as a macromolecular diffusion barrier. S-layers have diverse but mostly poorly understood functions, but are known to act as virulence factors in Campylobacter and contain surface enzymes in Bacillus stearothermophilus.

Figure 4.12: Helicobacter pylori electron micrograph, showing multiple flagella on the cell surface

Flagella are rigid protein structures, about 20 nanometres in diameter and up to 20 micrometres in length, that are used for motility. Flagella are driven by the energy released by the transfer of ions down an electrochemical gradient across the cell membrane.

The bacterial flagellum is made up of the protein flagellin. Its shape is a 20-nanometer-thick hollow tube. It is helical and has a sharp bend just outside the outer membrane; this “hook” allows the axis of the helix to point directly away from the cell. A shaft runs between the hook and the basal body, passing through protein rings in the cell’s membrane that act as bearings. Gram-positive organisms have two of these basal body rings, one in the peptidoglycan layer and one in the plasma membrane. Gram-negative organisms have four such rings: the L ring associates with the lipopolysaccharides, the P ring associates with peptidoglycan layer, the M ring is embedded in the plasma membrane, and the S ring is directly attached to the plasma membrane. The filament ends with a capping protein.

Figure 4.13: Gram-negative bacterial flagellum. A flagellum is a long, slender projection from the cell body, whose function is to propel a unicellular or small multicellular organism. The depicted type of flagellum is found in bacteria such as E. coli and Salmonella, and rotates like a propeller when the bacterium swims. The bacterial movement can be divided into 2 kinds: run, resulting from a counterclockwise rotation of the flagellum, and tumbling, from a clockwise rotation of the flagellum.

The flagellar filament is the long, helical screw that propels the bacterium when rotated by the motor, through the hook. In most bacteria that have been studied, including the Gram-negative Escherichia coli, Salmonella typhimurium, Caulobacter crescentus, and Vibrio alginolyticus, the filament is made up of 11 protofilaments approximately parallel to the filament axis. Each protofilament is a series of tandem protein chains. However, Campylobacter jejuni has seven protofilaments.

The basal body has several traits in common with some types of secretory pores, such as the hollow, rod-like “plug” in their centers extending out through the plasma membrane. The similarities between bacterial flagella and bacterial secretory system structures and proteins provide scientific evidence supporting the theory that bacterial flagella evolved from the type-three secretion system.

The bacterial flagellum is driven by a rotary engine (Mot complex) made up of protein, located at the flagellum’s anchor point on the inner cell membrane. The engine is powered by proton motive force, i.e., by the flow of protons (hydrogen ions) across the bacterial cell membrane due to a concentration gradient set up by the cell’s metabolism (Vibrio species have two kinds of flagella, lateral and polar, and some are driven by a sodium ion pump rather than a proton pump). The rotor transports protons across the membrane, and is turned in the process. The rotor alone can operate at 6,000 to 17,000 rpm, but with the flagellar filament attached usually only reaches 200 to 1000 rpm. The direction of rotation can be changed by the flagellar motor switch almost instantaneously, caused by a slight change in the position of a protein, FliG, in the rotor. The flagellum is highly energy efficient and uses very little energy.[unreliable source?] The exact mechanism for torque generation is still poorly understood. Because the flagellar motor has no on-off switch, the protein epsE is used as a mechanical clutch to disengage the motor from the rotor, thus stopping the flagellum and allowing the bacterium to remain in one place.

The cylindrical shape of flagella is suited to locomotion of microscopic organisms; these organisms operate at a low Reynolds number, where the viscosity of the surrounding water is much more important than its mass or inertia.

The rotational speed of flagella varies in response to the intensity of the proton motive force, thereby permitting certain forms of speed control, and also permitting some types of bacteria to attain remarkable speeds in proportion to their size; some achieve roughly 60 cell lengths per second. At such a speed, a bacterium would take about 245 days to cover 1 km; although that may seem slow, the perspective changes when the concept of scale is introduced. In comparison to macroscopic life forms, it is very fast indeed when expressed in terms of number of body lengths per second. A cheetah, for example, only achieves about 25 body lengths per second.

Through use of their flagella, E. coli is able to move rapidly towards attractants and away from repellents, by means of a biased random walk, with ‘runs’ and ‘tumbles’ brought about by rotating its flagellum counterclockwise and clockwise, respectively. The two directions of rotation are not identical (with respect to flagellum movement) and are selected by a molecular switch.

During flagellar assembly, components of the flagellum pass through the hollow cores of the basal body and the nascent filament. During assembly, protein components are added at the flagellar tip rather than at the base. In vitro, flagellar filaments assemble spontaneously in a solution containing purified flagellin as the sole protein.

At least 10 protein components of the bacterial flagellum share homologous proteins with the type three secretion system (T3SS) found in many gram-negative bacteria, hence one likely evolved from the other. Because the T3SS has a similar number of components as a flagellar apparatus (about 25 proteins), which one evolved first is difficult to determine. However, the flagellar system appears to involve more proteins overall, including various regulators and chaperones, hence it has been argued that flagella evolved from a T3SS. However, it has also been suggested that the flagellum may have evolved first or the two structures evolved in parallel. Early single-cell organisms’ need for motility (mobility) support that the more mobile flagella would be selected by evolution first, but the T3SS evolving from the flagellum can be seen as ‘reductive evolution’, and receives no topological support from the phylogenetic trees. The hypothesis that the two structures evolved separately from a common ancestor accounts for the protein similarities between the two structures, as well as their functional diversity.

Different species of bacteria have different numbers and arrangements of flagella.

- Monotrichous bacteria have a single flagellum (e.g., Vibrio cholerae).

- Lophotrichous bacteria have multiple flagella located at the same spot on the bacterial surfaces which act in concert to drive the bacteria in a single direction. In many cases, the bases of multiple flagella are surrounded by a specialized region of the cell membrane, called the polar organelle.[citation needed]

- Amphitrichous bacteria have a single flagellum on each of two opposite ends (only one flagellum operates at a time, allowing the bacterium to reverse course rapidly by switching which flagellum is active).

- Peritrichous bacteria have flagella projecting in all directions (e.g., E. coli).

In certain large forms of Selenomonas, more than 30 individual flagella are organized outside the cell body, helically twining about each other to form a thick structure (easily visible with the light microscope) called a “fascicle”.

Spirochetes, in contrast, have flagella called endoflagella arising from opposite poles of the cell, and are located within the periplasmic space as shown by breaking the outer-membrane and also by electron cryotomography microscopy. The rotation of the filaments relative to the cell body causes the entire bacterium to move forward in a corkscrew-like motion, even through material viscous enough to prevent the passage of normally flagellated bacteria.

Counterclockwise rotation of a monotrichous polar flagellum pushes the cell forward with the flagellum trailing behind, much like a corkscrew moving inside cork. Indeed, water on the microscopic scale is highly viscous, very different from our daily experience of water.

Flagella are left-handed helices, and bundle and rotate together only when rotating counterclockwise. When some of the rotors reverse direction, the flagella unwind and the cell starts “tumbling”. Even if all flagella would rotate clockwise, they likely will not form a bundle, due to geometrical, as well as hydrodynamic reasons. Such “tumbling” may happen occasionally, leading to the cell seemingly thrashing about in place, resulting in the reorientation of the cell. The clockwise rotation of a flagellum is suppressed by chemical compounds favorable to the cell (e.g. food), but the motor is highly adaptive to this. Therefore, when moving in a favorable direction, the concentration of the chemical attractant increases and “tumbles” are continually suppressed; however, when the cell’s direction of motion is unfavorable (e.g., away from a chemical attractant), tumbles are no longer suppressed and occur much more often, with the chance that the cell will be thus reoriented in the correct direction.

In some Vibrio spp. (particularly Vibrio parahaemolyticus) and related proteobacteria such as Aeromonas, two flagellar systems co-exist, using different sets of genes and different ion gradients for energy. The polar flagella are constitutively expressed and provide motility in bulk fluid, while the lateral flagella are expressed when the polar flagella meet too much resistance to turn. These provide swarming motility on surfaces or in viscous fluids.

Fimbriae (sometimes called “attachment pili”) are fine filaments of protein, usually 2–10 nanometres in diameter and up to several micrometres in length. They are distributed over the surface of the cell, and resemble fine hairs when seen under the electron microscope. Fimbriae are believed to be involved in attachment to solid surfaces or to other cells, and are essential for the virulence of some bacterial pathogens. Pili (sing. pilus) are cellular appendages, slightly larger than fimbriae, that can transfer genetic material between bacterial cells in a process called conjugation where they are called conjugation pili or sex pili (see bacterial genetics, below). They can also generate movement where they are called type IV pili.

Glycocalyx is produced by many bacteria to surround their cells, and varies in structural complexity: ranging from a disorganised slime layer of extracellular polymeric substances to a highly structured capsule. These structures can protect cells from engulfment by eukaryotic cells such as macrophages (part of the human immune system). They can also act as antigens and be involved in cell recognition, as well as aiding attachment to surfaces and the formation of biofilms.

The assembly of these extracellular structures is dependent on bacterial secretion systems. These transfer proteins from the cytoplasm into the periplasm or into the environment around the cell. Many types of secretion systems are known and these structures are often essential for the virulence of pathogens, so are intensively studied.

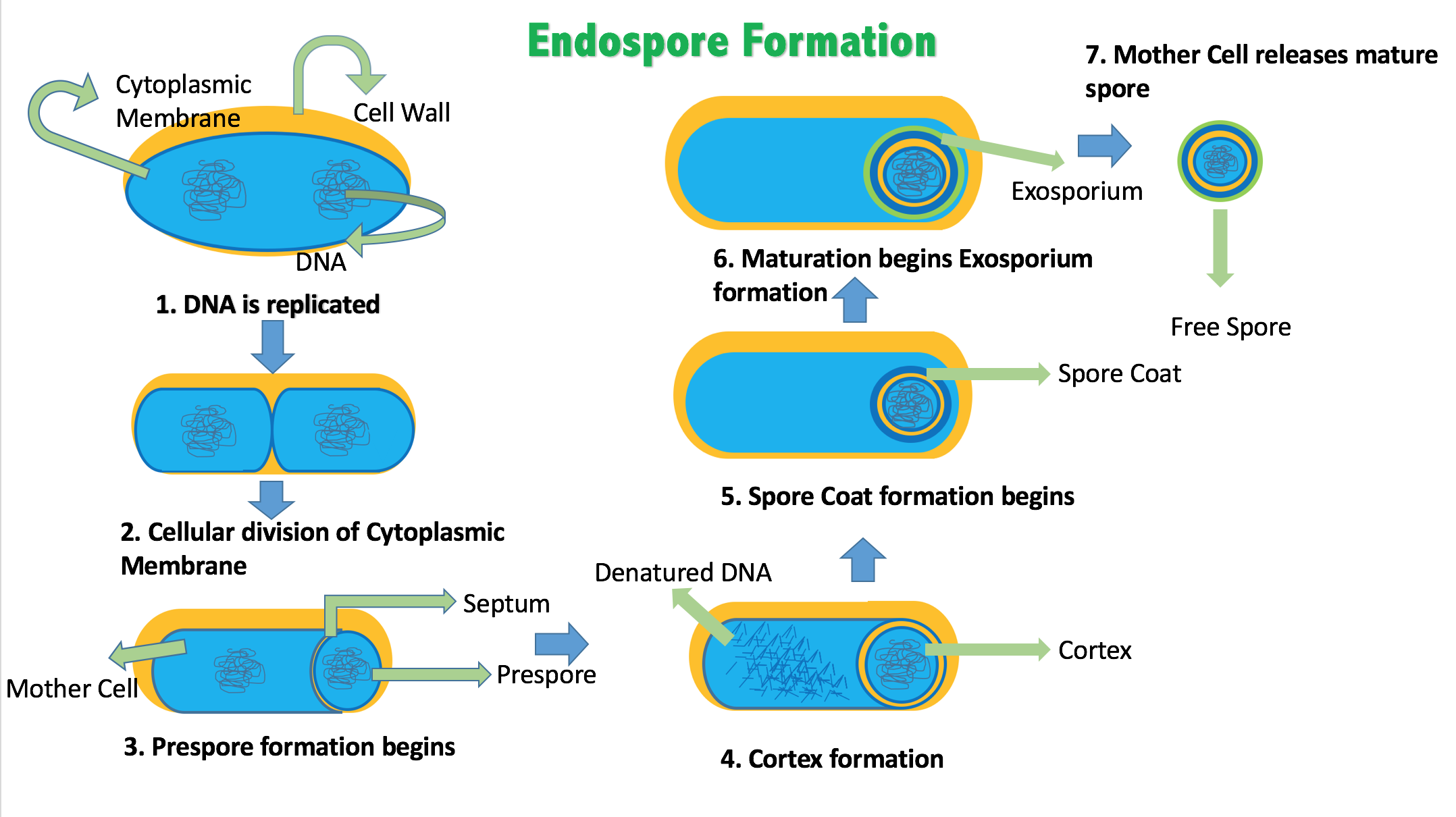

4.6.3 Endospores

Certain genera of Gram-positive bacteria, such as Bacillus, Clostridium, Sporohalobacter, Anaerobacter, and Heliobacterium, can form highly resistant, dormant structures called endospores. Endospores develop within the cytoplasm of the cell; generally a single endospore develops in each cell. Each endospore contains a core of DNA and ribosomes surrounded by a cortex layer and protected by a multilayer rigid coat composed of peptidoglycan and a variety of proteins.

Figure 4.14: A stained preparation of the cell Bacillus subtilis showing endospores as green and the vegetative cell as red.

Endospores show no detectable metabolism and can survive extreme physical and chemical stresses, such as high levels of UV light, gamma radiation, detergents, disinfectants, heat, freezing, pressure, and desiccation. In this dormant state, these organisms may remain viable for millions of years, and endospores even allow bacteria to survive exposure to the vacuum and radiation in space, possibly bacteria could be distributed throughout the Universe by space dust, meteoroids, asteroids, comets, planetoids or via directed panspermia. Endospore-forming bacteria can also cause disease: for example, anthrax can be contracted by the inhalation of Bacillus anthracis endospores, and contamination of deep puncture wounds with Clostridium tetani endospores causes tetanus.

4.6.4 Metabolism

Bacteria exhibit an extremely wide variety of metabolic types. The distribution of metabolic traits within a group of bacteria has traditionally been used to define their taxonomy, but these traits often do not correspond with modern genetic classifications. Bacterial metabolism is classified into nutritional groups on the basis of three major criteria: the source of energy, the electron donors used, and the source of carbon used for growth.

Bacteria either derive energy from light using photosynthesis (called phototrophy), or by breaking down chemical compounds using oxidation (called chemotrophy). Chemotrophs use chemical compounds as a source of energy by transferring electrons from a given electron donor to a terminal electron acceptor in a redox reaction. This reaction releases energy that can be used to drive metabolism. Chemotrophs are further divided by the types of compounds they use to transfer electrons. Bacteria that use inorganic compounds such as hydrogen, carbon monoxide, or ammonia as sources of electrons are called lithotrophs, while those that use organic compounds are called organotrophs. The compounds used to receive electrons are also used to classify bacteria: aerobic organisms use oxygen as the terminal electron acceptor, while anaerobic organisms use other compounds such as nitrate, sulfate, or carbon dioxide.

Many bacteria get their carbon from other organic carbon, called heterotrophy. Others such as cyanobacteria and some purple bacteria are autotrophic, meaning that they obtain cellular carbon by fixing carbon dioxide. In unusual circumstances, the gas methane can be used by methanotrophic bacteria as both a source of electrons and a substrate for carbon anabolism.

| Nutritional Type | Source of Energy | Source of Carbon | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|