9 Microbial Genetics

9.1 Introduction To Genetics And Genes

Genetics is a branch of biology concerned with the study of genes, genetic variation, and heredity in organisms.

The word genetics stems from the ancient Greek γενετικός genetikos meaning “genitive”/“generative”, which in turn derives from γένεσις genesis meaning “origin”.

Though heredity had been observed for millennia, Gregor Mendel, a scientist and Augustinian friar working in the 19th century, was the first to study genetics scientifically. Mendel studied “trait inheritance”, patterns in the way traits are handed down from parents to offspring. He observed that organisms (pea plants) inherit traits by way of discrete “units of inheritance”. This term, still used today, is a somewhat ambiguous definition of what is referred to as a gene. Mendel’s conclusions were largely ignored by the vast majority of scientists at the time. In 1900, however, his work was “re-discovered” by three European scientists, Hugo de Vries, Carl Correns, and Erich von Tschermak. In 1905, Wilhelm Johannsen introduced the term gene and William Bateson the term genetics (the adjective genetic predates the noun and was first used in a biological sense in 1860). Our understanding of what a gene is has undergone quite a bit of change. Currently, genes are considered to be pieces of DNA that contain information for synthesis of ribonuclec acids (RNAs) that can be directly functional or serve as the intermediate template for a protein that performs a function.

Trait inheritance and molecular inheritance mechanisms of genes are still primary principles of genetics in the 21st century, but modern genetics has expanded beyond inheritance to studying the function and behavior of genes. Gene structure and function, variation, and distribution are studied within the context of the cell, the organism (e.g. dominance), and within the context of a population. Genetics has given rise to a number of subfields, including molecular genetics, epigenetics and population genetics. Organisms studied within the broad field span the three domains of life (archaea, bacteria, and eukarya).

Genetic processes work in combination with an organism’s environment and experiences to influence development and behavior, often referred to as nature versus nurture. The intracellular or extracellular environment of a living cell or organism may switch gene transcription on or off. A classic example is two seeds of genetically identical corn, one placed in a temperate climate and one in an arid climate (lacking sufficient waterfall or rain). While the average height of the two corn stalks may be genetically determined to be equal, the one in the arid climate only grows to half the height of the one in the temperate climate due to lack of water and nutrients in its environment.

The observation that living things inherit traits from their parents has been used since prehistoric times to improve crop plants and animals through selective breeding. The modern science of genetics, seeking to understand this process, is generally considered to have began with the work of the Augustinian friar Gregor Mendel in the mid-19th century.

Other theories of inheritance preceded Mendel’s work. A popular theory during the 19th century, and implied by Charles Darwin’s 1859 On the Origin of Species, was blending inheritance: the idea that individuals inherit a smooth blend of traits from their parents. Mendel’s work provided examples where traits were definitely not blended after hybridization, showing that traits are produced by combinations of distinct genes rather than a continuous blend. Blending of traits in the progeny is now explained by the action of multiple genes with quantitative effects. Another theory that had some support at that time was the inheritance of acquired characteristics: the belief that individuals inherit traits strengthened by their parents. This theory (commonly associated with Jean-Baptiste Lamarck) is now known to be wrong—the experiences of individuals do not affect the genes they pass to their children, although evidence in the field of epigenetics has revived some aspects of Lamarck’s theory. Other theories included the pangenesis of Charles Darwin (which had both acquired and inherited aspects) and Francis Galton’s reformulation of pangenesis as both particulate and inherited.

9.1.1 Mendelian (Classical) Genetics

Modern genetics started with Mendel’s studies of the nature of inheritance in plants. In his paper “Versuche über Pflanzenhybriden” (“Experiments on Plant Hybridization”), presented in 1865 to the Naturforschender Verein (Society for Research in Nature) in Brünn, Mendel traced the inheritance patterns of certain traits in pea plants and described them mathematically. Although this pattern of inheritance could only be observed for a few traits, Mendel’s work suggested that heredity was particulate, not acquired, and that the inheritance patterns of many traits could be explained through simple rules and ratios.

The importance of Mendel’s work did not gain wide understanding until 1900, after his death, when Hugo de Vries and other scientists rediscovered his research. William Bateson, a proponent of Mendel’s work, coined the word genetics in 1905 . Bateson both acted as a mentor and was aided significantly by the work of other scientists from Newnham College at Cambridge, specifically the work of Becky Saunders, Nora Darwin Barlow, and Muriel Wheldale Onslow. Bateson popularized the usage of the word genetics to describe the study of inheritance in his inaugural address to the Third International Conference on Plant Hybridization in London in 1906.

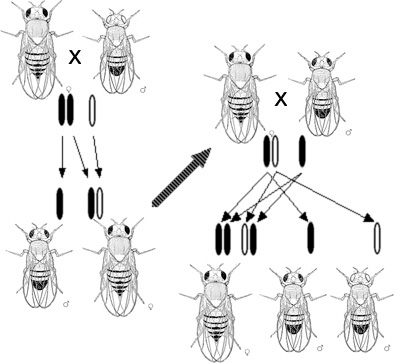

After the rediscovery of Mendel’s work, scientists tried to determine which molecules in the cell were responsible for inheritance. In 1911, Thomas Hunt Morgan argued that genes are on chromosomes, based on observations of a sex-linked white eye mutation in fruit flies. In 1913, his student Alfred Sturtevant used the phenomenon of genetic linkage to show that genes are arranged linearly on the chromosome.

9.1.2 Molecular Genetics

In an influential published in 1941 paper, George Beadle and Edward Tatum proposed the idea that genes act through the production of enzymes, with each gene responsible for producing a single enzyme that in turn affects a single step in a metabolic pathway. The concept arose from work on genetic mutations in the mold Neurospora crassa, and subsequently was dubbed the “one gene–one enzyme hypothesis” by their collaborator Norman Horowitz. In 2004 Norman Horowitz reminisced that “these experiments founded the science of what Beadle and Tatum called ‘biochemical genetics.’ These experiments are by some considered to constitute the begining of what became molecular genetics and the development of the one gene–one enzyme hypothesis is often considered the first significant result in what came to be called molecular biology. Although it has been extremely influential, the hypothesis was recognized soon after its proposal to be an oversimplification. Even the subsequent reformulation of the”one gene–one polypeptide" hypothesis is now considered too simple to describe the relationship between genes and proteins. In attributing an instructional role to genes, Beadle and Tatum implicitly accorded genes an informational capability. This insight provided the foundation for the concept of a genetic code. However, it was not until the experiments were performed showing that DNA was the genetic material, that proteins consist of a defined linear sequence of amino acids, and that DNA structure contained a linear sequence of base pairs, was there a clear basis for solving the genetic code.

In attributing an instructional role to genes, Beadle and Tatum implicitly accorded genes an informational capability. This insight provided the foundation for the concept of a genetic code. However, it was not until the experiments were performed showing that DNA was the genetic material, that proteins consist of a defined linear sequence of amino acids, and that DNA structure contained a linear sequence of base pairs, was there a clear basis for solving the genetic code.

Although genes were known to exist on chromosomes, chromosomes are composed of both protein and DNA, and scientists did not know which of the two is responsible for inheritance. In 1928, Frederick Griffith discovered the phenomenon of transformation: dead bacteria could transfer genetic material to “transform” other still-living bacteria. Sixteen years later, in 1944, the Avery–MacLeod–McCarty experiment identified DNA as the molecule responsible for transformation. The role of the nucleus as the repository of genetic information in eukaryotes had been established by Hämmerling in 1943 in his work on the single celled alga Acetabularia. The Hershey–Chase experiment in 1952 confirmed that DNA (rather than protein) is the genetic material of the viruses that infect bacteria, providing further evidence that DNA is the molecule responsible for inheritance.

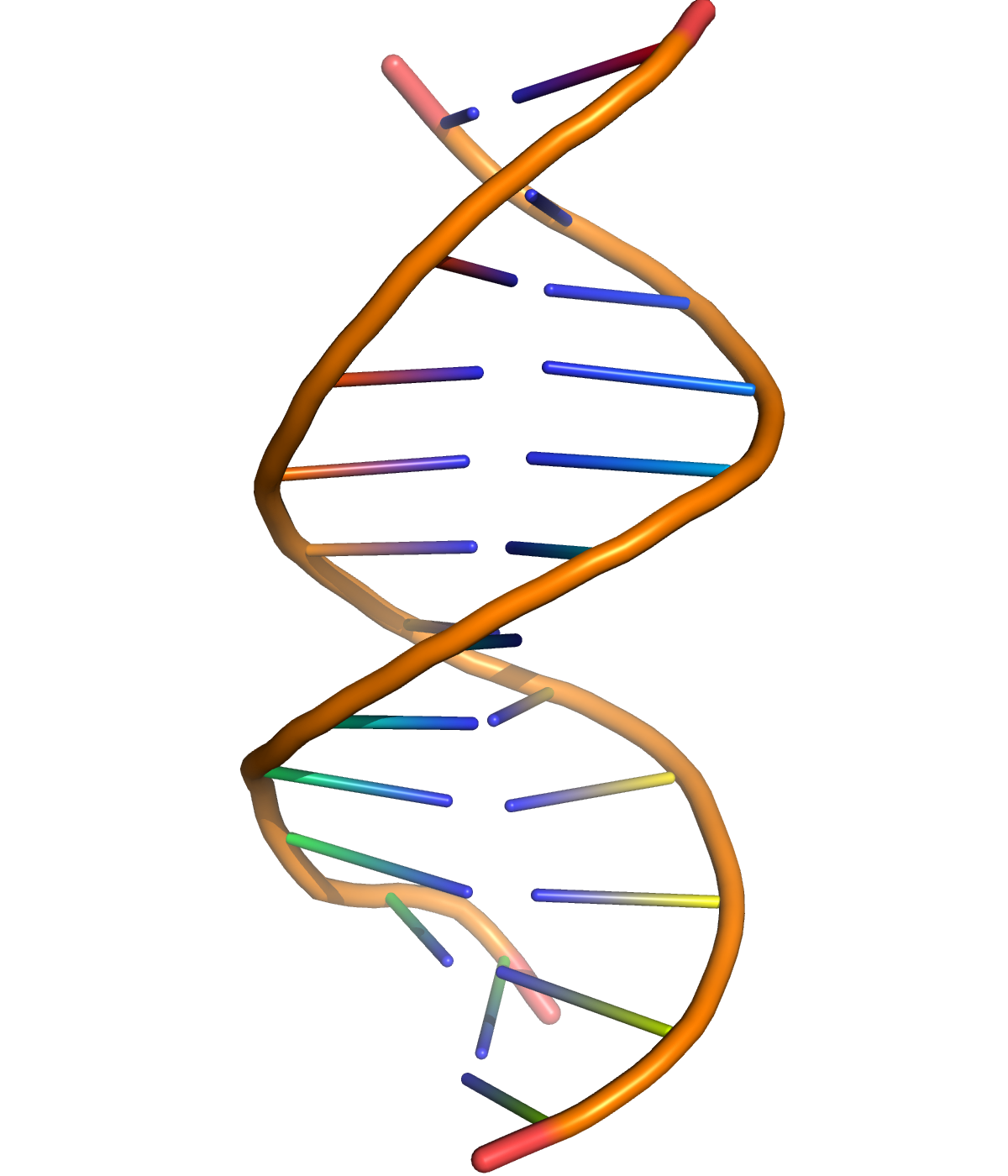

James Watson and Francis Crick determined the structure of DNA in 1953, using the X-ray crystallography work of Rosalind Franklin and Maurice Wilkins that indicated DNA has a helical structure (i.e., shaped like a corkscrew). Their double-helix model had two strands of DNA with the nucleotides pointing inward, each matching a complementary nucleotide on the other strand to form what look like rungs on a twisted ladder. This structure showed that genetic information exists in the sequence of nucleotides on each strand of DNA. The structure also suggested a simple method for replication: if the strands are separated, new partner strands can be reconstructed for each based on the sequence of the old strand. This property is what gives DNA its semi-conservative nature where one strand of new DNA is from an original parent strand.

Figure 9.2: A cartoon representation of DNA based on atomic coordinates of PDB 1BNA, rendered with open source molecular visualization tool PyMol.

Although the structure of DNA showed how inheritance works, it was still not known how DNA influences the behavior of cells. In the following years, scientists tried to understand how DNA controls the process of protein production. It was discovered that the cell uses DNA as a template to create matching messenger RNA, molecules with nucleotides very similar to DNA. The nucleotide sequence of a messenger RNA is used as a template by ribosomes to create an amino acid sequence in protein; this correspondence between nucleotide sequences and amino acid sequences is known as the genetic code.

With the newfound molecular understanding of inheritance came an explosion of research. One important development was chain-termination DNA sequencing in 1977 by Frederick Sanger. This technology allows scientists to read the nucleotide sequence of a DNA molecule. In 1983, Kary Banks Mullis developed the polymerase chain reaction, providing a quick way to isolate and amplify a specific section of DNA from a mixture. The efforts of the Human Genome Project, Department of Energy, NIH, and parallel private efforts by Celera Genomics led to the sequencing of the human genome in 2003.

9.2 The Genetic Code

Whereas other aspects such as the 3D structure, called tertiary structure, of protein can only be predicted using sophisticated algorithms, the amino acid sequence, called primary structure, can be determined solely from the nucleic acid sequence with the aid of a translation table.

| U | C | A | G | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U | UUU Phenylalanine (Phe) | UCU Serine (Ser) | UAU Tyrosine (Tyr) | UGU Cysteine (Cys) | U |

| U | UUC Phe | UCC Ser | UAC Tyr | UGC Cys | C |

| U | UUA Leucine (Leu) | UCA Ser | UAA STOP | UGA STOP | A |

| U | UUG Leu | UCG Ser | UAG STOP | UGG Tryptophan (Trp) | G |

| C | CUU Leucine (Leu) | CCU Proline (Pro) | CAU Histidine (His) | CGU Arginine (Arg) | U |

| C | CUC Leu | CCC Pro | CAC His | CGC Arg | C |

| C | CUA Leu | CCA Pro | CAA Glutamine (Gln) | CGA Arg | A |

| C | CUG Leu | CCG Pro | CAG Gln | CGG Arg | G |

| A | AUU Isoleucine (Ile) | ACU Threonine (Thr) | AAU Asparagine (Asn) | AGU Serine (Ser) | U |

| A | AUC Ile | ACC Thr | AAC Asn | AGC Ser | C |

| A | AUA Ile | ACA Thr | AAA Lysine (Lys) | AGA Arginine (Arg) | A |

| A | AUG Methionine (Met) or START | ACG Thr | AAG Lys | AGG Arg | G |

| G | GUU Valine Val | GCU Alanine (Ala) | GAU Aspartic acid (Asp) | GGU Glycine (Gly) | U |

| G | GUC (Val) | GCC Ala | GAC Asp | GGC Gly | C |

| G | GUA Val | GCA Ala | GAA Glutamic acid (Glu) | GGA Gly | A |

| G | GUG Val | GCG Ala | GAG Glu | GGG Gly | G |

There are many computer programs capable of translating a DNA/RNA sequence into a protein sequence. Normally this is performed using the Standard Genetic Code (Table 9.1), however, few programs can handle all the “special” cases, such as the use of the alternative initiation codons. For instance, the rare alternative start codon CTG codes for Methionine when used as a start codon, and for Leucine in all other positions.

9.2.1 Gene Expression

Genes generally express their functional effect through the production of proteins, which are complex molecules responsible for most functions in the cell. Proteins are made up of one or more polypeptide chains, each of which is composed of a sequence of amino acids, and the DNA sequence of a gene encodes the amino acid sequence of the corresponding protein. This process begins with the production of a messenger RNA (mRNA) molecule with a sequence matching the gene’s DNA sequence, a process called transcription.

This messenger RNA molecule is then used to produce a corresponding amino acid sequence through a process called translation. Each group of three nucleotides in the sequence, called a codon, corresponds either to one of the twenty possible amino acids in a protein or an instruction to end the amino acid sequence; this correspondence is called the genetic code. The flow of information is unidirectional: information is transferred from nucleotide sequences into the amino acid sequence of proteins, but it never transfers from protein back into the sequence of DNA—a phenomenon Francis Crick called the central dogma of molecular biology.

The specific sequence of amino acids results in a unique three-dimensional structure for that protein, and the three-dimensional structures of proteins are related to their functions. Some are simple structural molecules, like the fibers formed by the protein collagen. Proteins can bind to other proteins and simple molecules, sometimes acting as enzymes by facilitating chemical reactions within the bound molecules (without changing the structure of the protein itself). Protein structure is dynamic; the protein hemoglobin bends into slightly different forms as it facilitates the capture, transport, and release of oxygen molecules within mammalian blood.

A single nucleotide difference within DNA can cause a change in the amino acid sequence of a protein. Because protein structures are the result of their amino acid sequences, some changes can dramatically change the properties of a protein by destabilizing the structure or changing the surface of the protein in a way that changes its interaction with other proteins and molecules. For example, sickle-cell anemia is a human genetic disease that results from a single base difference within the coding region for the β-globin section of hemoglobin, causing a single amino acid change that changes hemoglobin’s physical properties. Sickle-cell versions of hemoglobin stick to themselves, stacking to form fibers that distort the shape of red blood cells carrying the protein. These sickle-shaped cells no longer flow smoothly through blood vessels, having a tendency to clog or degrade, causing the medical problems associated with this disease.

Some DNA sequences are transcribed into RNA but are not translated into protein products—such RNA molecules are called non-coding RNA. In some cases, these products fold into structures which are involved in critical cell functions (e.g. ribosomal RNA and transfer RNA). RNA can also have regulatory effects through hybridization interactions with other RNA molecules (e.g. microRNA).

9.2.2 Nature And Nurture

Although genes contain all the information an organism uses to function, the environment plays an important role in determining the ultimate phenotypes an organism displays. The phrase “nature and nurture” refers to this complementary relationship. The phenotype of an organism depends on the interaction of genes and the environment. An interesting example is the coat coloration of the Siamese cat. In this case, the body temperature of the cat plays the role of the environment. The cat’s genes code for dark hair, thus the hair-producing cells in the cat make cellular proteins resulting in dark hair. But these dark hair-producing proteins are sensitive to temperature (i.e. have a mutation causing temperature-sensitivity) and denature in higher-temperature environments, failing to produce dark-hair pigment in areas where the cat has a higher body temperature. In a low-temperature environment, however, the protein’s structure is stable and produces dark-hair pigment normally. The protein remains functional in areas of skin that are colder—such as its legs, ears, tail and face—so the cat has dark hair at its extremities.

Environment plays a major role in effects of the human genetic disease phenylketonuria. The mutation that causes phenylketonuria disrupts the ability of the body to break down the amino acid phenylalanine, causing a toxic build-up of an intermediate molecule that, in turn, causes severe symptoms of progressive intellectual disability and seizures. However, if someone with the phenylketonuria mutation follows a strict diet that avoids this amino acid, they remain normal and healthy.

A common method for determining how genes and environment (“nature and nurture”) contribute to a phenotype involves studying identical and fraternal twins, or other siblings of multiple births. Identical siblings are genetically the same since they come from the same zygote. Meanwhile, fraternal twins are as genetically different from one another as normal siblings. By comparing how often a certain disorder occurs in a pair of identical twins to how often it occurs in a pair of fraternal twins, scientists can determine whether that disorder is caused by genetic or postnatal environmental factors. However, such tests cannot separate genetic factors from environmental factors affecting fetal development.

9.2.3 Gene Regulation

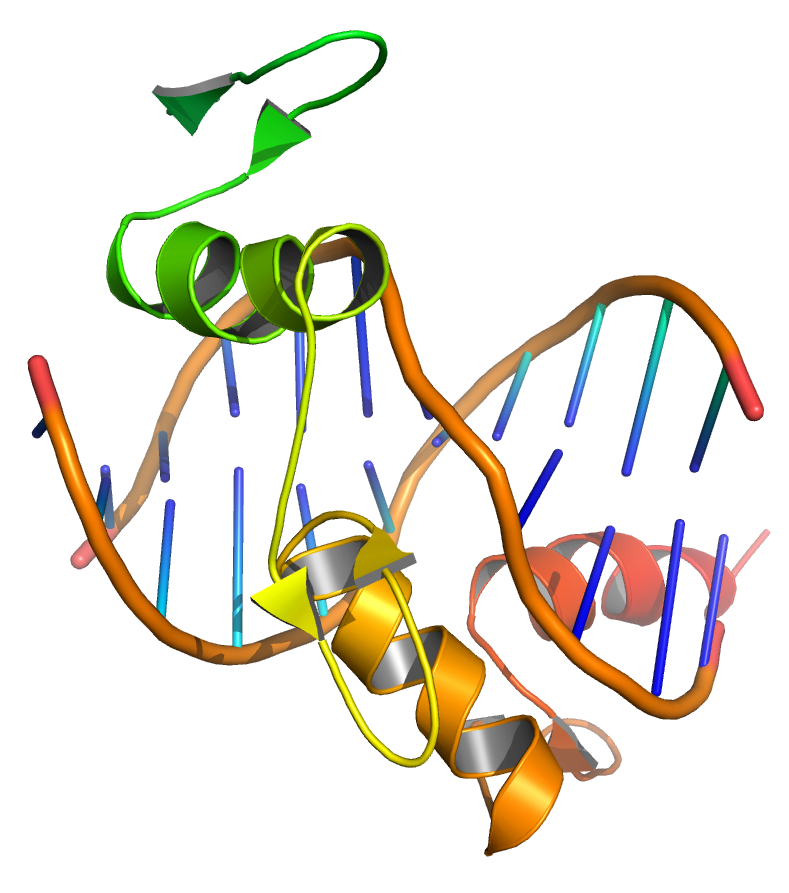

The genome of a given organism contains thousands of genes, but not all these genes need to be active at any given moment. A gene is expressed when it is being transcribed into mRNA and there exist many cellular methods of controlling the expression of genes such that proteins are produced only when needed by the cell. Transcription factors are regulatory proteins that bind to DNA, either promoting or inhibiting the transcription of a gene. Within the genome of Escherichia coli bacteria, for example, there exists a series of genes necessary for the synthesis of the amino acid tryptophan. However, when tryptophan is already available to the cell, these genes for tryptophan synthesis are no longer needed. The presence of tryptophan directly affects the activity of the genes—tryptophan molecules bind to the tryptophan repressor (a transcription factor), changing the repressor’s structure such that the repressor binds to the genes. The tryptophan repressor blocks the transcription and expression of the genes, thereby creating negative feedback regulation of the tryptophan synthesis process.

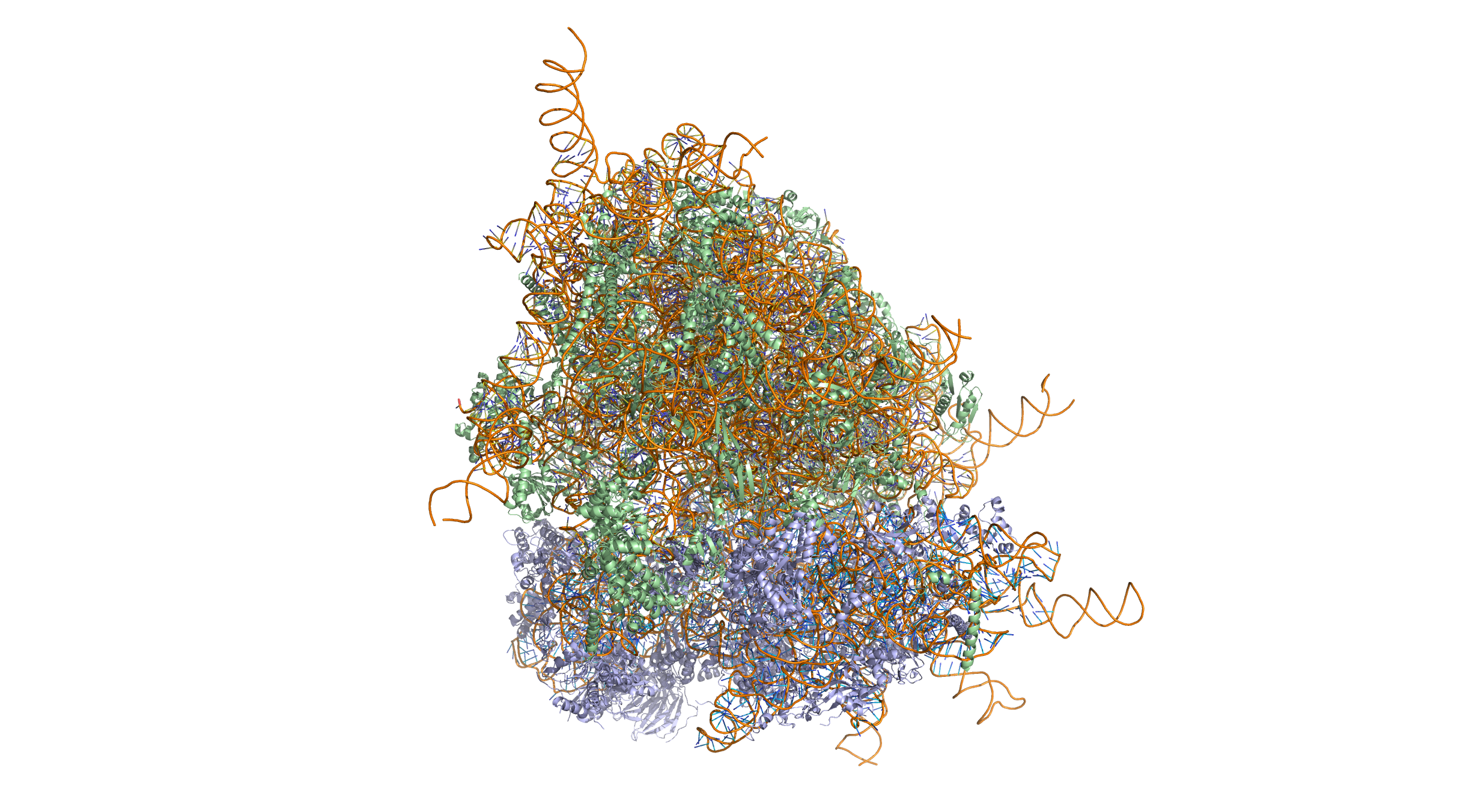

Figure 9.3: Transcription factors bind to DNA, influencing the transcription of associated genes. Based on atomic coordinates of PDB 1A1L, rendered with open source molecular visualization tool PyMol.

Differences in gene expression are especially clear within multicellular organisms, where cells all contain the same genome but have very different structures and behaviors due to the expression of different sets of genes. All the cells in a multicellular organism derive from a single cell, differentiating into variant cell types in response to external and intercellular signals and gradually establishing different patterns of gene expression to create different behaviors. As no single gene is responsible for the development of structures within multicellular organisms, these patterns arise from the complex interactions between many cells.

Within eukaryotes, there exist structural features of chromatin that influence the transcription of genes, often in the form of modifications to DNA and chromatin that are stably inherited by daughter cells. These features are called “epigenetic” because they exist “on top” of the DNA sequence and retain inheritance from one cell generation to the next. Because of epigenetic features, different cell types grown within the same medium can retain very different properties. Although epigenetic features are generally dynamic over the course of development, some, like the phenomenon of paramutation, have multigenerational inheritance and exist as rare exceptions to the general rule of DNA as the basis for inheritance.

9.2.4 Genetic Change

During the process of DNA replication, errors occasionally occur in the polymerization of the second strand. These errors, called mutations, can affect the phenotype of an organism, especially if they occur within the protein coding sequence of a gene. Error rates are usually very low—1 error in every 10–100 million bases—due to the “proofreading” ability of DNA polymerases. Processes that increase the rate of changes in DNA are called mutagenic: mutagenic chemicals promote errors in DNA replication, often by interfering with the structure of base-pairing, while UV radiation induces mutations by causing damage to the DNA structure. Chemical damage to DNA occurs naturally as well and cells use DNA repair mechanisms to repair mismatches and breaks. The repair does not, however, always restore the original sequence.

In organisms that use chromosomal crossover to exchange DNA and recombine genes, errors in alignment during meiosis can also cause mutations. Errors in crossover are especially likely when similar sequences cause partner chromosomes to adopt a mistaken alignment; this makes some regions in genomes more prone to mutating in this way. These errors create large structural changes in DNA sequence – duplications, inversions, deletions of entire regions – or the accidental exchange of whole parts of sequences between different chromosomes (chromosomal translocation).

9.2.5 Natural Selection And Evolution

Mutations alter an organism’s genotype and occasionally this causes different phenotypes to appear. Most mutations have little effect on an organism’s phenotype, health, or reproductive fitness. Mutations that do have an effect are usually detrimental, but occasionally some can be beneficial. Studies in the fly Drosophila melanogaster suggest that if a mutation changes a protein produced by a gene, about 70 percent of these mutations will be harmful with the remainder being either neutral or weakly beneficial.

Population genetics studies the distribution of genetic differences within populations and how these distributions change over time. Changes in the frequency of an allele in a population are mainly influenced by natural selection, where a given allele provides a selective or reproductive advantage to the organism, as well as other factors such as mutation, genetic drift, genetic hitchhiking, artificial selection and migration.

Over many generations, the genomes of organisms can change significantly, resulting in evolution. In the process called adaptation, selection for beneficial mutations can cause a species to evolve into forms better able to survive in their environment. New species are formed through the process of speciation, often caused by geographical separations that prevent populations from exchanging genes with each other.

By comparing the homology between different species’ genomes, it is possible to calculate the evolutionary distance between them and when they may have diverged. Genetic comparisons are generally considered a more accurate method of characterizing the relatedness between species than the comparison of phenotypic characteristics. The evolutionary distances between species can be used to form evolutionary trees; these trees represent the common descent and divergence of species over time, although they do not show the transfer of genetic material between unrelated species (known as horizontal gene transfer and most common in bacteria).

9.3 Bacterial Genetics

Bacterial genetics is the subfield of genetics devoted to the study of bacteria. Bacterial genetics are subtly different from eukaryotic genetics, however bacteria still serve as a good model for animal genetic studies. One of the major distinctions between bacterial and eukaryotic genetics stems from the bacteria’s lack of membrane-bound organelles (this is true of all prokaryotes. While it is a fact that there are prokaryotic organelles, they are never bound by a lipid membrane, but by a shell of proteins), necessitating protein synthesis occur in the cytoplasm.

Since the discovery of microorganisms by Robert Hooke and Antoni van Leeuwenhoek during the period 1665-1885 they have been used to study many processes and have had applications in various areas of study in genetics. For example: Microorganisms’ rapid growth rates and short generation times are used by scientists to study evolution. Robert Hooke and Antoni van Leeuwenhoek discoveries involved depictions, observations, and descriptions of microorganisms. Mucor is the microfungus that Hooke presented and gave a depiction of. His contribution being, Mucor as the first microorganism to be illustrated. Antoni van Leeuwenhoek’s contribution to the microscopic protozoa and microscopic bacteria yielded to scientific observations and descriptions. These contributions were accomplished by a simple microscope, which led to the understanding of microbes today and continues to progress scientists understanding. Microbial genetics also has applications in being able to study processes and pathways that are similar to those found in humans such as drug metabolism. Genetically modified bacteria were the first organisms to be modified in the laboratory, due to their simple genetics. These organisms are now used for several purposes, and are particularly important in producing large amounts of pure human proteins for use in medicine.

Most bacteria have a single circular chromosome that can range in size from only 160,000 base pairs in the endosymbiotic bacteria Carsonella ruddii, to 12,200,000 base pairs (12.2 Mbp) in the soil-dwelling bacteria Sorangium cellulosum. There are many exceptions to this, for example some Streptomyces and Borrelia species contain a single linear chromosome, while some Vibrio species contain more than one chromosome. Bacteria can also contain plasmids, small extra-chromosomal molecules of DNA that may contain genes for various useful functions such as antibiotic resistance, metabolic capabilities, or various virulence factors.

Bacteria genomes usually encode a few hundred to a few thousand genes. The genes in bacterial genomes are usually a single continuous stretch of DNA and although several different types of introns do exist in bacteria, these are much rarer than in eukaryotes.

Bacteria, as asexual organisms, inherit an identical copy of the parent’s genomes and are clonal. However, all bacteria can evolve by selection on changes to their genetic material DNA caused by genetic recombination or mutations. Mutations come from errors made during the replication of DNA or from exposure to mutagens. Mutation rates vary widely among different species of bacteria and even among different clones of a single species of bacteria. Genetic changes in bacterial genomes come from either random mutation during replication or “stress-directed mutation”, where genes involved in a particular growth-limiting process have an increased mutation rate.

Some bacteria also transfer genetic material between cells. This can occur in three main ways. First, bacteria can take up exogenous DNA from their environment, in a process called transformation. Many bacteria can naturally take up DNA from the environment, while others must be chemically altered in order to induce them to take up DNA. The development of competence in nature is usually associated with stressful environmental conditions, and seems to be an adaptation for facilitating repair of DNA damage in recipient cells. The second way bacteria transfer genetic material is by transduction, when the integration of a bacteriophage introduces foreign DNA into the chromosome. Many types of bacteriophage exist, some simply infect and lyse their host bacteria, while others insert into the bacterial chromosome. Bacteria resist phage infection through restriction modification systems that degrade foreign DNA, and a system that uses CRISPR sequences to retain fragments of the genomes of phage that the bacteria have come into contact with in the past, which allows them to block virus replication through a form of RNA interference. The third method of gene transfer is conjugation, whereby DNA is transferred through direct cell contact. In ordinary circumstances, transduction, conjugation, and transformation involve transfer of DNA between individual bacteria of the same species, but occasionally transfer may occur between individuals of different bacterial species and this may have significant consequences, such as the transfer of antibiotic resistance. In such cases, gene acquisition from other bacteria or the environment is called horizontal gene transfer and may be common under natural conditions.

Like other organisms, bacteria also breed true and maintain their characteristics from generation to generation, yet at the same time, exhibit variations in particular properties in a small proportion of their progeny. Though heritability and variations in bacteria had been noticed from the early days of bacteriology, it was not realised then that bacteria too obey the laws of genetics. Even the existence of a bacterial nucleus was a subject of controversy. The differences in morphology and other properties were attributed by Nageli in 1877, to bacterial pleomorphism, which postulated the existence of a single, a few species of bacteria, which possessed a protein capacity for a variation. With the development and application of precise methods of pure culture, it became apparent that different types of bacteria retained constant form and function through successive generations. This led to the concept of monomorphism.

9.3.1 Bacterial Plasmids

A plasmid is a small, extrachromosomal DNA molecule within a cell that is physically separated from chromosomal DNA and can replicate independently. They are most commonly found as small circular, double-stranded DNA molecules in bacteria; however, plasmids are sometimes present in archaea and eukaryotic organisms. In nature, plasmids often carry genes that benefit the survival of the organism and confer selective advantage such as antibiotic resistance. While chromosomes are large and contain all the essential genetic information for living under normal conditions, plasmids are usually very small and contain only additional genes that may be useful in certain situations or conditions. Artificial plasmids are widely used as vectors in molecular cloning, serving to drive the replication of recombinant DNA sequences within host organisms. In the laboratory, plasmids may be introduced into a cell via transformation. Synthetic plasmids are available for procurement over the internet.

Figure 9.4: A line drawing of a bacterium with its chromosomal DNA and several plasmids. he bacterium is drawn as a large oval. Within the bacterium, small to medium size circles illustrate the plasmids, and one long thin closed line that intersects itself repeatedly illustrates the chromosomal DNA.

Plasmids are considered replicons, units of DNA capable of replicating autonomously within a suitable host. However, plasmids, like viruses, are not generally classified as life. Plasmids are transmitted from one bacterium to another (even of another species) mostly through conjugation. This host-to-host transfer of genetic material is one mechanism of horizontal gene transfer, and plasmids are considered part of the mobilome. Unlike viruses, which encase their genetic material in a protective protein coat called a capsid, plasmids are “naked” DNA and do not encode genes necessary to encase the genetic material for transfer to a new host; however, some classes of plasmids encode the conjugative “sex” pilus necessary for their own transfer. The size of the plasmid varies from 1 to over 200 kbp, and the number of identical plasmids in a single cell can range anywhere from one to thousands under some circumstances.

The term plasmid was introduced in 1952 by the American molecular biologist Joshua Lederberg to refer to “any extrachromosomal hereditary determinant.” The term’s early usage included any bacterial genetic material that exists extrachromosomally for at least part of its replication cycle, but because that description includes bacterial viruses, the notion of plasmid was refined over time to comprise genetic elements that reproduce autonomously. Later in 1968, it was decided that the term plasmid should be adopted as the term for extrachromosomal genetic element, and to distinguish it from viruses, the definition was narrowed to genetic elements that exist exclusively or predominantly outside of the chromosome and can replicate autonomously.

In order for plasmids to replicate independently within a cell, they must possess a stretch of DNA that can act as an origin of replication. The self-replicating unit, in this case, the plasmid, is called a replicon. A typical bacterial replicon may consist of a number of elements, such as the gene for plasmid-specific replication initiation protein (Rep), repeating units called iterons, DnaA boxes, and an adjacent AT-rich region. Smaller plasmids make use of the host replicative enzymes to make copies of themselves, while larger plasmids may carry genes specific for the replication of those plasmids. A few types of plasmids can also insert into the host chromosome, and these integrative plasmids are sometimes referred to as episomes in prokaryotes.

Plasmids almost always carry at least one gene. Many of the genes carried by a plasmid are beneficial for the host cells, for example: enabling the host cell to survive in an environment that would otherwise be lethal or restrictive for growth. Some of these genes encode traits for antibiotic resistance or resistance to heavy metal, while others may produce virulence factors that enable a bacterium to colonize a host and overcome its defences or have specific metabolic functions that allow the bacterium to utilize a particular nutrient, including the ability to degrade recalcitrant or toxic organic compounds. Plasmids can also provide bacteria with the ability to fix nitrogen. Some plasmids, however, have no observable effect on the phenotype of the host cell or its benefit to the host cells cannot be determined, and these plasmids are called cryptic plasmids.

Naturally occurring plasmids vary greatly in their physical properties. Their size can range from very small mini-plasmids of less than 1-kilobase pairs (Kbp) to very large megaplasmids of several megabase pairs (Mbp). At the upper end, little differs between a megaplasmid and a minichromosome. Plasmids are generally circular, but examples of linear plasmids are also known. These linear plasmids require specialized mechanisms to replicate their ends.

Plasmids may be present in an individual cell in varying number, ranging from one to several hundreds. The normal number of copies of plasmid that may be found in a single cell is called the plasmid copy number, and is determined by how the replication initiation is regulated and the size of the molecule. Larger plasmids tend to have lower copy numbers. Low-copy-number plasmids that exist only as one or a few copies in each bacterium are, upon cell division, in danger of being lost in one of the segregating bacteria. Such single-copy plasmids have systems that attempt to actively distribute a copy to both daughter cells. These systems, which include the parABS system and parMRC system, are often referred to as the partition system or partition function of a plasmid.

9.3.2 Bacterial Transformation

In molecular biology and genetics, transformation is the genetic alteration of a cell resulting from the direct uptake and incorporation of exogenous genetic material from its surroundings through the cell membrane(s). For transformation to take place, the recipient bacterium must be in a state of competence, which might occur in nature as a time-limited response to environmental conditions such as starvation and cell density, and may also be induced in a laboratory.

Figure 9.5: In this diagram , a gene from bacterial cell 1 is moved from bacterial cell 1 to bacterial cell 2. This process of bacterial cell 2 taking up new genetic material is called transformation. Step I: The DNA of a bacterial cell is located in the cytoplasm (1), but also in the plasmid, an independent, circular loop of DNA. The gene to be transferred (4) is located on the plasmid of cell 1 (3), but not on the plasmid of bacterial cell 2 (2). In order to remove the gene from the plasmid of bacterial cell 1, a restriction enzyme (5) is used. The restriction enzyme binds to a specific site on the DNA and “cuts” it, releasing the satisfactory gene. Genes are naturally removed and released into the environment usually after a cell dies and disintegrates. Step II: Bacterial cell 2 takes up the gene. This integration of genetic material from the environment is an evolutionary tool and is common in bacterial cells. Step III: The enzyme DNA ligase (6) adds the gene to the plasmid of bacterial cell 2 by forming chemical bonds between the two segments which join them together. Step IV: The plasmid of bacterial cell 2 now contains the gene from bacterial cell 1 (7). The gene has been transferred from one bacterial cell to another, and transformation is complete.

Transformation is one of three processes for horizontal gene transfer, in which exogenous genetic material passes from one bacterium to another, the other two being conjugation (transfer of genetic material between two bacterial cells in direct contact) and transduction (injection of foreign DNA by a bacteriophage virus into the host bacterium). In transformation, the genetic material passes through the intervening medium, and uptake is completely dependent on the recipient bacterium.

As of 2014 about 80 species of bacteria were known to be capable of transformation, about evenly divided between Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria; the number might be an overestimate since several of the reports are supported by single papers.

“Transformation” may also be used to describe the insertion of new genetic material into nonbacterial cells, including animal and plant cells; however, because “transformation” has a special meaning in relation to animal cells, indicating progression to a cancerous state, the process is usually called “transfection”.

Transformation in bacteria was first demonstrated in 1928 by the British bacteriologist Frederick Griffith. Griffith was interested in determining whether injections of heat-killed bacteria could be used to vaccinate mice against pneumonia. However, he discovered that a non-virulent strain of Streptococcus pneumoniae could be made virulent after being exposed to heat-killed virulent strains. Griffith hypothesized that some “transforming principle” from the heat-killed strain was responsible for making the harmless strain virulent. In 1944 this “transforming principle” was identified as being genetic by Oswald Avery, Colin MacLeod, and Maclyn McCarty. They isolated DNA from a virulent strain of S. pneumoniae and using just this DNA were able to make a harmless strain virulent. They called this uptake and incorporation of DNA by bacteria “transformation” (See Avery-MacLeod-McCarty experiment) The results of Avery et al.’s experiments were at first skeptically received by the scientific community and it was not until the development of genetic markers and the discovery of other methods of genetic transfer (conjugation in 1947 and transduction in 1953) by Joshua Lederberg that Avery’s experiments were accepted.

It was originally thought that Escherichia coli, a commonly used laboratory organism, was refractory to transformation. However, in 1970, Morton Mandel and Akiko Higa showed that E. coli may be induced to take up DNA from bacteriophage λ without the use of helper phage after treatment with calcium chloride solution. Two years later in 1972, Stanley Norman Cohen, Annie Chang and Leslie Hsu showed that CaCl 2 treatment is also effective for transformation of plasmid DNA. The method of transformation by Mandel and Higa was later improved upon by Douglas Hanahan. The discovery of artificially induced competence in E. coli created an efficient and convenient procedure for transforming bacteria which allows for simpler molecular cloning methods in biotechnology and research, and it is now a routinely used laboratory procedure.

Transformation using electroporation was developed in the late 1980s, increasing the efficiency of in-vitro transformation and increasing the number of bacterial strains that could be transformed. Transformation of animal and plant cells was also investigated with the first transgenic mouse being created by injecting a gene for a rat growth hormone into a mouse embryo in 1982. In 1897 a bacterium that caused plant tumors, Agrobacterium tumefaciens, was discovered and in the early 1970s the tumor-inducing agent was found to be a DNA plasmid called the Ti plasmid. By removing the genes in the plasmid that caused the tumor and adding in novel genes, researchers were able to infect plants with A. tumefaciens and let the bacteria insert their chosen DNA into the genomes of the plants. Not all plant cells are susceptible to infection by A. tumefaciens, so other methods were developed, including electroporation and micro-injection. Particle bombardment was made possible with the invention of the Biolistic Particle Delivery System (gene gun) by John Sanford in the 1980s.

Naturally competent bacteria carry sets of genes that provide the protein machinery to bring DNA across the cell membrane(s). The transport of the exogenous DNA into the cells may require proteins that are involved in the assembly of type IV pili and type II secretion system, as well as DNA translocase complex at the cytoplasmic membrane.

Due to the differences in structure of the cell envelope between Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, there are some differences in the mechanisms of DNA uptake in these cells, however most of them share common features that involve related proteins. The DNA first binds to the surface of the competent cells on a DNA receptor, and passes through the cytoplasmic membrane via DNA translocase. Only single-stranded DNA may pass through, the other strand being degraded by nucleases in the process. The translocated single-stranded DNA may then be integrated into the bacterial chromosomes by a RecA-dependent process. In Gram-negative cells, due to the presence of an extra membrane, the DNA requires the presence of a channel formed by secretins on the outer membrane. Pilin may be required for competence, but its role is uncertain. The uptake of DNA is generally non-sequence specific, although in some species the presence of specific DNA uptake sequences may facilitate efficient DNA uptake.

Natural transformation is a bacterial adaptation for DNA transfer that depends on the expression of numerous bacterial genes whose products appear to be responsible for this process. In general, transformation is a complex, energy-requiring developmental process. In order for a bacterium to bind, take up and recombine exogenous DNA into its chromosome, it must become competent, that is, enter a special physiological state. Competence development in Bacillus subtilis requires expression of about 40 genes. The DNA integrated into the host chromosome is usually (but with rare exceptions) derived from another bacterium of the same species, and is thus homologous to the resident chromosome.

In B. subtilis the length of the transferred DNA is greater than 1271 kb (more than 1 million bases). The length transferred is likely double stranded DNA and is often more than a third of the total chromosome length of 4215 kb. It appears that about 7-9% of the recipient cells take up an entire chromosome.

The capacity for natural transformation appears to occur in a number of prokaryotes, and thus far 67 prokaryotic species (in seven different phyla) are known to undergo this process.

Competence for transformation is typically induced by high cell density and/or nutritional limitation, conditions associated with the stationary phase of bacterial growth. Transformation in Haemophilus influenzae occurs most efficiently at the end of exponential growth as bacterial growth approaches stationary phase. Transformation in Streptococcus mutans, as well as in many other streptococci, occurs at high cell density and is associated with biofilm formation. Competence in B. subtilis is induced toward the end of logarithmic growth, especially under conditions of amino acid limitation. Similarly, in Micrococcus luteus (a representative of the less well studied Actinobacteria phylum), competence develops during the mid-late exponential growth phase and is also triggered by amino acids starvation.

By releasing intact host and plasmid DNA, certain bacteriophages are thought to contribute to transformation.

Competence is specifically induced by DNA damaging conditions. For instance, transformation is induced in Streptococcus pneumoniae by the DNA damaging agents mitomycin C (a DNA cross-linking agent) and fluoroquinolone (a topoisomerase inhibitor that causes double-strand breaks). In B. subtilis, transformation is increased by UV light, a DNA damaging agent. In Helicobacter pylori, ciprofloxacin, which interacts with DNA gyrase and introduces double-strand breaks, induces expression of competence genes, thus enhancing the frequency of transformation Using Legionella pneumophila, Charpentier et al. tested 64 toxic molecules to determine which of these induce competence. Of these, only six, all DNA damaging agents, caused strong induction. These DNA damaging agents were mitomycin C (which causes DNA inter-strand crosslinks), norfloxacin, ofloxacin and nalidixic acid (inhibitors of DNA gyrase that cause double-strand breaks), bicyclomycin (causes single- and double-strand breaks), and hydroxyurea (induces DNA base oxidation). UV light also induced competence in L. pneumophila. Charpentier et al. suggested that competence for transformation probably evolved as a DNA damage response.

Logarithmically growing bacteria differ from stationary phase bacteria with respect to the number of genome copies present in the cell, and this has implications for the capability to carry out an important DNA repair process. During logarithmic growth, two or more copies of any particular region of the chromosome may be present in a bacterial cell, as cell division is not precisely matched with chromosome replication. The process of homologous recombinational repair (HRR) is a key DNA repair process that is especially effective for repairing double-strand damages, such as double-strand breaks. This process depends on a second homologous chromosome in addition to the damaged chromosome. During logarithmic growth, a DNA damage in one chromosome may be repaired by HRR using sequence information from the other homologous chromosome. Once cells approach stationary phase, however, they typically have just one copy of the chromosome, and HRR requires input of homologous template from outside the cell by transformation.

To test whether the adaptive function of transformation is repair of DNA damages, a series of experiments were carried out using B. subtilis irradiated by UV light as the damaging agent (reviewed by Michod et al. and Bernstein et al.) The results of these experiments indicated that transforming DNA acts to repair potentially lethal DNA damages introduced by UV light in the recipient DNA. The particular process responsible for repair was likely HRR. Transformation in bacteria can be viewed as a primitive sexual process, since it involves interaction of homologous DNA from two individuals to form recombinant DNA that is passed on to succeeding generations. Bacterial transformation in prokaryotes may have been the ancestral process that gave rise to meiotic sexual reproduction in eukaryotes (see Evolution of sexual reproduction; Meiosis.)

Artificial competence can be induced in laboratory procedures that involve making the cell passively permeable to DNA by exposing it to conditions that do not normally occur in nature. Typically the cells are incubated in a solution containing divalent cations (often calcium chloride) under cold conditions, before being exposed to a heat pulse (heat shock). Calcium chloride partially disrupts the cell membrane, which allows the recombinant DNA to enter the host cell. Cells that are able to take up the DNA are called competent cells.

It has been found that growth of Gram-negative bacteria in 20 mM Mg reduces the number of protein-to-lipopolysaccharide bonds by increasing the ratio of ionic to covalent bonds, which increases membrane fluidity, facilitating transformation. The role of lipopolysaccharides here are verified from the observation that shorter O-side chains are more effectively transformed – perhaps because of improved DNA accessibility.

The surface of bacteria such as E. coli is negatively charged due to phospholipids and lipopolysaccharides on its cell surface, and the DNA is also negatively charged. One function of the divalent cation therefore would be to shield the charges by coordinating the phosphate groups and other negative charges, thereby allowing a DNA molecule to adhere to the cell surface.

DNA entry into E. coli cells is through channels known as zones of adhesion or Bayer’s junction, with a typical cell carrying as many as 400 such zones. Their role was established when cobalamine (which also uses these channels) was found to competitively inhibit DNA uptake. Another type of channel implicated in DNA uptake consists of poly (HB):poly P:Ca. In this poly (HB) is envisioned to wrap around DNA (itself a polyphosphate), and is carried in a shield formed by Ca ions.

It is suggested that exposing the cells to divalent cations in cold condition may also change or weaken the cell surface structure, making it more permeable to DNA. The heat-pulse is thought to create a thermal imbalance across the cell membrane, which forces the DNA to enter the cells through either cell pores or the damaged cell wall.

Electroporation is another method of promoting competence. In this method the cells are briefly shocked with an electric field of 10-20 kV/cm, which is thought to create holes in the cell membrane through which the plasmid DNA may enter. After the electric shock, the holes are rapidly closed by the cell’s membrane-repair mechanisms.

9.3.3 Practical aspects of transformation in molecular biology

The discovery of artificially induced competence in bacteria allow bacteria such as Escherichia coli to be used as a convenient host for the manipulation of DNA as well as expressing proteins. Typically plasmids are used for transformation in E. coli. In order to be stably maintained in the cell, a plasmid DNA molecule must contain an origin of replication, which allows it to be replicated in the cell independently of the replication of the cell’s own chromosome.

The efficiency with which a competent culture can take up exogenous DNA and express its genes is known as transformation efficiency and is measured in colony forming unit (cfu) per μg DNA used. A transformation efficiency of 1×108 cfu/μg for a small plasmid like pUC19 is roughly equivalent to 1 in 2000 molecules of the plasmid used being transformed.

In calcium chloride transformation, the cells are prepared by chilling cells in the presence of Ca2+ (in CaCl2 solution), making the cell become permeable to plasmid DNA. The cells are incubated on ice with the DNA, and then briefly heat-shocked (e.g., at 42 °C for 30–120 seconds). This method works very well for circular plasmid DNA. Non-commercial preparations should normally give 106 to 107 transformants per microgram of plasmid; a poor preparation will be about 104/μg or less, but a good preparation of competent cells can give up to ~108 colonies per microgram of plasmid. Protocols, however, exist for making supercompetent cells that may yield a transformation efficiency of over 109. The chemical method, however, usually does not work well for linear DNA, such as fragments of chromosomal DNA, probably because the cell’s native exonuclease enzymes rapidly degrade linear DNA. In contrast, cells that are naturally competent are usually transformed more efficiently with linear DNA than with plasmid DNA.

The transformation efficiency using the CaCl2 method decreases with plasmid size, and electroporation therefore may be a more effective method for the uptake of large plasmid DNA. Cells used in electroporation should be prepared first by washing in cold double-distilled water to remove charged particles that may create sparks during the electroporation process.

9.3.4 Selection and screening in plasmid transformation

Because transformation usually produces a mixture of relatively few transformed cells and an abundance of non-transformed cells, a method is necessary to select for the cells that have acquired the plasmid. The plasmid therefore requires a selectable marker such that those cells without the plasmid may be killed or have their growth arrested. Antibiotic resistance is the most commonly used marker for prokaryotes. The transforming plasmid contains a gene that confers resistance to an antibiotic that the bacteria are otherwise sensitive to. The mixture of treated cells is cultured on media that contain the antibiotic so that only transformed cells are able to grow. Another method of selection is the use of certain auxotrophic markers that can compensate for an inability to metabolise certain amino acids, nucleotides, or sugars. This method requires the use of suitably mutated strains that are deficient in the synthesis or utility of a particular biomolecule, and the transformed cells are cultured in a medium that allows only cells containing the plasmid to grow.

In a cloning experiment, a gene may be inserted into a plasmid used for transformation. However, in such experiment, not all the plasmids may contain a successfully inserted gene. Additional techniques may therefore be employed further to screen for transformed cells that contain plasmid with the insert. Reporter genes can be used as markers, such as the lacZ gene which codes for β-galactosidase used in blue-white screening. This method of screening relies on the principle of α-complementation, where a fragment of the lacZ gene (lacZα) in the plasmid can complement another mutant lacZ gene (lacZΔM15) in the cell. Both genes by themselves produce non-functional peptides, however, when expressed together, as when a plasmid containing lacZ-α is transformed into a lacZΔM15 cells, they form a functional β-galactosidase. The presence of an active β-galactosidase may be detected when cells are grown in plates containing X-gal, forming characteristic blue colonies. However, the multiple cloning site, where a gene of interest may be ligated into the plasmid vector, is located within the lacZα gene. Successful ligation therefore disrupts the lacZα gene, and no functional β-galactosidase can form, resulting in white colonies. Cells containing successfully ligated insert can then be easily identified by its white coloration from the unsuccessful blue ones.

Other commonly used reporter genes are green fluorescent protein (GFP), which produces cells that glow green under blue light, and the enzyme luciferase, which catalyzes a reaction with luciferin to emit light. The recombinant DNA may also be detected using other methods such as nucleic acid hybridization with radioactive RNA probe, while cells that expressed the desired protein from the plasmid may also be detected using immunological methods.

9.3.5 Bacterial Conjugation

Bacterial conjugation is the transfer of genetic material between bacterial cells by direct cell-to-cell contact or by a bridge-like connection between two cells. This takes place through a pilus. It is a parasexual mode of reproduction in bacteria. The process was discovered by Joshua Lederberg and Edward Tatum in 1946.

It is a mechanism of horizontal gene transfer as are transformation and transduction although these two other mechanisms do not involve cell-to-cell contact.

Classical E. coli bacterial conjugation is often regarded as the bacterial equivalent of sexual reproduction or mating since it involves the exchange of genetic material. However, it is not sexual reproduction, since no exchange of gamete occurs, and indeed no generation of a new organism: instead an existing organism is transformed. During classical E. coli conjugation the donor cell provides a conjugative or mobilizable genetic element that is most often a plasmid or transposon. Most conjugative plasmids have systems ensuring that the recipient cell does not already contain a similar element.

The genetic information transferred is often beneficial to the recipient. Benefits may include antibiotic resistance, xenobiotic tolerance or the ability to use new metabolites. Other elements can be detrimental and may be viewed as bacterial parasites.

Conjugation in Escherichia coli by spontaneous zygogenesis and in Mycobacterium smegmatis by distributive conjugal transfer differ from the better studied classical E. coli conjugation in that these cases involve substantial blending of the parental genomes.

Figure 9.6: Schematic drawing of bacterial conjugation. Conjugation diagram 1) Donor cell produces pilus. 2) Pilus attaches to recipient cell, brings the two cells together. 3) The mobile plasmid is nicked and a single strand of DNA is then transferred to the recipient cell. 4) Both cells recircularize their plasmids, synthesize second strands, and reproduce pili; both cells are now viable donors.

The F-plasmid is an episome (a plasmid that can integrate itself into the bacterial chromosome by homologous recombination) with a length of about 100 kb. It carries its own origin of replication, the oriV, and an origin of transfer, or oriT. There can only be one copy of the F-plasmid in a given bacterium, either free or integrated, and bacteria that possess a copy are called F-positive or F-plus (denoted F+). Cells that lack F plasmids are called F-negative or F-minus (F−) and as such can function as recipient cells.

Among other genetic information, the F-plasmid carries a tra and trb locus, which together are about 33 kb long and consist of about 40 genes. The tra locus includes the pilin gene and regulatory genes, which together form pili on the cell surface. The locus also includes the genes for the proteins that attach themselves to the surface of F− bacteria and initiate conjugation. Though there is some debate on the exact mechanism of conjugation it seems that the pili are not the structures through which DNA exchange occurs. This has been shown in experiments where the pilus are allowed to make contact, but then are denatured with SDS and yet DNA transformation still proceeds. Several proteins coded for in the tra or trb locus seem to open a channel between the bacteria and it is thought that the traD enzyme, located at the base of the pilus, initiates membrane fusion.

When conjugation is initiated by a signal the relaxase enzyme creates a nick in one of the strands of the conjugative plasmid at the oriT. Relaxase may work alone or in a complex of over a dozen proteins known collectively as a relaxosome. In the F-plasmid system the relaxase enzyme is called TraI and the relaxosome consists of TraI, TraY, TraM and the integrated host factor IHF. The nicked strand, or T-strand, is then unwound from the unbroken strand and transferred to the recipient cell in a 5’-terminus to 3’-terminus direction. The remaining strand is replicated either independent of conjugative action (vegetative replication beginning at the oriV) or in concert with conjugation (conjugative replication similar to the rolling circle replication of lambda phage). Conjugative replication may require a second nick before successful transfer can occur. A recent report claims to have inhibited conjugation with chemicals that mimic an intermediate step of this second nicking event.

If the F-plasmid that is transferred has previously been integrated into the donor’s genome (producing an Hfr strain [“High Frequency of Recombination”]) some of the donor’s chromosomal DNA may also be transferred with the plasmid DNA. The amount of chromosomal DNA that is transferred depends on how long the two conjugating bacteria remain in contact. In common laboratory strains of E. coli the transfer of the entire bacterial chromosome takes about 100 minutes. The transferred DNA can then be integrated into the recipient genome via homologous recombination.

A cell culture that contains in its population cells with non-integrated F-plasmids usually also contains a few cells that have accidentally integrated their plasmids. It is these cells that are responsible for the low-frequency chromosomal gene transfers that occur in such cultures. Some strains of bacteria with an integrated F-plasmid can be isolated and grown in pure culture. Because such strains transfer chromosomal genes very efficiently they are called Hfr (high frequency of recombination). The E. coli genome was originally mapped by interrupted mating experiments in which various Hfr cells in the process of conjugation were sheared from recipients after less than 100 minutes (initially using a Waring blender). The genes that were transferred were then investigated.

Since integration of the F-plasmid into the E. coli chromosome is a rare spontaneous occurrence, and since the numerous genes promoting DNA transfer are in the plasmid genome rather than in the bacterial genome, it has been argued that conjugative bacterial gene transfer, as it occurs in the E. coli Hfr system, is not an evolutionary adaptation of the bacterial host, nor is it likely ancestral to eukaryotic sex.

9.4 Structure And Function Of Deoxyribonucleic Acid

Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) is a molecule composed of two chains that coil around each other to form a double helix carrying genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth and reproduction of all known organisms and many viruses. DNA and ribonucleic acid (RNA) are nucleic acids; alongside proteins, lipids and complex carbohydrates (polysaccharides), nucleic acids are one of the four major types of macromolecules that are essential for all known forms of life.

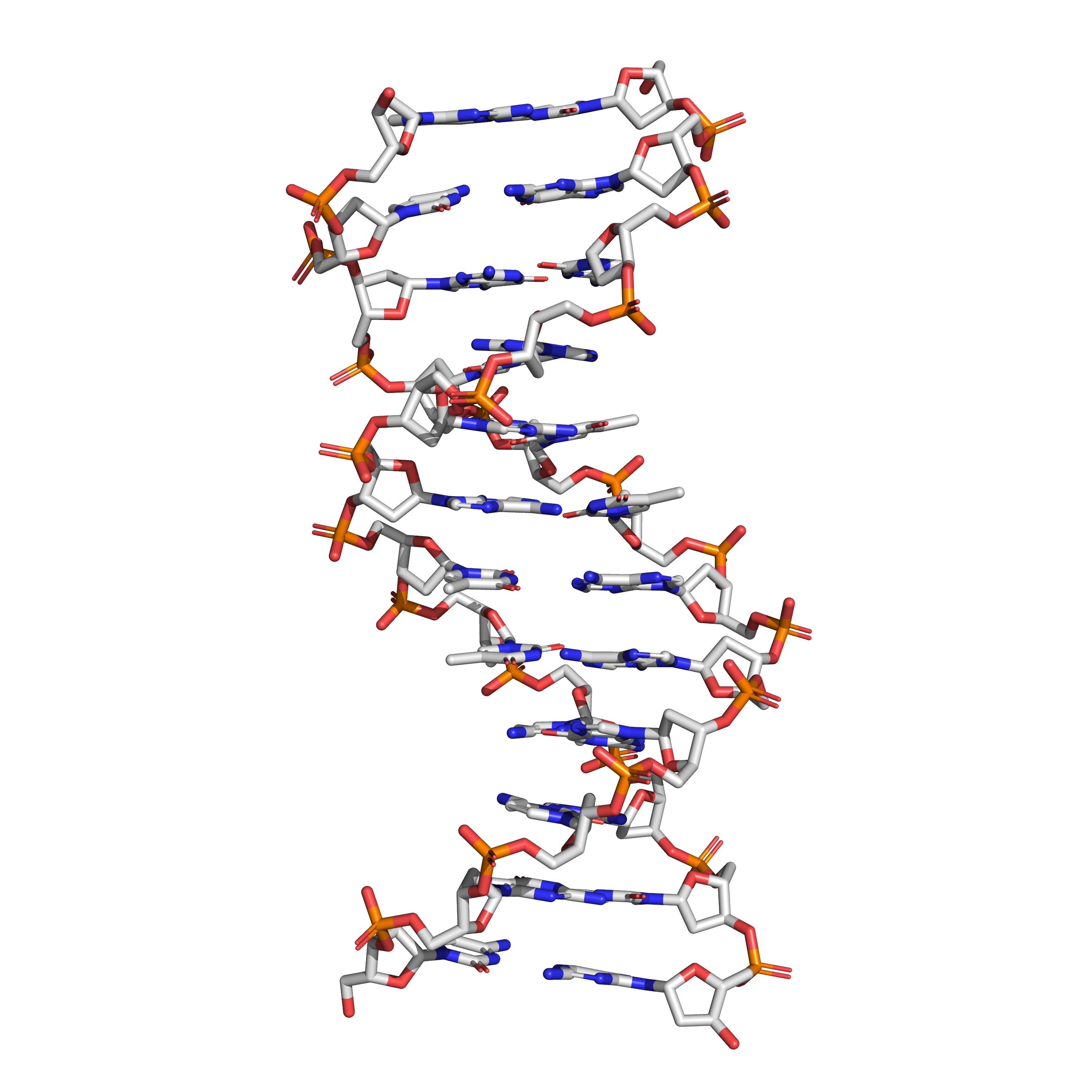

Figure 9.7: The structure of the DNA double helix. A section of DNA. The bases lie horizontally between the two spiraling strands. The atoms in the structure are colour-coded by element (based on atomic coordinates of PDB 1bna rendered with open source molecular visualization tool PyMol.)

The two DNA strands are also known as polynucleotides as they are composed of simpler monomeric units called nucleotides. Each nucleotide is composed of one of four nitrogen-containing nucleobases (cytosine [C], guanine [G], adenine [A] or thymine [T]), a sugar called deoxyribose, and a phosphate group. The nucleotides are joined to one another in a chain by covalent bonds between the sugar of one nucleotide and the phosphate of the next, resulting in an alternating sugar-phosphate backbone. The nitrogenous bases of the two separate polynucleotide strands are bound together, according to base pairing rules (A with T and C with G), with hydrogen bonds to make double-stranded DNA. The complementary nitrogenous bases are divided into two groups, pyrimidines and purines. In DNA, the pyrimidines are thymine and cytosine; the purines are adenine and guanine.

Figure 9.8: The structure of the four nucleotides and their base pairing in the DNA double helix. The atoms in the structure are colour-coded by element (based on atomic coordinates of PDB 1bna rendered with open source molecular visualization tool PyMol.)

Both strands of DNA store biological information. This information is replicated as and when the two strands separate. A large part of DNA (more than 98% for humans) is non-coding, meaning that these sections do not serve as patterns for protein sequences. The two strands of DNA run in opposite directions to each other and are thus antiparallel. Attached to each sugar is one of four types of nucleobases (informally, bases). It is the sequence of these four nucleobases along the backbone that encodes genetic information. RNA strands are created using DNA strands as a template in a process called transcription, where DNA bases are exchanged for their corresponding bases except in the case of thymine (T), which RNA substitutes for uracil (U). Under the genetic code, these RNA strands specify the sequence of amino acids within proteins in a process called translation.

Within eukaryotic cells, DNA is organized into long structures called chromosomes. Before typical cell division, these chromosomes are duplicated in the process of DNA replication, providing a complete set of chromosomes for each daughter cell. Eukaryotic organisms (animals, plants, fungi and protists) store most of their DNA inside the cell nucleus as nuclear DNA, and some in the mitochondria as mitochondrial DNA or in chloroplasts as chloroplast DNA. In contrast, prokaryotes (bacteria and archaea) store their DNA only in the cytoplasm, in circular chromosomes. Within eukaryotic chromosomes, chromatin proteins, such as histones, compact and organize DNA. These compacting structures guide the interactions between DNA and other proteins, helping control which parts of the DNA are transcribed.

DNA was first isolated by Friedrich Miescher in 1869. Its molecular structure was first identified by Francis Crick and James Watson at the Cavendish Laboratory within the University of Cambridge in 1953, whose model-building efforts were guided by X-ray diffraction data acquired by Raymond Gosling, who was a post-graduate student of Rosalind Franklin.

DNA is a long polymer made from repeating units called nucleotides, each of which is usually symbolized by a single letter: either A, T, C, or G. The structure of DNA is dynamic along its length, being capable of coiling into tight loops and other shapes. In all species it is composed of two helical chains, bound to each other by hydrogen bonds. Both chains are coiled around the same axis, and have the same pitch of 34 angstroms (Å) (3.4 nanometres). The pair of chains has a radius of 10 angstroms (1.0 nanometre). Although each individual nucleotide is very small, a DNA polymer can be very large and contain hundreds of millions, such as in chromosome 1. Chromosome 1 is the largest human chromosome with approximately 220 million base pairs, and would be 85 mm long if straightened.

DNA does not usually exist as a single strand, but instead as a pair of strands that are held tightly together. These two long strands coil around each other, in the shape of a double helix. The nucleotide contains both a segment of the backbone of the molecule (which holds the chain together) and a nucleobase (which interacts with the other DNA strand in the helix). A nucleobase linked to a sugar is called a nucleoside, and a base linked to a sugar and to one or more phosphate groups is called a nucleotide. A biopolymer comprising multiple linked nucleotides (as in DNA) is called a polynucleotide.

The backbone of the DNA strand is made from alternating phosphate and sugar residues. The sugar in DNA is 2-deoxyribose, which is a pentose (five-carbon) sugar. The sugars are joined together by phosphate groups that form phosphodiester bonds between the third and fifth carbon atoms of adjacent sugar rings. These are known as the 3′-end (three prime end), and 5′-end (five prime end) carbons, the prime symbol being used to distinguish these carbon atoms from those of the base to which the deoxyribose forms a glycosidic bond. When imagining DNA, each phosphoryl is normally considered to “belong” to the nucleotide whose 5′ carbon forms a bond therewith. Any DNA strand therefore normally has one end at which there is a phosphoryl attached to the 5′ carbon of a ribose (the 5′ phosphoryl) and another end at which there is a free hydroxyl attached to the 3′ carbon of a ribose (the 3′ hydroxyl). The orientation of the 3′ and 5′ carbons along the sugar-phosphate backbone confers directionality (sometimes called polarity) to each DNA strand. In a nucleic acid double helix, the direction of the nucleotides in one strand is opposite to their direction in the other strand: the strands are antiparallel. The asymmetric ends of DNA strands are said to have a directionality of five prime end (5′ ), and three prime end (3′), with the 5′ end having a terminal phosphate group and the 3′ end a terminal hydroxyl group. One major difference between DNA and RNA is the sugar, with the 2-deoxyribose in DNA being replaced by the alternative pentose sugar ribose in RNA.

Twin helical strands form the DNA backbone. Another double helix may be found tracing the spaces, or grooves, between the strands (Figure 9.9). These voids are adjacent to the base pairs and may provide a binding site. As the strands are not symmetrically located with respect to each other, the grooves are unequally sized. One groove, the major groove, is 22 angstroms (Å) wide and the other, the minor groove, is 12 Å wide. The width of the major groove means that the edges of the bases are more accessible in the major groove than in the minor groove. As a result, proteins such as transcription factors that can bind to specific sequences in double-stranded DNA usually make contact with the sides of the bases exposed in the major groove.

Figure 9.9: DNA major and minor grooves. PDB 1bna rendered with open source molecular visualization tool PyMol.)

In a DNA double helix, each type of nucleobase on one strand bonds with just one type of nucleobase on the other strand. This is called complementary base pairing. Here, purines form hydrogen bonds to pyrimidines, with adenine bonding only to thymine in two hydrogen bonds, and cytosine bonding only to guanine in three hydrogen bonds (Figure 9.10). This arrangement of two nucleotides binding together across the double helix is called a Watson-Crick base pair. As hydrogen bonds are not covalent, they can be broken and rejoined relatively easily. The two strands of DNA in a double helix can thus be pulled apart like a zipper, either by a mechanical force or high temperature. As a result of this base pair complementarity, all the information in the double-stranded sequence of a DNA helix is duplicated on each strand, which is vital in DNA replication. This reversible and specific interaction between complementary base pairs is critical for all the functions of DNA in organisms.

Figure 9.10: Top, a GC base pair with three hydrogen bonds. Bottom, an AT base pair with two hydrogen bonds. Non-covalent hydrogen bonds between the pairs are shown as dashed lines. The two types of base pairs form different numbers of hydrogen bonds, AT forming two hydrogen bonds, and GC forming three hydrogen bonds (see figures, right). DNA with high GC-content is more stable than DNA with low GC-content.

As noted above, most DNA molecules are actually two polymer strands, bound together in a helical fashion by noncovalent bonds; this double-stranded (dsDNA) structure is maintained largely by the intrastrand base stacking interactions, which are strongest for G,C stacks. The two strands can come apart—a process known as melting—to form two single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) molecules. Melting occurs at high temperature, low salt and high pH (low pH also melts DNA, but since DNA is unstable due to acid depurination, low pH is rarely used).

The stability of the dsDNA form depends not only on the GC-content (% G,C basepairs) but also on sequence (since stacking is sequence specific) and also length (longer molecules are more stable). The stability can be measured in various ways; a common way is the “melting temperature”, which is the temperature at which 50% of the ds molecules are converted to ss molecules; melting temperature is dependent on ionic strength and the concentration of DNA. As a result, it is both the percentage of GC base pairs and the overall length of a DNA double helix that determines the strength of the association between the two strands of DNA. Long DNA helices with a high GC-content have stronger-interacting strands, while short helices with high AT content have weaker-interacting strands. In biology, parts of the DNA double helix that need to separate easily, such as the TATAAT Pribnow box in some promoters, tend to have a high AT content, making the strands easier to pull apart.

In the laboratory, the strength of this interaction can be measured by finding the temperature necessary to break the hydrogen bonds, their melting temperature (also called Tm value). When all the base pairs in a DNA double helix melt, the strands separate and exist in solution as two entirely independent molecules. These single-stranded DNA molecules have no single common shape, but some conformations are more stable than others.

A DNA sequence is called a “sense” sequence if it is the same as that of a messenger RNA copy that is translated into protein. The sequence on the opposite strand is called the “antisense” sequence. Both sense and antisense sequences can exist on different parts of the same strand of DNA (i.e. both strands can contain both sense and antisense sequences). In both prokaryotes and eukaryotes, antisense RNA sequences are produced, but the functions of these RNAs are not entirely clear. One proposal is that antisense RNAs are involved in regulating gene expression through RNA-RNA base pairing.

A few DNA sequences in prokaryotes and eukaryotes, and more in plasmids and viruses, blur the distinction between sense and antisense strands by having overlapping genes. In these cases, some DNA sequences do double duty, encoding one protein when read along one strand, and a second protein when read in the opposite direction along the other strand. In bacteria, this overlap may be involved in the regulation of gene transcription, while in viruses, overlapping genes increase the amount of information that can be encoded within the small viral genome.

DNA can be twisted like a rope in a process called DNA supercoiling. With DNA in its “relaxed” state, a strand usually circles the axis of the double helix once every 10.4 base pairs, but if the DNA is twisted the strands become more tightly or more loosely wound. If the DNA is twisted in the direction of the helix, this is positive supercoiling, and the bases are held more tightly together. If they are twisted in the opposite direction, this is negative supercoiling, and the bases come apart more easily. In nature, most DNA has slight negative supercoiling that is introduced by enzymes called topoisomerases. These enzymes are also needed to relieve the twisting stresses introduced into DNA strands during processes such as transcription and DNA replication.

The expression of genes is influenced by how the DNA is packaged in chromosomes, in a structure called chromatin. Base modifications can be involved in packaging, with regions that have low or no gene expression usually containing high levels of methylation of cytosine bases. DNA packaging and its influence on gene expression can also occur by covalent modifications of the histone protein core around which DNA is wrapped in the chromatin structure or else by remodeling carried out by chromatin remodeling complexes. There is, further, crosstalk between DNA methylation and histone modification, so they can coordinately affect chromatin and gene expression.

For one example, cytosine methylation produces 5-methylcytosine, which is important for X-inactivation of chromosomes. The average level of methylation varies between organisms—the worm Caenorhabditis elegans lacks cytosine methylation, while vertebrates have higher levels, with up to 1% of their DNA containing 5-methylcytosine. Despite the importance of 5-methylcytosine, it can deaminate to leave a thymine base, so methylated cytosines are particularly prone to mutations. Other base modifications include adenine methylation in bacteria, the presence of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in the brain, and the glycosylation of uracil to produce the “J-base” in kinetoplastids.

9.4.1 DNA Damage

DNA can be damaged by many sorts of mutagens, which change the DNA sequence. Mutagens include oxidizing agents, alkylating agents and also high-energy electromagnetic radiation such as ultraviolet light and X-rays. The type of DNA damage produced depends on the type of mutagen. For example, UV light can damage DNA by producing thymine dimers, which are cross-links between pyrimidine bases. On the other hand, oxidants such as free radicals or hydrogen peroxide produce multiple forms of damage, including base modifications, particularly of guanosine, and double-strand breaks. A typical human cell contains about 150,000 bases that have suffered oxidative damage. Of these oxidative lesions, the most dangerous are double-strand breaks, as these are difficult to repair and can produce point mutations, insertions, deletions from the DNA sequence, and chromosomal translocations. These mutations can cause cancer. DNA damage that is naturally occurring, due to normal cellular processes that produce reactive oxygen species, the hydrolytic activities of cellular water, etc., also occurs frequently. Although most of this damage is repaired, in any cell some DNA damage may remain despite the action of repair processes. This DNA damage accumulates with age in mammalian postmitotic tissues. This accumulation appears to be an important underlying cause of aging.