3 Methods Of Studying Microorganisms

3.1 Microscopy

Microscopy is the technical field of using microscopes to view objects and areas of objects that cannot be seen with the naked eye (objects that are not within the resolution range of the normal eye). There are three well-known branches of microscopy: optical, electron, and scanning probe microscopy, along with the emerging field of X-ray microscopy.

Optical microscopy and electron microscopy involve the diffraction, reflection, or refraction of electromagnetic radiation/electron beams interacting with the specimen, and the collection of the scattered radiation or another signal in order to create an image. This process may be carried out by wide-field irradiation of the sample (for example standard light microscopy and transmission electron microscopy) or by scanning a fine beam over the sample (for example confocal laser scanning microscopy and scanning electron microscopy). Scanning probe microscopy involves the interaction of a scanning probe with the surface of the object of interest. The development of microscopy revolutionized biology, gave rise to the field of histology and so remains an essential technique in the life and physical sciences. X-ray microscopy is three-dimensional and non-destructive, allowing for repeated imaging of the same sample for in situ or 4D studies, and providing the ability to “see inside” the sample being studied before sacrificing it to higher resolution techniques. A 3D X-ray microscope uses the technique of computed tomography (microCT), rotating the sample 360 degrees and reconstructing the images. CT is typically carried out with a flat panel display. A 3D X-ray microscope employs a range of objectives, e.g., from 4X to 40X, and can also include a flat panel.

The field of microscopy (optical microscopy) dates back to at least the 17th-century. Earlier microscopes, single lens magnifying glasses with limited magnification, date at least as far back as the wide spread use of lenses in eyeglasses in the 13th century but more advanced compound microscopes first appeared in Europe around 1620 The earliest practitioners of microscopy include Galileo Galilei, who found in 1610 that he could close focus his telescope to view small objects close up and Cornelis Drebbel, who may have invented the compound microscope around 1620 Antonie van Leeuwenhoek developed a very high magnification simple microscope in the 1670s and is often considered to be the first acknowledged microscopist and microbiologist.

3.1.1 Light Microscopy

Optical or light microscopy involves passing visible light transmitted through or reflected from the sample through a single lens or multiple lenses to allow a magnified view of the sample. The resulting image can be detected directly by the eye, imaged on a photographic plate, or captured digitally. The single lens with its attachments, or the system of lenses and imaging equipment, along with the appropriate lighting equipment, sample stage, and support, makes up the basic light microscope. The most recent development is the digital microscope, which uses a CCD camera to focus on the exhibit of interest. The image is shown on a computer screen, so eye-pieces are unnecessary.

3.1.2 The Optical (Light) Microscope

The optical microscope, also referred to as a light microscope, is a type of microscope that commonly uses visible light and a system of lenses to generate magnified images of small objects. Optical microscopes are the oldest design of microscope and were possibly invented in their present compound form in the 17th century. Basic optical microscopes can be very simple, although many complex designs aim to improve resolution and sample contrast.

The object is placed on a stage and may be directly viewed through one or two eyepieces on the microscope. In high-power microscopes, both eyepieces typically show the same image, but with a stereo microscope, slightly different images are used to create a 3-D effect. A camera is typically used to capture the image (micrograph).

The sample can be lit in a variety of ways. Transparent objects can be lit from below and solid objects can be lit with light coming through (bright field) or around (dark field) the objective lens. Polarised light may be used to determine crystal orientation of metallic objects. Phase-contrast imaging can be used to increase image contrast by highlighting small details of differing refractive index.

A range of objective lenses with different magnification are usually provided mounted on a turret, allowing them to be rotated into place and providing an ability to zoom-in. The maximum magnification power of optical microscopes is typically limited to around 1000x because of the limited resolving power of visible light. The magnification of a compound optical microscope is the product of the magnification of the eyepiece (say 10x) and the objective lens (say 100x), to give a total magnification of 1,000×. Modified environments such as the use of oil or ultraviolet light can increase the magnification.

Alternatives to optical microscopy which do not use visible light include scanning electron microscopy and transmission electron microscopy and scanning probe microscopy and as a result, can achieve much greater magnifications.

There are two basic types of optical microscopes: simple microscopes and compound microscopes. A simple microscope uses the optical power of single lens or group of lenses for magnification. A compound microscope uses a system of lenses (one set enlarging the image produced by another) to achieve much higher magnification of an object. The vast majority of modern research microscopes are compound microscopes while some cheaper commercial digital microscopes are simple single lens microscopes. Compound microscopes can be further divided into a variety of other types of microscopes which differ in their optical configurations, cost, and intended purposes.

3.1.3 Simple Microscope

A simple microscope uses a lens or set of lenses to enlarge an object through angular magnification alone, giving the viewer an erect enlarged virtual image. The use of a single convex lens or groups of lenses are found in simple magnification devices such as the magnifying glass, loupes, and eyepieces for telescopes and microscopes.

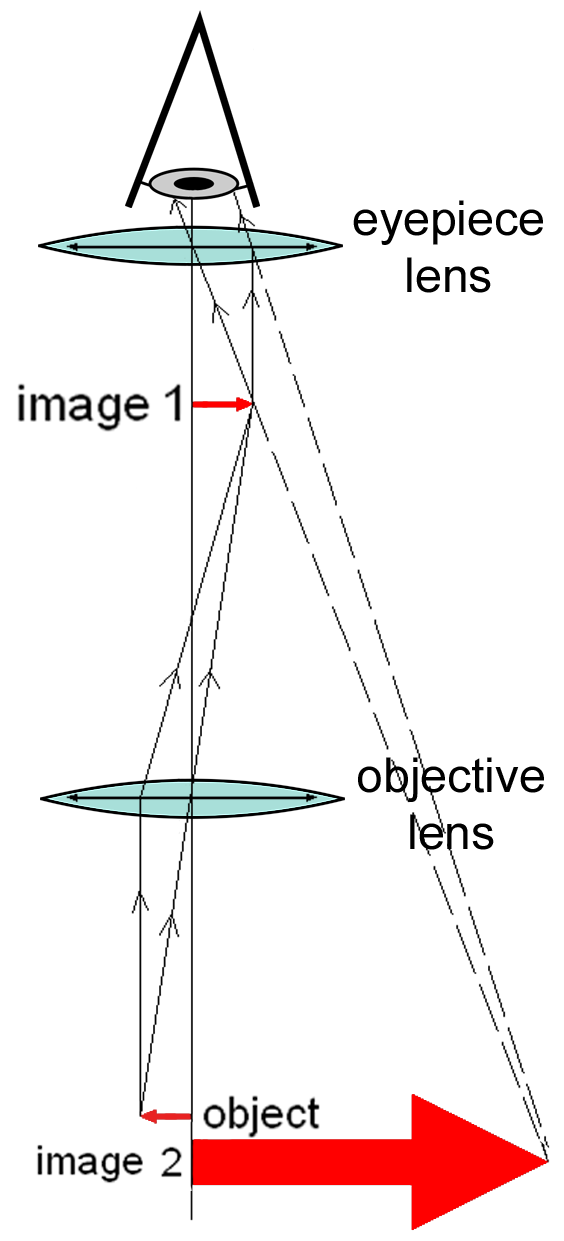

3.1.4 Compound Microscope

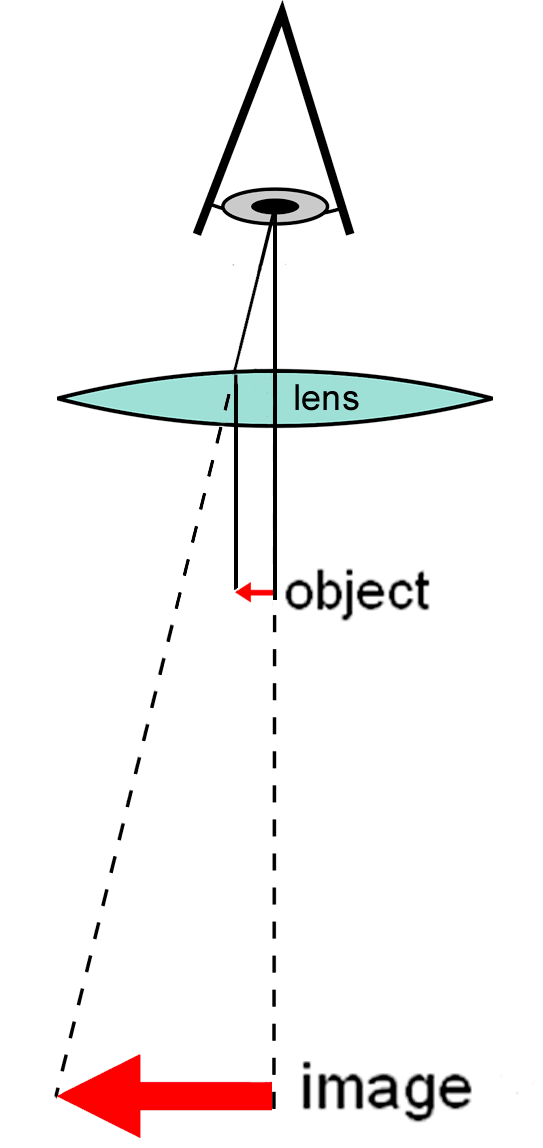

A compound microscope uses a lens close to the object being viewed to collect light (called the objective lens) which focuses a real image of the object inside the microscope (image 1). That image is then magnified by a second lens or group of lenses (called the eyepiece) that gives the viewer an enlarged inverted virtual image of the object (image 2). The use of a compound objective/eyepiece combination allows for much higher magnification. Common compound microscopes often feature exchangeable objective lenses, allowing the user to quickly adjust the magnification. A compound microscope also enables more advanced illumination setups, such as phase contrast.

Figure 3.4: Diagram of a compound microscope.

3.1.5 The Main Components Of The Light Microscope

All modern optical microscopes designed for viewing samples by transmitted light share the same basic components of the light path. In addition, the vast majority of microscopes have the same ‘structural’ components (numbered below according to the image on the right):

- Eyepiece (ocular lens) (1)

- Objective turret, revolver, or revolving nose piece (to hold multiple objective lenses) (2)

- Objective lenses (3)

- Focus knobs (to move the stage)

- Coarse adjustment (4)

- Fine adjustment (5)

- Stage (to hold the specimen) (6)

- Light source (a light or a mirror) (7)

- Diaphragm and condenser (8)

- Mechanical stage (9)

3.1.6 Eyepiece (Ocular Lens)

The eyepiece, or ocular lens, is a cylinder containing two or more lenses; its function is to bring the image into focus for the eye. The eyepiece is inserted into the top end of the body tube. Eyepieces are interchangeable and many different eyepieces can be inserted with different degrees of magnification. Typical magnification values for eyepieces include 5×, 10× (the most common), 15× and 20×. In some high performance microscopes, the optical configuration of the objective lens and eyepiece are matched to give the best possible optical performance. This occurs most commonly with apochromatic objectives.

Objective turret (revolver or revolving nose piece) Objective turret, revolver, or revolving nose piece is the part that holds the set of objective lenses. It allows the user to switch between objective lenses.

3.1.7 Objective Lens

At the lower end of a typical compound optical microscope, there are one or more objective lenses that collect light from the sample. The objective is usually in a cylinder housing containing a glass single or multi-element compound lens. Typically there will be around three objective lenses screwed into a circular nose piece which may be rotated to select the required objective lens. These arrangements are designed to be parfocal, which means that when one changes from one lens to another on a microscope, the sample stays in focus. Microscope objectives are characterized by two parameters, namely, magnification and numerical aperture. The former typically ranges from 5× to 100× while the latter ranges from 0.14 to 0.7, corresponding to focal lengths of about 40 to 2 mm, respectively. Objective lenses with higher magnifications normally have a higher numerical aperture and a shorter depth of field in the resulting image. Some high performance objective lenses may require matched eyepieces to deliver the best optical performance.

3.1.8 Oil Immersion Objective

Some microscopes make use of oil-immersion objectives or water-immersion objectives for greater resolution at high magnification. These are used with index-matching material such as immersion oil or water and a matched cover slip between the objective lens and the sample. The refractive index of the index-matching material is higher than air allowing the objective lens to have a larger numerical aperture (greater than 1) so that the light is transmitted from the specimen to the outer face of the objective lens with minimal refraction. Numerical apertures as high as 1.6 can be achieved. The larger numerical aperture allows collection of more light making detailed observation of smaller details possible. An oil immersion lens usually has a magnification of 40 to 100×.

3.1.9 Focus Knobs

Adjustment knobs move the stage up and down with separate adjustment for coarse and fine focusing. The same controls enable the microscope to adjust to specimens of different thickness. In older designs of microscopes, the focus adjustment wheels move the microscope tube up or down relative to the stand and had a fixed stage.

3.1.10 The Frame

The whole of the optical assembly is traditionally attached to a rigid arm, which in turn is attached to a robust U-shaped foot to provide the necessary rigidity. The arm angle may be adjustable to allow the viewing angle to be adjusted.

The frame provides a mounting point for various microscope controls. Normally this will include controls for focusing, typically a large knurled wheel to adjust coarse focus, together with a smaller knurled wheel to control fine focus. Other features may be lamp controls and/or controls for adjusting the condenser.

3.1.11 The Stage

The stage is a platform below the objective lens which supports the specimen being viewed. In the center of the stage is a hole through which light passes to illuminate the specimen. The stage usually has arms to hold slides (rectangular glass plates with typical dimensions of 25×75 mm, on which the specimen is mounted).

At magnifications higher than 100× moving a slide by hand is not practical. A mechanical stage, typical of medium and higher priced microscopes, allows tiny movements of the slide via control knobs that reposition the sample/slide as desired. If a microscope did not originally have a mechanical stage it may be possible to add one.

All stages move up and down for focus. With a mechanical stage slides move on two horizontal axes for positioning the specimen to examine specimen details.

Focusing starts at lower magnification in order to center the specimen by the user on the stage. Moving to a higher magnification requires the stage to be moved higher vertically for re-focus at the higher magnification and may also require slight horizontal specimen position adjustment. Horizontal specimen position adjustments are the reason for having a mechanical stage.

Due to the difficulty in preparing specimens and mounting them on slides, for children it’s best to begin with prepared slides that are centered and focus easily regardless of the focus level used.

3.1.12 The Light Source

Many sources of light can be used. At its simplest, daylight is directed via a mirror. Most microscopes, however, have their own adjustable and controllable light source – often a halogen lamp, although illumination using LEDs and lasers are becoming a more common provision. Köhler illumination is often provided on more expensive instruments.

3.1.13 The Condenser

The condenser is a lens designed to focus light from the illumination source onto the sample. The condenser may also include other features, such as a diaphragm and/or filters, to manage the quality and intensity of the illumination. For illumination techniques like dark field, phase contrast and differential interference contrast microscopy additional optical components must be precisely aligned in the light path.

3.1.14 Magnification

The actual power or magnification of a compound optical microscope is the product of the powers of the ocular (eyepiece) and the objective lens. The maximum normal magnifications of the ocular and objective are 10× and 100× respectively, giving a final magnification of 1,000×.

When using a camera to capture a micrograph the effective magnification of the image must take into account the size of the image. This is independent of whether it is on a print from a film negative or displayed digitally on a computer screen.

In the case of photographic film cameras the calculation is simple; the final magnification is the product of: the objective lens magnification, the camera optics magnification and the enlargement factor of the film print relative to the negative. A typical value of the enlargement factor is around 5× (for the case of 35 mm film and a 15 × 10 cm (6 × 4 inch) print).

In the case of digital cameras the size of the pixels in the CMOS or CCD detector and the size of the pixels on the screen have to be known. The enlargement factor from the detector to the pixels on screen can then be calculated. As with a film camera the final magnification is the product of: the objective lens magnification, the camera optics magnification and the enlargement factor

At very high magnifications with transmitted light, point objects are seen as fuzzy discs surrounded by diffraction rings. These are called Airy disks. The resolving power of a microscope is taken as the ability to distinguish between two closely spaced Airy disks (or, in other words the ability of the microscope to reveal adjacent structural detail as distinct and separate). It is these impacts of diffraction that limit the ability to resolve fine details. The extent and magnitude of the diffraction patterns are affected by both the wavelength of light (λ), the refractive materials used to manufacture the objective lens and the numerical aperture (NA) of the objective lens. There is therefore a finite limit beyond which it is impossible to resolve separate points in the objective field, known as the diffraction limit. Assuming that optical aberrations in the whole optical set-up are negligible, the resolution d, can be stated as:

\[ d={\frac {\lambda }{2NA}}\]

Usually a wavelength of 550 nm is assumed, which corresponds to green light. With air as the external medium, the highest practical NA is 0.95, and with oil, up to 1.5. In practice the lowest value of d obtainable with conventional lenses is about 200 nm. A new type of lens using multiple scattering of light allowed to improve the resolution to below 100 nm.

3.1.15 The Microscope Slide

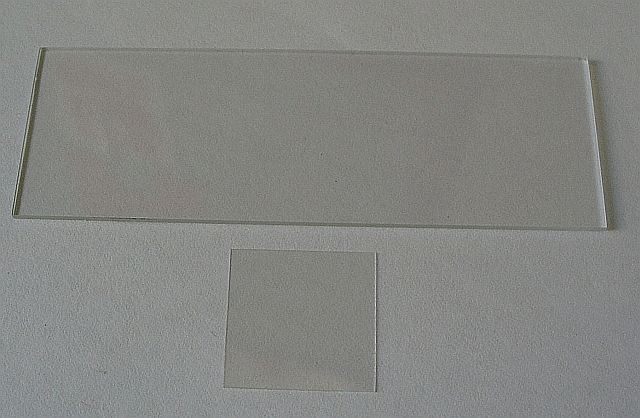

A microscope slide is a thin flat piece of glass, typically 75 by 26 mm (3 by 1 inches) and about 1 mm thick, used to hold objects for examination under a microscope. Typically the object is mounted (secured) on the slide, and then both are inserted together in the microscope for viewing. This arrangement allows several slide-mounted objects to be quickly inserted and removed from the microscope, labeled, transported, and stored in appropriate slide cases or folders etc.

Microscope slides are often used together with a cover slip or cover glass, a smaller and thinner sheet of glass that is placed over the specimen. Slides are held in place on the microscope’s stage by slide clips, slide clamps or a cross-table which is used to achieve precise, remote movement of the slide upon the microscope’s stage (such as in an automated/computer operated system, or where touching the slide with fingers is inappropriate either due to the risk of contamination or lack of precision).

The mounting of specimens on microscope slides is often critical for successful viewing. The problem has been given much attention in the last two centuries and is a well-developed area with many specialized and sometimes quite sophisticated techniques. Specimens are often held into place using the smaller glass cover slips.

The main function of the cover slip is to keep solid specimens pressed flat, and liquid samples shaped into a flat layer of even thickness. This is necessary because high-resolution microscopes have a very narrow region within which they focus.

The cover glass often has several other functions. It holds the specimen in place (either by the weight of the cover slip or, in the case of a wet mount, by surface tension) and protects the specimen from dust and accidental contact. It protects the microscope’s objective lens from contacting the specimen and vice versa; in oil immersion microscopy or water immersion microscopy the cover slip prevents contact between the immersion liquid and the specimen. The cover slip can be glued to the slide so as to seal off the specimen, retarding dehydration and oxidation of the specimen and also preventing contamination. A number of sealants are in use, including commercial sealants, laboratory preparations, or even regular clear nail polish, depending on the sample. A solvent-free sealant that can be used for live cell samples is “valap”, a mixture of vaseline, lanolin and paraffin in equal parts. Microbial and cell cultures can be grown directly on the cover slip before it is placed on the slide, and specimens may be permanently mounted on the slip instead of on the slide.

Cover slips are available in a range of sizes and thicknesses. Using the wrong thickness can result in spherical aberration and a reduction in resolution and image intensity. Specialty objectives may used to image specimens without coverslips, or may have correction collars that permit a user to accommodate for alternative coverslip thickness.

3.1.16 Dry Mount

In a dry mount, the simplest kind of mounting, the object is merely placed on the slide. A cover slip may be placed on top to protect the specimen and the microscope’s objective and to keep the specimen still and pressed flat. This mounting can be successfully used for viewing specimens like pollen, feathers, hairs, etc. It is also used to examine particles caught in transparent membrane filters (e.g., in analysis of airborne dust).

3.1.17 Wet Mount Or Temporary Mount

In a wet mount, the specimen is placed in a drop of water or other liquid held between the slide and the cover slip by surface tension. This method is commonly used, for example, to view microscopic organisms that grow in pond water or other liquid media, especially when studying their movement and behavior. Care must be taken to exclude air bubbles that would interfere with the viewing and hamper the organisms’ movements. An example of a temporary wet mount is a lactofuchsin mount, which provides both a sample mounting, as well as a fuchsine staining.

3.1.18 Prepared Mount Or Permanent Mount

For pathological and biological research, the specimen usually undergoes a complex histological preparation that involves fixing it to prevent decay, removing any water contained in it, replacing the water with paraffin, cutting it into very thin sections using a microtome, placing the sections on a microscope slide, staining the tissue using various stains to reveal specific tissue components, clearing the tissue to render it transparent and covering it with a coverslip and mounting medium.

3.1.19 Techniques Of Optical Microscopy

Optical or light microscopy involves passing visible light transmitted through or reflected from the sample through a single lens or multiple lenses to allow a magnified view of the sample.[11] The resulting image can be detected directly by the eye, imaged on a photographic plate, or captured digitally. The single lens with its attachments, or the system of lenses and imaging equipment, along with the appropriate lighting equipment, sample stage, and support, makes up the basic light microscope. The most recent development is the digital microscope, which uses a CCD camera to focus on the exhibit of interest. The image is shown on a computer screen, so eye-pieces are unnecessary.

Limitations of standard optical microscopy (bright field microscopy) lie in three areas;

- This technique can only image dark or strongly refracting objects effectively.

- There is a diffraction-limited resolution depending on incident wavelength; in visible range, the resolution of optical microscopy is limited to approximately 0.2 micrometres (see: microscope) and the practical magnification limit to ~1500x.

- Out-of-focus light from points outside the focal plane reduces image clarity.

Live cells in particular generally lack sufficient contrast to be studied successfully, since the internal structures of the cell are colorless and transparent. The most common way to increase contrast is to stain the different structures with selective dyes, but this often involves killing and fixing the sample. Staining may also introduce artifacts, which are apparent structural details that are caused by the processing of the specimen and are thus not legitimate features of the specimen. In general, these techniques make use of differences in the refractive index of cell structures. Bright-field microscopy is comparable to looking through a glass window: one sees not the glass but merely the dirt on the glass. There is a difference, as glass is a denser material, and this creates a difference in phase of the light passing through. The human eye is not sensitive to this difference in phase, but clever optical solutions have been devised to change this difference in phase into a difference in amplitude (light intensity).

In order to improve specimen contrast or highlight certain structures in a sample, special techniques must be used. A huge selection of microscopy techniques are available to increase contrast or label a sample.

3.1.20 Bright Field

Bright field microscopy is the simplest of all the light microscopy techniques. Sample illumination is via transmitted white light, i.e. illuminated from below and observed from above. Limitations include low contrast of most biological samples and low apparent resolution due to the blur of out-of-focus material. The simplicity of the technique and the minimal sample preparation required are significant advantages.

3.1.21 Oblique Illumination

The use of oblique (from the side) illumination gives the image a three-dimensional (3D) appearance and can highlight otherwise invisible features. A more recent technique based on this method is Hoffmann’s modulation contrast, a system found on inverted microscopes for use in cell culture. Oblique illumination suffers from the same limitations as bright field microscopy (low contrast of many biological samples; low apparent resolution due to out of focus objects).

3.1.22 Dark Field

Dark field microscopy is a technique for improving the contrast of unstained, transparent specimens. Dark field illumination uses a carefully aligned light source to minimize the quantity of directly transmitted (unscattered) light entering the image plane, collecting only the light scattered by the sample. Dark field can dramatically improve image contrast – especially of transparent objects – while requiring little equipment setup or sample preparation. However, the technique suffers from low light intensity in final image of many biological samples and continues to be affected by low apparent resolution.

Rheinberg illumination is a special variant of dark field illumination in which transparent, colored filters are inserted just before the condenser so that light rays at high aperture are differently colored than those at low aperture (i.e., the background to the specimen may be blue while the object appears self-luminous red). Other color combinations are possible, but their effectiveness is quite variable.

3.1.23 Dispersion Staining

Dispersion staining is an optical technique that results in a colored image of a colorless object. This is an optical staining technique and requires no stains or dyes to produce a color effect. There are five different microscope configurations used in the broader technique of dispersion staining. They include brightfield Becke line, oblique, darkfield, phase contrast, and objective stop dispersion staining.

3.1.24 Phase Contrast

More sophisticated techniques will show proportional differences in optical density. Phase contrast is a widely used technique that shows differences in refractive index as difference in contrast. It was developed by the Dutch physicist Frits Zernike in the 1930s (for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1953). The nucleus in a cell for example will show up darkly against the surrounding cytoplasm. Contrast is excellent; however it is not for use with thick objects. Frequently, a halo is formed even around small objects, which obscures detail. The system consists of a circular annulus in the condenser, which produces a cone of light. This cone is superimposed on a similar sized ring within the phase-objective. Every objective has a different size ring, so for every objective another condenser setting has to be chosen. The ring in the objective has special optical properties: it, first of all, reduces the direct light in intensity, but more importantly, it creates an artificial phase difference of about a quarter wavelength. As the physical properties of this direct light have changed, interference with the diffracted light occurs, resulting in the phase contrast image. One disadvantage of phase-contrast microscopy is halo formation (halo-light ring).

3.1.25 Differential Interference Contrast

Superior and much more expensive is the use of interference contrast. Differences in optical density will show up as differences in relief. A nucleus within a cell will actually show up as a globule in the most often used differential interference contrast system according to Georges Nomarski. However, it has to be kept in mind that this is an optical effect, and the relief does not necessarily resemble the true shape. Contrast is very good and the condenser aperture can be used fully open, thereby reducing the depth of field and maximizing resolution.

The system consists of a special prism (Nomarski prism, Wollaston prism) in the condenser that splits light in an ordinary and an extraordinary beam. The spatial difference between the two beams is minimal (less than the maximum resolution of the objective). After passage through the specimen, the beams are reunited by a similar prism in the objective.

In a homogeneous specimen, there is no difference between the two beams, and no contrast is being generated. However, near a refractive boundary (say a nucleus within the cytoplasm), the difference between the ordinary and the extraordinary beam will generate a relief in the image. Differential interference contrast requires a polarized light source to function; two polarizing filters have to be fitted in the light path, one below the condenser (the polarizer), and the other above the objective (the analyzer).

Note: In cases where the optical design of a microscope produces an appreciable lateral separation of the two beams we have the case of classical interference microscopy, which does not result in relief images, but can nevertheless be used for the quantitative determination of mass-thicknesses of microscopic objects.

3.1.26 Interference Reflection

An additional technique using interference is interference reflection microscopy (also known as reflected interference contrast, or RIC). It relies on cell adhesion to the slide to produce an interference signal. If there is no cell attached to the glass, there will be no interference.

Interference reflection microscopy can be obtained by using the same elements used by DIC, but without the prisms. Also, the light that is being detected is reflected and not transmitted as it is when DIC is employed.

3.1.27 Fluorescence Microscopy

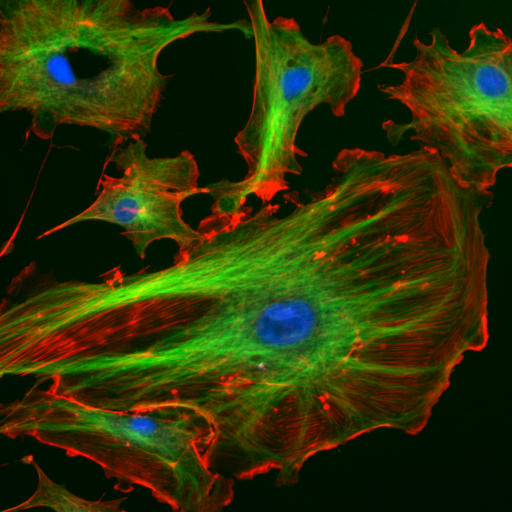

When certain compounds are illuminated with high energy light, they emit light of a lower frequency. This effect is known as fluorescence. Often specimens show their characteristic autofluorescence image, based on their chemical makeup.

This method is of critical importance in the modern life sciences, as it can be extremely sensitive, allowing the detection of single molecules. Many different fluorescent dyes can be used to stain different structures or chemical compounds. One particularly powerful method is the combination of antibodies coupled to a fluorophore as in immunostaining. Examples of commonly used fluorophores are fluorescein or rhodamine.

The antibodies can be tailor-made for a chemical compound. For example, one strategy often in use is the artificial production of proteins, based on the genetic code (DNA). These proteins can then be used to immunize rabbits, forming antibodies which bind to the protein. The antibodies are then coupled chemically to a fluorophore and used to trace the proteins in the cells under study.

Highly efficient fluorescent proteins such as the green fluorescent protein (GFP) have been developed using the molecular biology technique of gene fusion, a process that links the expression of the fluorescent compound to that of the target protein. This combined fluorescent protein is, in general, non-toxic to the organism and rarely interferes with the function of the protein under study. Genetically modified cells or organisms directly express the fluorescently tagged proteins, which enables the study of the function of the original protein in vivo.

Growth of protein crystals results in both protein and salt crystals. Both are colorless and microscopic. Recovery of the protein crystals requires imaging which can be done by the intrinsic fluorescence of the protein or by using transmission microscopy. Both methods require an ultraviolet microscope as protein absorbs light at 280 nm. Protein will also fluorescence at approximately 353 nm when excited with 280 nm light.

Since fluorescence emission differs in wavelength (color) from the excitation light, an ideal fluorescent image shows only the structure of interest that was labeled with the fluorescent dye. This high specificity led to the widespread use of fluorescence light microscopy in biomedical research. Different fluorescent dyes can be used to stain different biological structures, which can then be detected simultaneously, while still being specific due to the individual color of the dye.

To block the excitation light from reaching the observer or the detector, filter sets of high quality are needed. These typically consist of an excitation filter selecting the range of excitation wavelengths, a dichroic mirror, and an emission filter blocking the excitation light. Most fluorescence microscopes are operated in the Epi-illumination mode (illumination and detection from one side of the sample) to further decrease the amount of excitation light entering the detector.

3.1.28 Confocal Microscopy

Confocal laser scanning microscopy uses a focused laser beam (e.g. 488 nm) that is scanned across the sample to excite fluorescence in a point-by-point fashion. The emitted light is directed through a pinhole to prevent out-of-focus light from reaching the detector, typically a photomultiplier tube. The image is constructed in a computer, plotting the measured fluorescence intensities according to the position of the excitation laser. Compared to full sample illumination, confocal microscopy gives slightly higher lateral resolution and significantly improves optical sectioning (axial resolution). Confocal microscopy is, therefore, commonly used where 3D structure is important.

A subclass of confocal microscopes are spinning disc microscopes which are able to scan multiple points simultaneously across the sample. A corresponding disc with pinholes rejects out-of-focus light. The light detector in a spinning disc microscope is a digital camera, typically EM-CCD or sCMOS.

3.1.29 Two-Photon Microscopy

A two-photon microscope is also a laser-scanning microscope, but instead of UV, blue or green laser light, a pulsed infrared laser is used for excitation. Only in the tiny focus of the laser is the intensity high enough to generate fluorescence by two-photon excitation, which means that no out-of-focus fluorescence is generated, and no pinhole is necessary to clean up the image. This allows imaging deep in scattering tissue, where a confocal microscope would not be able to collect photons efficiently. Two-photon microscopes with wide-field detection are frequently used for functional imaging, e.g. calcium imaging, in brain tissue. They are marketed as Multiphoton microscopes by several companies, although the gains of using 3-photon instead of 2-photon excitation are marginal.

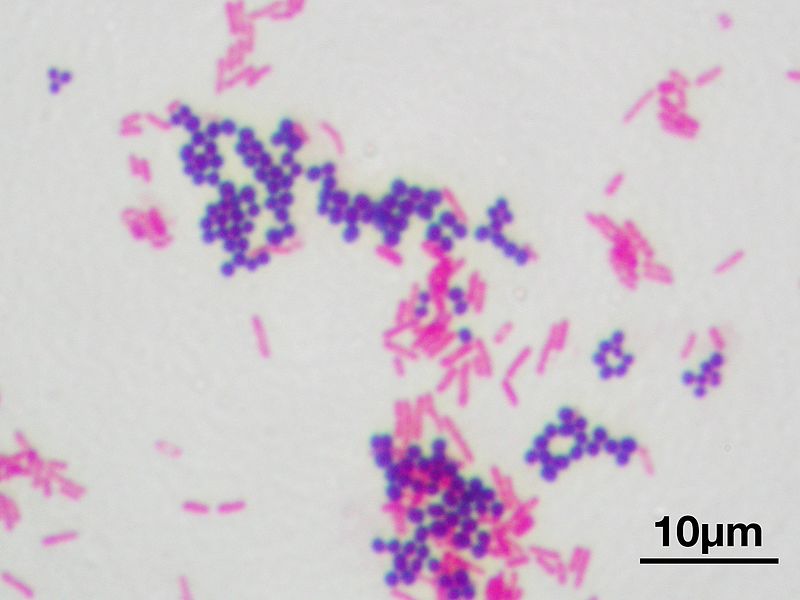

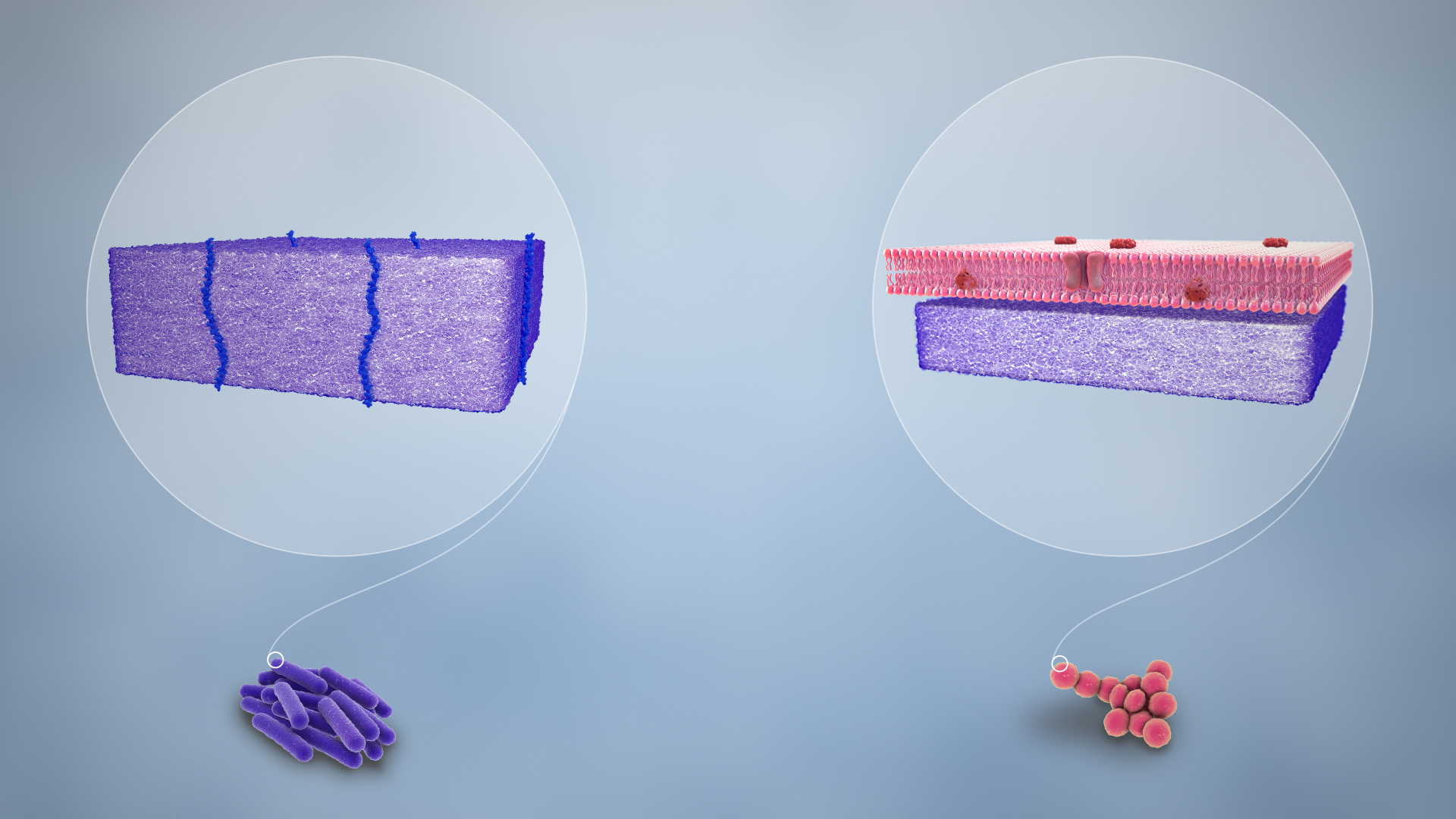

3.2 The Gram Stain

Gram stain or Gram staining, also called Gram’s method, is a method of staining used to distinguish and classify bacterial species into two large groups: gram-positive bacteria and gram-negative bacteria. The name comes from the Danish bacteriologist Hans Christian Gram, who developed the technique.

Gram staining differentiates bacteria by the chemical and physical properties of their cell walls. Gram-positive cells have a thick layer of peptidoglycan in the cell wall that retains the primary stain, crystal violet. Gram-negative cells have a thinner peptidoglycan layer that allows the crystal violet to wash out on addition of ethanol. They are stained pink or red by the counterstain, commonly safranin or fuchsine. Lugol’s iodine solution is always added after addition of crystal violet to strengthen the bonds of the stain with the cell membrane. Gram staining is almost always the first step in the preliminary identification of a bacterial organism. While Gram staining is a valuable diagnostic tool in both clinical and research settings, not all bacteria can be definitively classified by this technique. This gives rise to gram-variable and gram-indeterminate groups.

The method is named after its inventor, the Danish scientist Hans Christian Gram (1853–1938), who developed the technique while working with Carl Friedländer in the morgue of the city hospital in Berlin in 1884. Gram devised his technique not for the purpose of distinguishing one type of bacterium from another but to make bacteria more visible in stained sections of lung tissue. He published his method in 1884, and included in his short report the observation that the typhus bacillus did not retain the stain.

Gram staining is a bacteriological laboratory technique used to differentiate bacterial species into two large groups (gram-positive and gram-negative) based on the physical properties of their cell walls.[page needed] Gram staining is not used to classify archaea, formerly archaeabacteria, since these microorganisms yield widely varying responses that do not follow their phylogenetic groups.

Some organisms are gram-variable (meaning they may stain either negative or positive); some are not stained with either dye used in the Gram technique and are not seen. In a modern environmental or molecular microbiology lab, most identification is done using genetic sequences and other molecular techniques, which are far more specific and informative than differential staining.

Gram staining has been suggested to be as effective a diagnostic tool as PCR in one primary research report regarding gonorrhea.

Gram stains are performed on body fluid or biopsy when infection is suspected. Gram stains yield results much more quickly than culturing, and are especially important when infection would make an important difference in the patient’s treatment and prognosis; examples are cerebrospinal fluid for meningitis and synovial fluid for septic arthritis.

Gram-positive bacteria have a thick mesh-like cell wall made of peptidoglycan (50–90% of cell envelope), and as a result are stained purple by crystal violet, whereas gram-negative bacteria have a thinner layer (10% of cell envelope), so do not retain the purple stain and are counter-stained pink by safranin. There are four basic steps of the Gram stain:

- Applying a primary stain (crystal violet) to a heat-fixed smear of a bacterial culture. Heat fixation kills some bacteria but is mostly used to affix the bacteria to the slide so that they don’t rinse out during the staining procedure.

- The addition of iodine, which binds to crystal violet and traps it in the cell

- Rapid decolorization with ethanol or acetone

- Counterstaining with safranin. Carbol fuchsin is sometimes substituted for safranin since it more intensely stains anaerobic bacteria, but it is less commonly used as a counterstain.

Crystal violet (CV) dissociates in aqueous solutions into CV+ and chloride (Cl−) ions. These ions penetrate the cell wall of both gram-positive and gram-negative cells. The CV+ ion interacts with negatively charged components of bacterial cells and stains the cells purple.

Iodide (I− or I− 3) interacts with CV+ and forms large complexes of crystal violet and iodine (CV–I) within the inner and outer layers of the cell. Iodine is often referred to as a mordant, but is a trapping agent that prevents the removal of the CV–I complex and, therefore, colors the cell.

When a decolorizer such as alcohol or acetone is added, it interacts with the lipids of the cell membrane. A gram-negative cell loses its outer lipopolysaccharide membrane, and the inner peptidoglycan layer is left exposed. The CV–I complexes are washed from the gram-negative cell along with the outer membrane. In contrast, a gram-positive cell becomes dehydrated from an ethanol treatment. The large CV–I complexes become trapped within the gram-positive cell due to the multilayered nature of its peptidoglycan. The decolorization step is critical and must be timed correctly; the crystal violet stain is removed from both gram-positive and negative cells if the decolorizing agent is left on too long (a matter of seconds).

After decolorization, the gram-positive cell remains purple and the gram-negative cell loses its purple color. Counterstain, which is usually positively charged safranin or basic fuchsine, is applied last to give decolorized gram-negative bacteria a pink or red color. Both gram-positive bacteria and gram-negative bacteria pick up the counterstain. The counterstain, however, is unseen on gram-positive bacteria because of the darker crystal violet stain.

3.2.1 Gram-Positive Bacteria

Gram-positive bacteria generally have a single membrane (monoderm) surrounded by a thick peptidoglycan. This rule is followed by two phyla: Firmicutes (except for the classes Mollicutes and Negativicutes) and the Actinobacteria. In contrast, members of the Chloroflexi (green non-sulfur bacteria) are monoderms but possess a thin or absent (class Dehalococcoidetes) peptidoglycan and can stain negative, positive or indeterminate; members of the Deinococcus–Thermus group stain positive but are diderms with a thick peptidoglycan.[page needed]

Historically, the gram-positive forms made up the phylum Firmicutes, a name now used for the largest group. It includes many well-known genera such as Lactobacillus, Bacillus, Listeria, Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Enterococcus, and Clostridium. It has also been expanded to include the Mollicutes, bacteria such as Mycoplasma and Thermoplasma that lack cell walls and so cannot be Gram-stained, but are derived from such forms.

Some bacteria have cell walls which are particularly adept at retaining stains. These will appear positive by Gram stain even though they are not closely related to other gram-positive bacteria. These are called acid-fast bacteria, and can only be differentiated from other gram-positive bacteria by special staining procedures.

3.2.2 Gram-Negative Bacteria

Gram-negative bacteria generally possess a thin layer of peptidoglycan between two membranes (diderm). Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is the most abundant antigen on the cell surface of most Gram-negative bacteria, contributing up to 80% of the outer membrane of E. coli and Salmonella. Most bacterial phyla are gram-negative, including the cyanobacteria, green sulfur bacteria, and most Proteobacteria (exceptions being some members of the Rickettsiales and the insect-endosymbionts of the Enterobacteriales).[page needed]

3.2.3 Gram-Variable and Gram-Indeterminate Bacteria

Some bacteria, after staining with the Gram stain, yield a gram-variable pattern: a mix of pink and purple cells are seen. In cultures of Bacillus, Butyrivibrio, and Clostridium, a decrease in peptidoglycan thickness during growth coincides with an increase in the number of cells that stain gram-negative. In addition, in all bacteria stained using the Gram stain, the age of the culture may influence the results of the stain.

Gram-indeterminate bacteria do not respond predictably to Gram staining and, therefore, cannot be determined as either gram-positive or gram-negative. Examples include many species of Mycobacterium, including Mycobacterium bovis, Mycobactrium leprae and Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the latter two of which are the causative agents of leprosy and tuberculosis, respectively. Bacteria of the genus Mycoplasma lack a cell wall around their cell membranes, which means they do not stain by Gram’s method and are resistant to the antibiotics that target cell wall synthesis.

3.3 Electron Microscopy

Until the invention of sub-diffraction microscopy, the wavelength of the light limited the resolution of traditional microscopy to around 0.2 micrometers. In order to gain higher resolution, the use of an electron beam with a far smaller wavelength is used in electron microscopes.

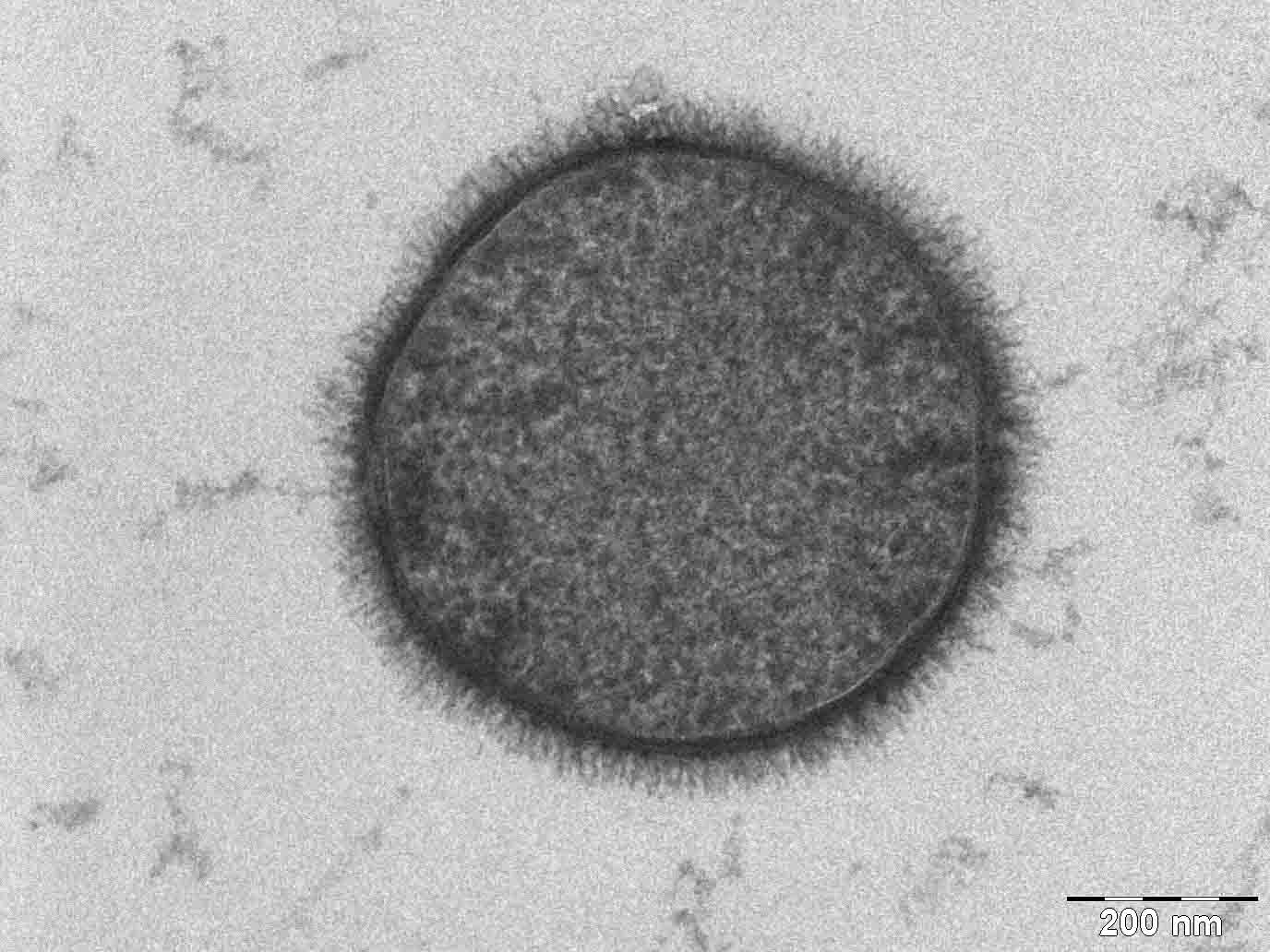

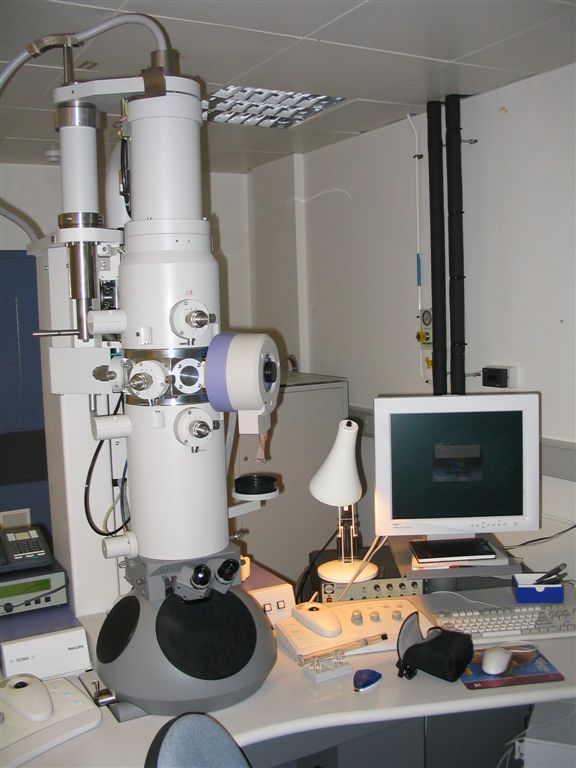

3.3.1 The Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM)

The original form of the electron microscope, the transmission electron microscope (TEM), uses a high voltage electron beam to illuminate the specimen and create an image. The electron beam is produced by an electron gun, commonly fitted with a tungsten filament cathode as the electron source. The electron beam is accelerated by an anode typically at +100 keV (40 to 400 keV) with respect to the cathode, focused by electrostatic and electromagnetic lenses, and transmitted through the specimen that is in part transparent to electrons and in part scatters them out of the beam. When it emerges from the specimen, the electron beam carries information about the structure of the specimen that is magnified by the objective lens system of the microscope. The spatial variation in this information (the “image”) may be viewed by projecting the magnified electron image onto a fluorescent viewing screen coated with a phosphor or scintillator material such as zinc sulfide. Alternatively, the image can be photographically recorded by exposing a photographic film or plate directly to the electron beam, or a high-resolution phosphor may be coupled by means of a lens optical system or a fibre optic light-guide to the sensor of a digital camera. The image detected by the digital camera may be displayed on a monitor or computer.

Figure 3.10: A modern transmission electron microscope.

The resolution of TEMs is limited primarily by spherical aberration, but a new generation of hardware correctors can reduce spherical aberration to increase the resolution in high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) to below 0.5 angstrom (50 picometres), enabling magnifications above 50 million times. The ability of HRTEM to determine the positions of atoms within materials is useful for nano-technologies research and development.

Transmission electron microscopes are often used in electron diffraction mode. The advantages of electron diffraction over X-ray crystallography are that the specimen need not be a single crystal or even a polycrystalline powder, and also that the Fourier transform reconstruction of the object’s magnified structure occurs physically and thus avoids the need for solving the phase problem faced by the X-ray crystallographers after obtaining their X-ray diffraction patterns.

One major disadvantage of the transmission electron microscope is the need for extremely thin sections of the specimens, typically about 100 nanometers. Creating these thin sections for biological and materials specimens is technically very challenging. Semiconductor thin sections can be made using a focused ion beam. Biological tissue specimens are chemically fixed, dehydrated and embedded in a polymer resin to stabilize them sufficiently to allow ultrathin sectioning. Sections of biological specimens, organic polymers, and similar materials may require staining with heavy atom labels in order to achieve the required image contrast.

3.3.2 The Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM)

The SEM produces images by probing the specimen with a focused electron beam that is scanned across a rectangular area of the specimen (raster scanning). When the electron beam interacts with the specimen, it loses energy by a variety of mechanisms. The lost energy is converted into alternative forms such as heat, emission of low-energy secondary electrons and high-energy backscattered electrons, light emission (cathodoluminescence) or X-ray emission, all of which provide signals carrying information about the properties of the specimen surface, such as its topography and composition. The image displayed by an SEM maps the varying intensity of any of these signals into the image in a position corresponding to the position of the beam on the specimen when the signal was generated. In the SEM image of an ant shown below and to the right, the image was constructed from signals produced by a secondary electron detector, the normal or conventional imaging mode in most SEMs.

Figure 3.12: SEM with opened sample chamber.

Generally, the image resolution of an SEM is lower than that of a TEM. However, because the SEM images the surface of a sample rather than its interior, the electrons do not have to travel through the sample. This reduces the need for extensive sample preparation to thin the specimen to electron transparency. The SEM is able to image bulk samples that can fit on its stage and still be maneuvered, including a height less than the working distance being used, often 4 millimeters for high-resolution images. The SEM also has a great depth of field, and so can produce images that are good representations of the three-dimensional surface shape of the sample. Another advantage of SEMs comes with environmental scanning electron microscopes (ESEM) that can produce images of good quality and resolution with hydrated samples or in low, rather than high, vacuum or under chamber gases. This facilitates imaging unfixed biological samples that are unstable in the high vacuum of conventional electron microscopes.

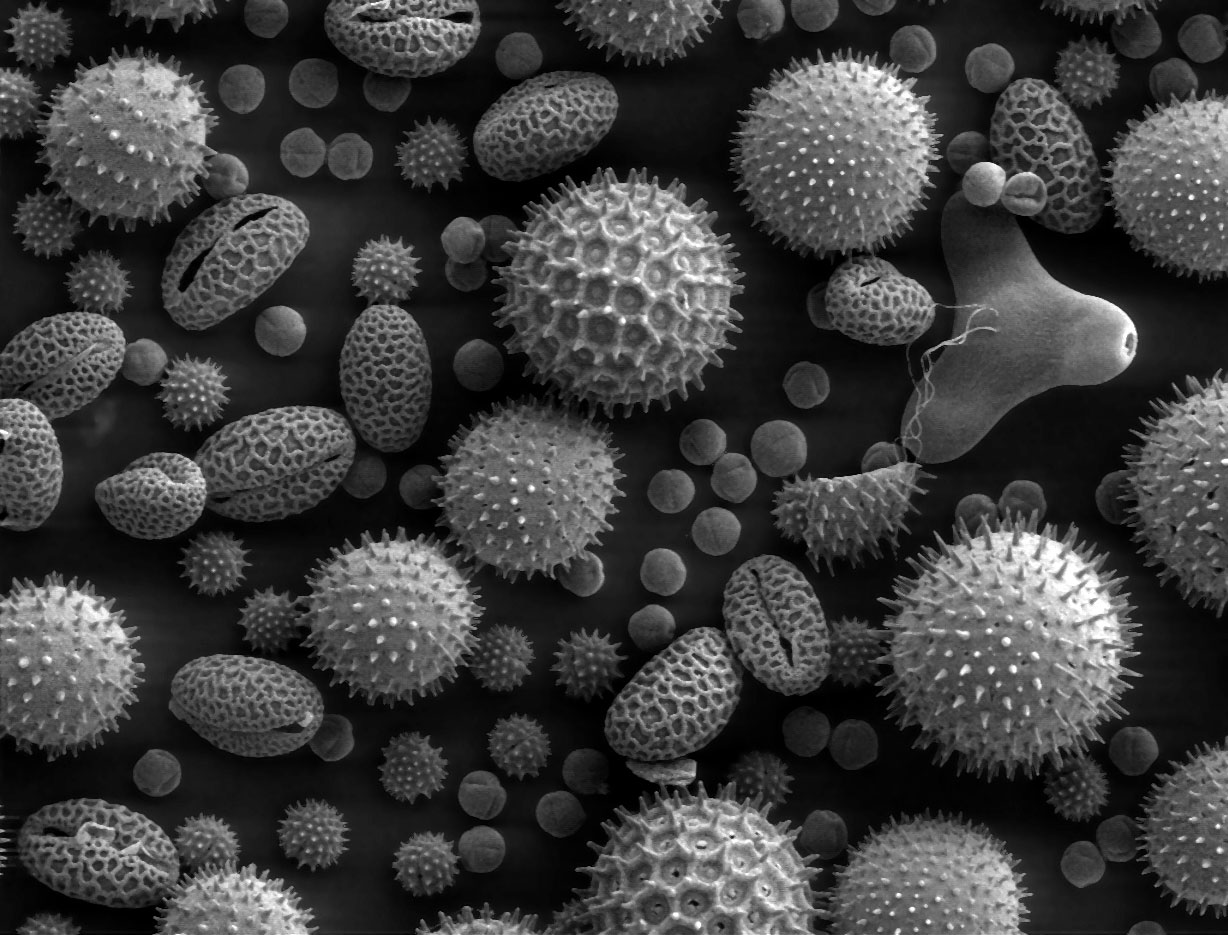

Figure 3.13: Image of pollen grains taken on a SEM shows the characteristic depth of field of SEM micrographs Pollen from a variety of common plants: sunflower (Helianthus annuus, small spiky sphericals), morning glory (Ipomoea purpurea, big sphericals with hexagonal cavities), hollyhock (Sildalcea malviflora, big spiky sphericals), lily (Lilium auratum, bean shaped), primrose (Oenothera fruticosa, tripod shaped) and castor bean (Ricinus communis, small smooth sphericals). The image is magnified some x500, so the bean shaped grain in the bottom left corner is about 50 μm long.

Electron microscopes are expensive to build and maintain, but the capital and running costs of confocal light microscope systems now overlaps with those of basic electron microscopes. Microscopes designed to achieve high resolutions must be housed in stable buildings (sometimes underground) with special services such as magnetic field canceling systems.

The samples largely have to be viewed in vacuum, as the molecules that make up air would scatter the electrons. An exception is liquid-phase electron microscopy using either a closed liquid cell or an environmental chamber, for example, in the environmental scanning electron microscope, which allows hydrated samples to be viewed in a low-pressure (up to 20 Torr or 2.7 kPa) wet environment. Various techniques for in situ electron microscopy of gaseous samples have been developed as well.

Scanning electron microscopes operating in conventional high-vacuum mode usually image conductive specimens; therefore non-conductive materials require conductive coating (gold/palladium alloy, carbon, osmium, etc.). The low-voltage mode of modern microscopes makes possible the observation of non-conductive specimens without coating. Non-conductive materials can be imaged also by a variable pressure (or environmental) scanning electron microscope.

Small, stable specimens such as carbon nanotubes, diatom frustules and small mineral crystals (asbestos fibres, for example) require no special treatment before being examined in the electron microscope. Samples of hydrated materials, including almost all biological specimens have to be prepared in various ways to stabilize them, reduce their thickness (ultrathin sectioning) and increase their electron optical contrast (staining). These processes may result in artifacts, but these can usually be identified by comparing the results obtained by using radically different specimen preparation methods. Since the 1980s, analysis of cryofixed, vitrified specimens has also become increasingly used by scientists, further confirming the validity of this technique.

3.4 Microbiological Culture

A microbiological culture, or microbial culture, is a method of multiplying microbial organisms by letting them reproduce in predetermined culture medium under controlled laboratory conditions. Microbial cultures are foundational and basic diagnostic methods used as a research tool in molecular biology.

Microbial cultures are used to determine the type of organism, its abundance in the sample being tested, or both. It is one of the primary diagnostic methods of microbiology and used as a tool to determine the cause of infectious disease by letting the agent multiply in a predetermined medium. For example, a throat culture is taken by scraping the lining of tissue in the back of the throat and blotting the sample into a medium to be able to screen for harmful microorganisms, such as Streptococcus pyogenes, the causative agent of strep throat. Furthermore, the term culture is more generally used informally to refer to “selectively growing” a specific kind of microorganism in the lab.

It is often essential to isolate a pure culture of microorganisms. A pure (or axenic) culture is a population of cells or multicellular organisms growing in the absence of other species or types. A pure culture may originate from a single cell or single organism, in which case the cells are genetic clones of one another. For the purpose of gelling the microbial culture, the medium of agarose gel (agar) is used. Agar is a gelatinous substance derived from seaweed. A cheap substitute for agar is guar gum, which can be used for the isolation and maintenance of thermophiles.

There are several types of bacterial culture methods that are selected based on the agent being cultured and the downstream use.

3.4.1 Broth cultures

One method of bacterial culture is liquid culture, in which the desired bacteria are suspended in a liquid nutrient medium, such as Luria Broth, in an upright flask. This allows a scientist to grow up large amounts of bacteria for a variety of downstream applications.

Liquid cultures are ideal for preparation of an antimicrobial assay in which the experimenter inoculates liquid broth with bacteria and lets it grow overnight (they may use a shaker for uniform growth). Then they would take aliquots of the sample to test for the antimicrobial activity of a specific drug or protein (antimicrobial peptides).

As an alternative, the microbiologist may decide to use static liquid cultures. These cultures are not shaken and they provide the microbes with an oxygen gradient.

3.4.2 Agar Plates

An agar plate is a Petri dish that contains a growth medium solidified with agar, used to culture microorganisms. Sometimes selective compounds are added to influence growth, such as antibiotics.

There are a variety of additives that can be added to agar before it is poured into a plate and allowed to solidify. Some types of bacteria can only grow in the presence of certain additives. This can also be used when creating engineered strains of bacteria that contain an antibiotic-resistance gene. When the selected antibiotic is added to the agar, only bacterial cells containing the gene insert conferring resistance will be able to grow. This allows the researcher to select only the colonies that were successfully transformed.

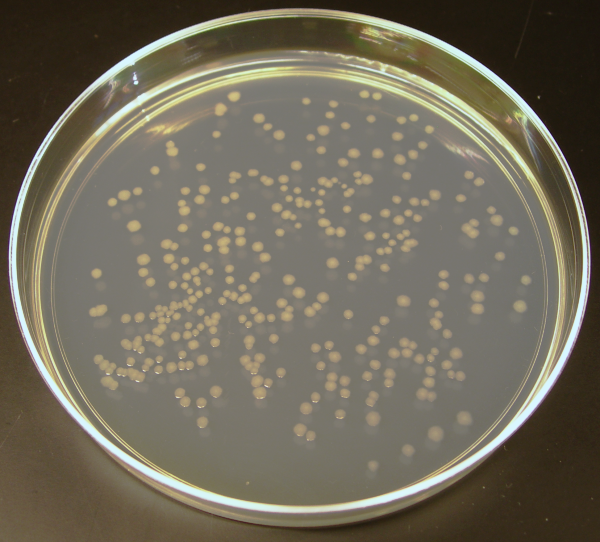

Individual microorganisms placed on the plate will grow into individual colonies, each a clone genetically identical to the individual ancestor organism (except for the low, unavoidable rate of mutation). Thus, the plate can be used either to estimate the concentration of organisms in a liquid culture or a suitable dilution of that culture using a colony counter, or to generate genetically pure cultures from a mixed culture of genetically different organisms.

Figure 3.15: An agar culture of E. coli colonies.

Several methods are available to plate out cells. One technique is known as “streaking”. In this technique, a drop of the culture on the end of a thin, sterile loop of wire, sometimes known as an inoculator or inoculation loop, is streaked across the surface of the agar leaving organisms behind, a higher number at the beginning of the streak and a lower number at the end. At some point during a successful “streak”, the number of organisms deposited will be such that distinct individual colonies will grow in that area which may be removed for further culturing, using another sterile loop. It is crucial to work sterile to prevent contamination on the plates.

Cells in a centrally place drop can also be evenvly spread across the surface of and agar plate using a cell spreader.

Figure 3.17: A set of plate spreaders (Drigalski’s spatulas).

Another way of plating organisms, next to streaking, on agar plates is the spot analysis. This type of analysis is often used to check the viability of cells and performed with pinners (often also called froggers). A third used technique is the use of sterile glass beads to plate out cells. In this technique cells are grown in a liquid culture of which a small volume is pipetted on the agar plate and then spread out with the beads. Replica plating is another technique in order to plate out cells on agar plates. These four techniques are the most common, but others are also possible. It is crucial to work in a sterile manner in order to prevent contamination on the agar plates. Plating is thus often done in a laminar flow cabinet or on the working bench next to a bunsen burner.

In 1881, Fanny Hesse, who was working as a technician for her husband Walther Hesse in the laboratory of Robert Koch, suggested agar as an effective setting agent, since it had been commonplace in jam making for some time.

Like other growth media, the formulations of agar used in plates may be classified as either “defined” or “undefined”; a defined medium is synthesized from individual chemicals required by the organism so the exact molecular composition is known, whereas an undefined medium is made from natural products such as yeast extract, where the precise composition is unknown.

Agar plates may be formulated as either permissive, with the intent of allowing the growth of whatever organisms are present, or restrictive or selective, with the intent of only allowing growth a particular subset of those organisms. This may take the form of a nutritional requirement, for instance providing a particular compound such as lactose as the only source of carbon and thereby selecting only organisms which can metabolize that compound, or by including a particular antibiotic or other substance to select only organisms which are resistant to that substance. This correlates to some degree with defined and undefined media; undefined media, made from natural products and containing an unknown combination of very many organic molecules, is typically more permissive in terms of supplying the needs of a wider variety of organisms, while defined media can be precisely tailored to select organisms with specific properties.

Agar plates may also be indicator plates, in which the organisms are not selected on the basis of growth, but are instead distinguished by a color change in some colonies, typically caused by the action of an enzyme on some compound added to the medium.

The plates are incubated for 12 hours up to several days depending on the test that is performed.

Some commonly used agar plate types are:

3.4.3 Blood Agar Plate

Blood agar plates (BAPs) contain mammalian blood (usually sheep or horse), typically at a concentration of 5–10%. BAPs are enriched, differential media used to isolate fastidious organisms and detect hemolytic activity. β-Hemolytic activity will show lysis and complete digestion of red blood cell contents surrounding a colony. Examples include Streptococcus haemolyticus. α-Hemolysis will only cause partial lysis of the red blood cells (the cell membrane is left intact) and will appear green or brown, due to the conversion of hemoglobin to methemoglobin. An example of this would be Streptococcus viridans. γ-Hemolysis (or nonhemolytic) is the term referring to a lack of hemolytic activity. BAPs also contain meat extract, tryptone, sodium chloride, and agar.

3.4.4 Chocolate Agar

Chocolate agar a type of blood agar plate in which the blood cells have been lysed by heating the cells to 80 °C. It is used for growing fastidious respiratory bacteria, such as Haemophilus influenzae. No chocolate is actually contained in the plate; it is named for the coloration only.

3.4.5 Stab Cultures

Stab cultures are similar to agar plates, but are formed by solid agar in a test tube. Bacteria is introduced via an inoculation needle or a pipette tip being stabbed into the center of the agar. Bacteria grow in the punctured area. Stab cultures are most commonly used for short-term storage or shipment of cultures.

3.5 Culture Collections

Microbial culture collections focus on the acquisition, authentication, production, preservation, catalogueing and distribution of viable cultures of standard reference microorganisms, cell lines and other materials for research in microbial systematics. Culture collection are also repositories of type strains.

3.6 Growth Medium

A growth medium or culture medium is a solid, liquid, or semi-solid designed to support the growth of a population of microorganisms or cells via the process of cell proliferation or small plants like the moss Physcomitrella patens. Different types of media are used for growing different types of cells.

The two major types of growth media are those used for cell culture, which use specific cell types derived from plants or animals, and those used for microbiological culture, which are used for growing microorganisms such as bacteria or fungi. The most common growth media for microorganisms are nutrient broths and agar plates; specialized media are sometimes required for microorganism and cell culture growth. Some organisms, termed fastidious organisms, require specialized environments due to complex nutritional requirements. Viruses, for example, are obligate intracellular parasites and require a growth medium containing living cells.

The most common growth media for microorganisms are nutrient broths (liquid nutrient medium) or lysogeny broth medium. Liquid media are often mixed with agar and poured via a sterile media dispenser into Petri dishes to solidify. These agar plates provide a solid medium on which microbes may be cultured. They remain solid, as very few bacteria are able to decompose agar (the exception being some species in the genera: Cytophaga, Flavobacterium, Bacillus, Pseudomonas, and Alcaligenes). Bacteria grown in liquid cultures often form colloidal suspensions.

The difference between growth media used for cell culture and those used for microbiological culture is that cells derived from whole organisms and grown in culture often cannot grow without the addition of, for instance, hormones or growth factors which usually occur in vivo. In the case of animal cells, this difficulty is often addressed by the addition of blood serum or a synthetic serum replacement to the medium. In the case of microorganisms, no such limitations exist, as they are often unicellular organisms. One other major difference is that animal cells in culture are often grown on a flat surface to which they attach, and the medium is provided in a liquid form, which covers the cells. In contrast, bacteria such as Escherichia coli may be grown on solid or in liquid media.

An important distinction between growth media types is that of defined versus undefined media. A defined medium will have known quantities of all ingredients. For microorganisms, they consist of providing trace elements and vitamins required by the microbe and especially defined carbon and nitrogen sources. Glucose or glycerol are often used as carbon sources, and ammonium salts or nitrates as inorganic nitrogen sources. An undefined medium has some complex ingredients, such as yeast extract or casein hydrolysate, which consist of a mixture of many chemical species in unknown proportions. Undefined media are sometimes chosen based on price and sometimes by necessity – some microorganisms have never been cultured on defined media.

A good example of a growth medium is the wort used to make beer. The wort contains all the nutrients required for yeast growth, and under anaerobic conditions, alcohol is produced. When the fermentation process is complete, the combination of medium and dormant microbes, now beer, is ready for consumption. The main types are

- cultural media

- minimal media

- selective media

- differential media

- transport media

- indicator media

3.6.1 Culture Media

Culture media contain all the elements that most bacteria need for growth and are not selective, so they are used for the general cultivation and maintenance of bacteria kept in laboratory culture collections. An undefined medium (also known as a basal or complex medium) contains:

- a carbon source such as glucose

- water

- various salts

- a source of amino acids and nitrogen (e.g. beef, yeast extract)

This is an undefined medium because the amino-acid source contains a variety of compounds; the exact composition is unknown.

A defined medium (also known as chemically defined medium or synthetic medium) is a medium in which

- all the chemicals used are known

- no yeast, animal, or plant tissue is present

Examples of nutrient media:

- nutrient agar

- plate count agar

- trypticase soy agar

3.6.2 Minimal Media

A defined medium that has just enough ingredients to support growth is called a “minimal medium”. The number of ingredients that must be added to a minimal medium varies enormously depending on which microorganism is being grown. Minimal media are those that contain the minimum nutrients possible for colony growth, generally without the presence of amino acids, and are often used by microbiologists and geneticists to grow “wild-type” microorganisms. Minimal media can also be used to select for or against recombinants or exconjugants.

Minimal medium typically contains:

- a carbon source, which may be a sugar such as glucose, or a less energy-rich source such as succinate

- various salts, which may vary among bacteria species and growing conditions; these generally provide essential elements such as magnesium, nitrogen, phosphorus, and sulfur to allow the bacteria to synthesize protein and nucleic acids

- water

Supplementary minimal media are minimal media that also contains a single selected agent, usually an amino acid or a sugar. This supplementation allows for the culturing of specific lines of auxotrophic recombinants.

3.6.3 Selective Media

Selective media are used for the growth of only selected microorganisms. For example, if a microorganism is resistant to a certain antibiotic, such as ampicillin or tetracycline, then that antibiotic can be added to the medium to prevent other cells, which do not possess the resistance, from growing. Media lacking an amino acid such as proline in conjunction with E. coli unable to synthesize it were commonly used by geneticists before the emergence of genomics to map bacterial chromosomes.

Selective growth media are also used in cell culture to ensure the survival or proliferation of cells with certain properties, such as antibiotic resistance or the ability to synthesize a certain metabolite. Normally, the presence of a specific gene or an allele of a gene confers upon the cell the ability to grow in the selective medium. In such cases, the gene is termed a marker.

Selective growth media for eukaryotic cells commonly contain neomycin to select cells that have been successfully transfected with a plasmid carrying the neomycin resistance gene as a marker. Gancyclovir is an exception to the rule, as it is used to specifically kill cells that carry its respective marker, the Herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase.

Examples of selective media:

- Eosin methylene blue contains dyes that are toxic for Gram-positive bacteria. It is the selective and differential medium for coliforms.

- YM (yeast extract, malt extract agar) has a low pH, deterring bacterial growth.

- MacConkey agar is for Gram-negative bacteria.

- Hektoen enteric agar is selective for Gram-negative bacteria.

- HIS-selective medium is a type cell culture medium that lacks the amino acid histidine.

- Mannitol salt agar is selective for gram-positive bacteria and differential for mannitol.

- Xylose lysine deoxycholate is selective for Gram-negative bacteria.

- Buffered charcoal yeast extract agar is selective for certain gram-negative bacteria, especially Legionella pneumophila.

- Baird–Parker agar is for gram-positive staphylococci.

- Sabouraud’s agar is selective to certain fungi due to its low pH (5.6) and high glucose concentration (3–4%).

- DRBC (dichloran rose bengal chloramphenicol agar) is a selective medium for the enumeration of moulds and yeasts in foods. Dichloran and rose bengal restrict the growth of mould colonies, preventing overgrowth of luxuriant species and assisting accurate counting of colonies.

3.6.4 Differential Media

Differential or indicator media distinguish one microorganism type from another growing on the same medium. This type of media uses the biochemical characteristics of a microorganism growing in the presence of specific nutrients or indicators (such as neutral red, phenol red, eosin y, or methylene blue) added to the medium to visibly indicate the defining characteristics of a microorganism. These media are used for the detection of microorganisms and by molecular biologists to detect recombinant strains of bacteria.

Examples of differential media:

- Blood agar (used in strep tests) contains bovine heart blood that becomes transparent in the presence of β-hemolytic organisms such as Streptococcus pyogenes and Staphylococcus aureus.

- Eosin methylene blue is differential for lactose fermentation.

- Granada medium is selective and differential for Streptococcus agalactiae (group B streptococcus) which grows as distinctive red colonies in this medium.

- MacConkey agar is differential for lactose fermentation.

- Mannitol salt agar is differential for mannitol fermentation.

- X-gal plates are differential for lac operon mutants.

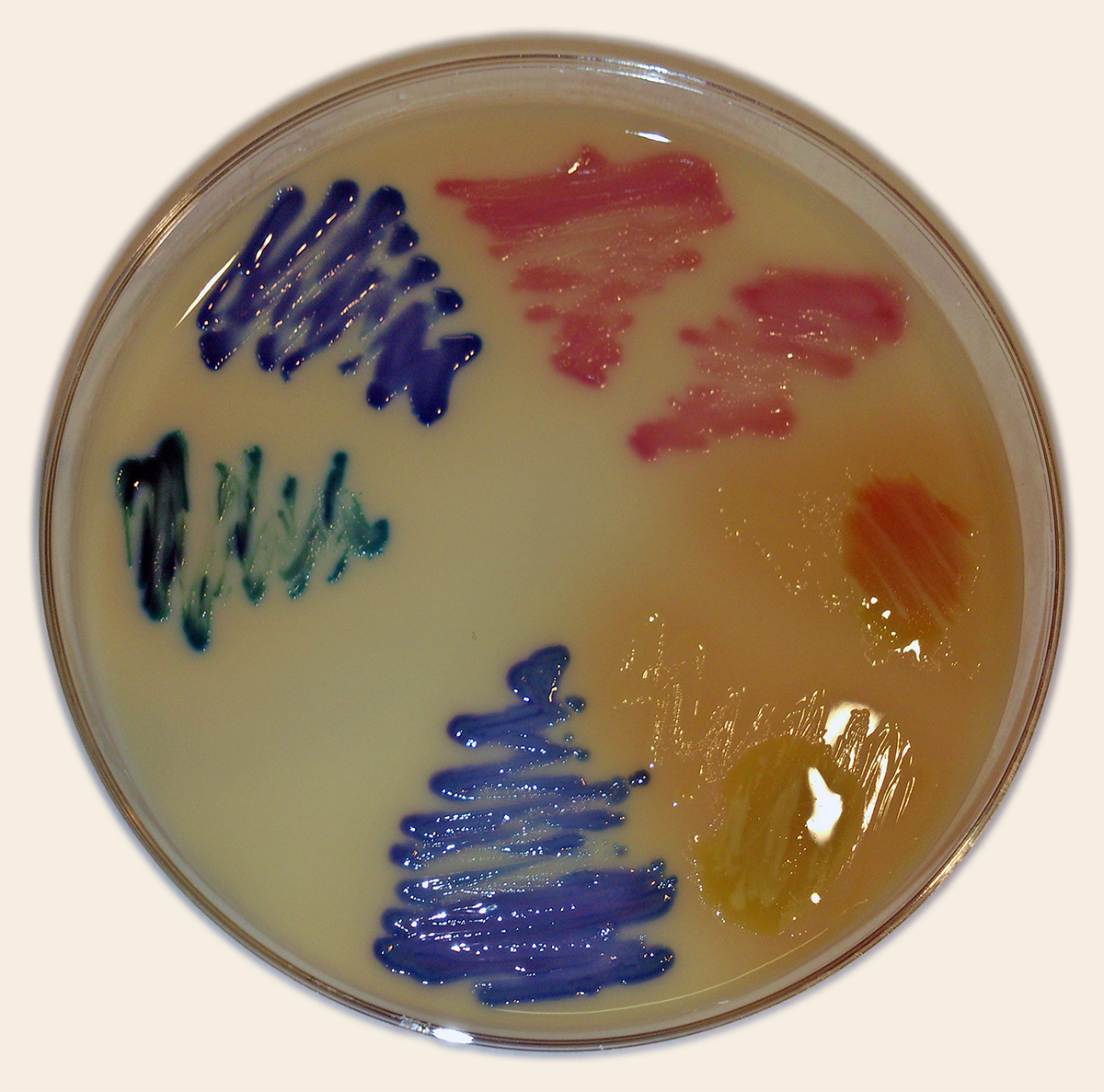

Figure 3.20: UTI Agar is a chromogenic medium for identification and differentiation of main microorganisms that cause urinary tract infections (UTIs). On the agar plate you can see the following colonies: Pink - E. coli; Blue-green/turquoise - Enterococcus spp.; Dark blue - Klebsiella spp.; Light brown with a red dot - Proteus mirabilis; Light brown - Proteus spp.

3.6.5 Transport Media

Transport media should fulfill these criteria:

- Temporary storage of specimens being transported to the laboratory for cultivation

- Maintain the viability of all organisms in the specimen without altering their concentration

- Contain only buffers and salt

- Lack of carbon, nitrogen, and organic growth factors so as to prevent microbial multiplication

- Transport media used in the isolation of anaerobes must be free of molecular oxygen.

Examples of transport media:

- Thioglycolate broth is for strict anaerobes.

- Stuart transport medium is a non-nutrient soft agar gel containing a reducing agent to prevent oxidation, and charcoal to neutralize.

- Certain bacterial inhibitors are used for gonococci, and buffered glycerol saline for enteric bacilli.

- Venkataraman Ramakrishna (VR) medium is used for V. cholerae.dd

3.6.6 Enriched Media

Enriched media contain the nutrients required to support the growth of a wide variety of organisms, including some of the more fastidious ones. They are commonly used to harvest as many different types of microbes as are present in the specimen. Blood agar is an enriched medium in which nutritionally rich whole blood supplements the basic nutrients. Chocolate agar is enriched with heat-treated blood (40–45 °C or 104–113 °F), which turns brown and gives the medium the color for which it is named.

.jpg)