8 Eukaryotic chromosome structure

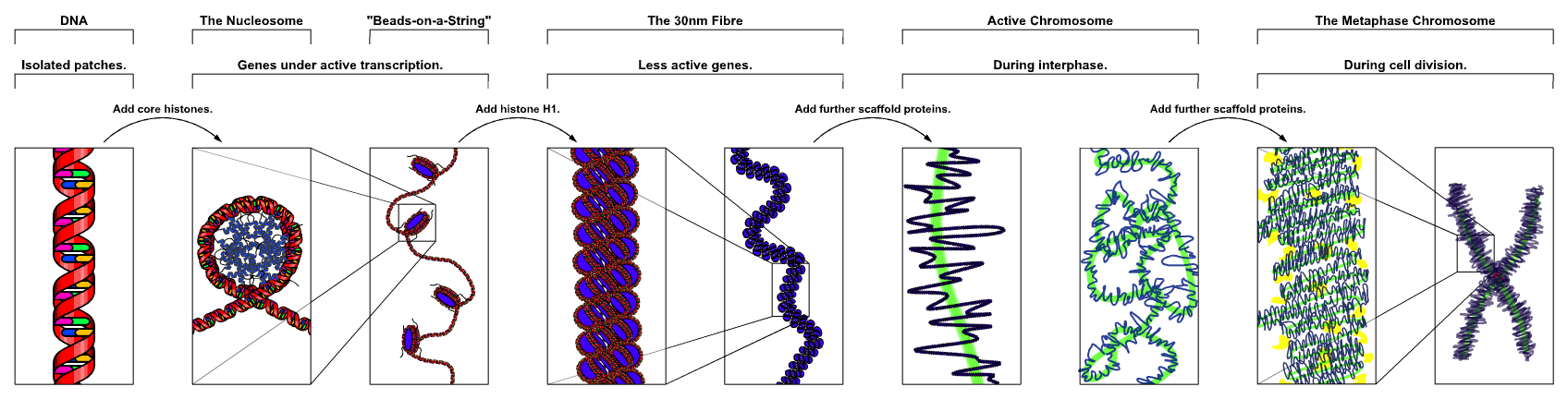

Eukaryotic chromosome structure refers to the levels of packaging from the raw DNA molecules to the chromosomal structures seen during metaphase in mitosis or meiosis. Chromosomes contain long strands of DNA containing genetic information. Compared to prokaryotic chromosomes, eukaryotic chromosomes are much larger in size and are linear chromosomes. Eukaryotic chromosomes are also stored in the nucleus of the cell, while chromosomes of prokaryotic cells are not stored in a nucleus.

Some of the first sientists to recognize the structures now known as chromosomes were Matthias Jakob Schleiden, Rudolf Virchow, and Otto Bütschli. The term was coined by Heinrich Wilhelm Gottfried von Waldeyer-Hartz, referring to the term chromatin, that was introduced by Walther Flemming.

In humans, roughly 3.2 billion nucleotides are spread out over 23 different chromosomes. Each chromosome consists of long linear DNA molecule associated with proteins that fold and pack the fine thread of DNA into a more compact structure.

8.1 Nucleosome

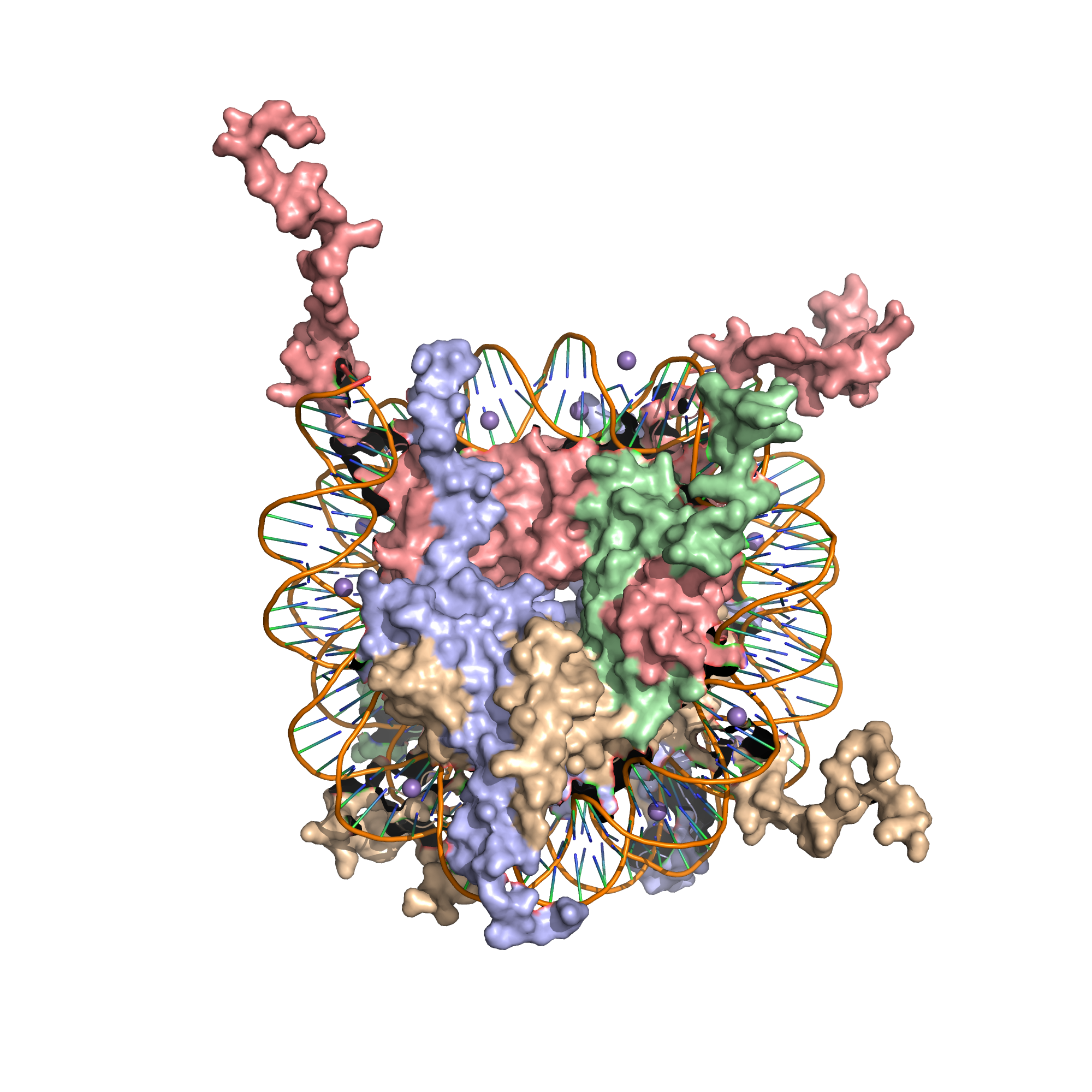

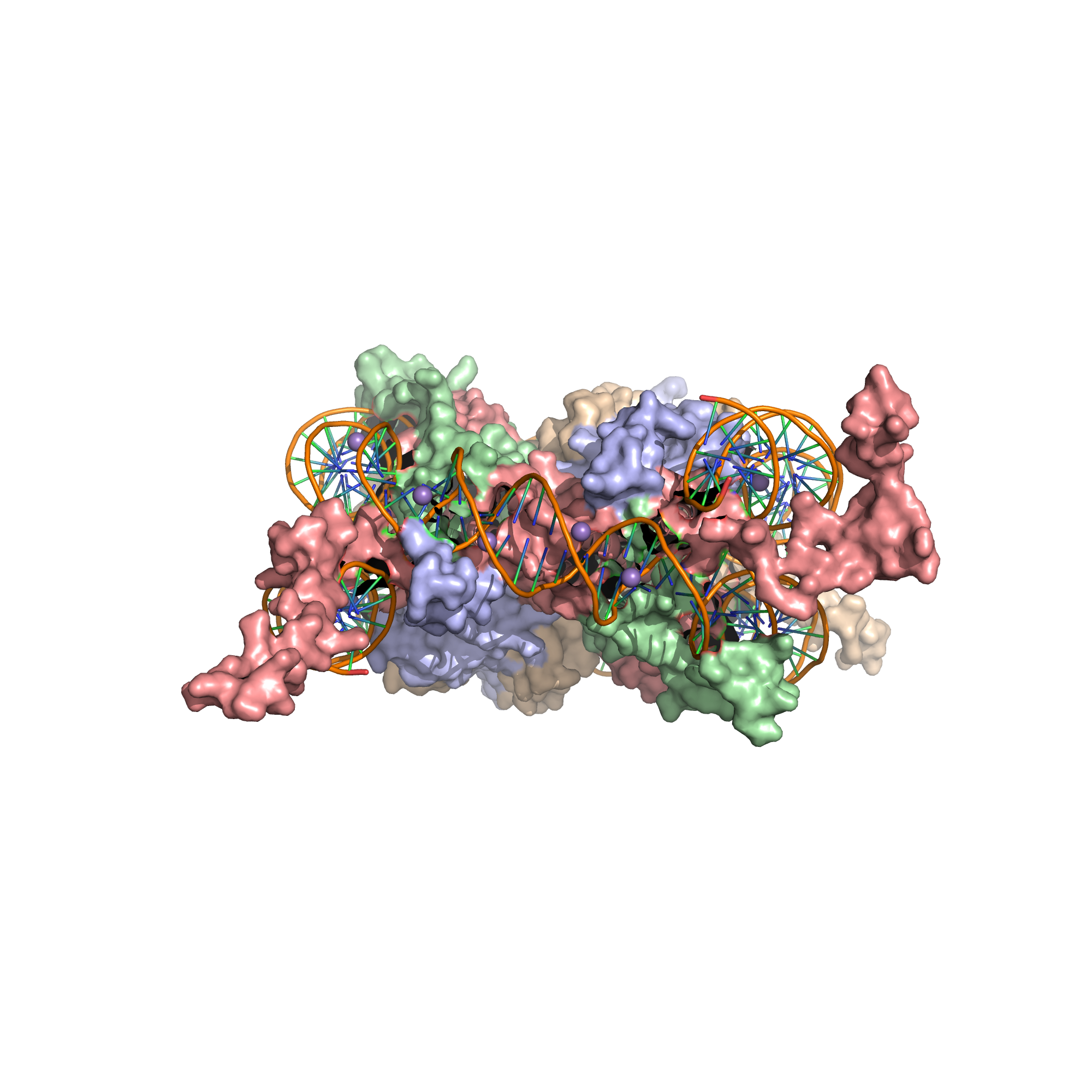

A nucleosome is the basic structural unit of DNA packaging in eukaryotes. The structure of a nucleosome consists of a segment of DNA wound around eight histone proteins and resembles thread wrapped around a spool (Figure 8.1).

Figure 8.1: X-Ray crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle consisting of H2A (lightblue), H2B (wheat), H3 (salmon) and H4 (palegreen) core histones, and DNA. Structure of the nucleosome core particle, NCP147, at 1.9 A resolution. Top: view is from the top through the superhelical axis. Bottom: side view.

DNA must be compacted into nucleosomes to fit within the cell nucleus. In addition to nucleosome wrapping, eukaryotic chromatin is further compacted by being folded into a series of more complex structures, eventually forming a chromosome.

Nucleosomes are thought to carry epigenetically inherited information in the form of covalent modifications of their core histones. Nucleosome positions in the genome are not random, and it is important to know where each nucleosome is located because this determines the accessibility of the DNA to regulatory proteins.

Nucleosomes were first observed as particles in the electron microscope in 1974.

The nucleosome core particle consists of approximately 146 base pairs (bp) of DNA wrapped in 1.67 left-handed superhelical turns around a histone octamer, consisting of 2 copies each of the core histones H2A, H2B, H3, and H4. Core particles are connected by stretches of linker DNA, which can be up to about 80 bp long. Technically, a nucleosome is defined as the core particle plus one of these linker regions; however the word is often synonymous with the core particle.

In general, genes that are active have less bound histone, while inactive genes are highly associated with histones during interphase. It also appears that the structure of histones has been evolutionarily conserved. All histones have a highly positively charged N-terminus with many lysine and arginine residues.

The core histone proteins contains a characteristic structural motif termed the “histone fold”, which consists of three alpha-helices (α1-3) separated by two loops (L1-2). In solution, the histones form H2A-H2B heterodimers and H3-H4 heterotetramers. Histones dimerise about their long α2 helices in an anti-parallel orientation, and, in the case of H3 and H4, two such dimers form a 4-helix bundle stabilised by extensive H3-H3’ interaction. The H2A/H2B dimer binds onto the H3/H4 tetramer due to interactions between H4 and H2B, which include the formation of a hydrophobic cluster. The histone octamer is formed by a central H3/H4 tetramer sandwiched between two H2A/H2B dimers. Due to the highly basic charge of all four core histones, the histone octamer is stable only in the presence of DNA or very high salt concentrations.

8.2 Higher order structure of DNA

The organization of the DNA that is achieved by the nucleosome cannot fully explain the packaging of DNA observed in the cell nucleus. Further compaction of chromatin into the cell nucleus is necessary, but is not yet well understood. The current understanding is that repeating nucleosomes with intervening “linker” DNA form a 10-nm-fiber, described as “beads on a string”, and have a packing ratio of about five to ten. A chain of nucleosomes can be arranged in a 30 nm fiber, a compacted structure with a packing ratio of ~50 and whose formation is dependent on the presence of the H1 histone.

A crystal structure of a tetranucleosome has been presented and used to build up a proposed structure of the 30 nm fiber as a two-start helix. There is still a certain amount of contention regarding this model, as it is incompatible with recent electron microscopy data. Beyond this, the structure of chromatin is poorly understood, but it is classically suggested that the 30 nm fiber is arranged into loops along a central protein scaffold to form transcriptionally active euchromatin. Further compaction leads to transcriptionally inactive heterochromatin.

Although the nucleosome is a very stable protein-DNA complex, it is not static and has been shown to undergo a number of different structural re-arrangements including nucleosome sliding and DNA site exposure. Depending on the context, nucleosomes can inhibit or facilitate transcription factor binding. Nucleosome positions are controlled by three major contributions: First, the intrinsic binding affinity of the histone octamer depends on the DNA sequence. Second, the nucleosome can be displaced or recruited by the competitive or cooperative binding of other protein factors. Third, the nucleosome may be actively translocated by ATP-dependent remodeling complexes.

Promoters of active genes have nucleosome free regions (NFR). This allows for promoter DNA accessibility to various proteins, such as transcription factors. Nucleosome free region typically spans for 200 nucleotides in S. cerevisae Well-positioned nucleosomes form boundaries of NFR. These nucleosomes are called +1-nucleosome and −1-nucleosome and are located at canonical distances downstream and upstream, respectively, from transcription start site. +1-nucleosome and several downstream nucleosomes also tend to incorporate H2A.Z histone variant.

8.3 Modulating nucleosome structure

Eukaryotic genomes are ubiquitously associated into chromatin; however, cells must spatially and temporally regulate specific loci independently of bulk chromatin. In order to achieve the high level of control required to co-ordinate nuclear processes such as DNA replication, repair, and transcription, cells have developed a variety of means to locally and specifically modulate chromatin structure and function. This can involve covalent modification of histones, the incorporation of histone variants, and non-covalent remodelling by ATP-dependent remodeling enzymes.

8.4 Histone post-translational modifications

Since they were discovered in the mid-1960s, histone modifications have been predicted to affect transcription. Some modifications have been shown to be correlated with gene silencing; others seem to be correlated with gene activation. Common modifications include acetylation, methylation, or ubiquitination of lysine; methylation of arginine; and phosphorylation of serine. The information stored in this way is considered epigenetic, since it is not encoded in the DNA but is still inherited to daughter cells. The maintenance of a repressed or activated status of a gene is often necessary for cellular differentiation.

8.5 Histones

Five major families of histones exist: H1/H5, H2A, H2B, H3, and H4. Histones H2A, H2B, H3 and H4 are known as the core histones, while histones H1/H5 are known as the linker histones.

Histones are subdivided into canonical replication-dependent histones that are expressed during the S-phase of cell cycle and replication-independent histone variants, expressed during the whole cell cycle. In animals, genes encoding canonical histones are typically clustered along the chromosome, lack introns and use a stem loop structure at the 3’ end instead of a polyA tail. Genes encoding histone variants are usually not clustered, have introns and their mRNAs are regulated with polyA tails. Complex multicellular organisms typically have a higher number of histone variants providing a variety of different functions. Recent data are accumulating about the roles of diverse histone variants highlighting the functional links between variants and the delicate regulation of organism development.

Histones were discovered in 1884 by Albrecht Kossel. The word “histone” dates from the late 19th century and is derived from the German word “Histon”, a word itself of uncertain origin.

In the 1960s, Vincent Allfrey and Alfred Mirsky had suggested, based on their analyses of histones, that acetylation and methylation of histones could provide a transcriptional control mechanism, but did not have available the kind of detailed analysis that later investigators were able to conduct to show how such regulation could be gene-specific. Until the early 1990s, histones were dismissed by most as inert packing material for eukaryotic nuclear DNA.

During the 1980s, Yahli Lorch and Roger Kornberg showed that a nucleosome on a core promoter prevents the initiation of transcription in vitro, and Michael Grunstein demonstrated that histones repress transcription in vivo, leading to the idea of the nucleosome as a general gene repressor. Relief from repression is believed to involve both histone modification and the action of chromatin-remodeling complexes.

Histones are believed to have evolved from ribosomal proteins with which they share much in common, both being short and basic proteins.

Histones undergo posttranslational modifications that alter their interaction with DNA and nuclear proteins. The H3 and H4 histones have long tails protruding from the nucleosome, which can be covalently modified at several places. Modifications of the tail include methylation, acetylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitination, SUMOylation, citrullination, and ADP-ribosylation. The core of the histones H2A and H2B can also be modified. Combinations of modifications are thought to constitute a code, the so-called “histone code”. Histone modifications act in diverse biological processes such as gene regulation, DNA repair, chromosome condensation (mitosis) and spermatogenesis (meiosis).

The common nomenclature of histone modifications is:

- The name of the histone (e.g., H3)

- The single-letter amino acid abbreviation (e.g., K for Lysine) and the amino acid position in the protein

- The type of modification (Me: methyl, P: phosphate, Ac: acetyl, Ub: ubiquitin)

- The number of modifications (only Me is known to occur in more than one copy per residue. 1, 2 or 3 is mono-, di- or tri-methylation)

So H3K4me1 denotes the monomethylation of the 4th residue (a lysine) from the start (i.e., the N-terminal) of the H3 protein.

8.6 Functions of histone modifications

A huge catalogue of histone modifications have been described, but a functional understanding of most is still lacking. Collectively, it is thought that histone modifications may underlie a histone code, whereby combinations of histone modifications have specific meanings. However, most functional data concerns individual prominent histone modifications that are biochemically amenable to detailed study.

8.7 Chemistry of histone modifications

8.7.1 Lysine methylation

The addition of one, two, or many methyl groups to lysine has little effect on the chemistry of the histone; methylation leaves the charge of the lysine intact and adds a minimal number of atoms so steric interactions are mostly unaffected. However, proteins containing Tudor, chromo or PHD domains, amongst others, can recognise lysine methylation with exquisite sensitivity and differentiate mono, di and tri-methyl lysine, to the extent that, for some lysines (e.g.: H4K20) mono, di and tri-methylation appear to have different meanings. Because of this, lysine methylation tends to be a very informative mark and dominates the known histone modification functions.

8.7.2 Arginine methylation

What was said above of the chemistry of lysine methylation also applies to arginine methylation, and some protein domains—e.g., Tudor domains—can be specific for methyl arginine instead of methyl lysine. Arginine is known to be mono- or di-methylated, and methylation can be symmetric or asymmetric, potentially with different meanings.

8.7.3 Lysine acetylation

Addition of an acetyl group has a major chemical effect on lysine as it neutralises the positive charge. This reduces electrostatic attraction between the histone and the negatively charged DNA backbone, loosening the chromatin structure; highly acetylated histones form more accessible chromatin and tend to be associated with active transcription. Lysine acetylation appears to be less precise in meaning than methylation, in that histone acetyltransferases tend to act on more than one lysine; presumably this reflects the need to alter multiple lysines to have a significant effect on chromatin structure. The modification includes H3K27ac.

8.7.4 Serine/threonine/tyrosine phosphorylation

Addition of a negatively charged phosphate group can lead to major changes in protein structure, leading to the well-characterised role of phosphorylation in controlling protein function. It is not clear what structural implications histone phosphorylation has, but histone phosphorylation has clear functions as a post-translational modification, and binding domains such as BRCT have been characterised.