4 Chromosomes: The Vectors of Heredity

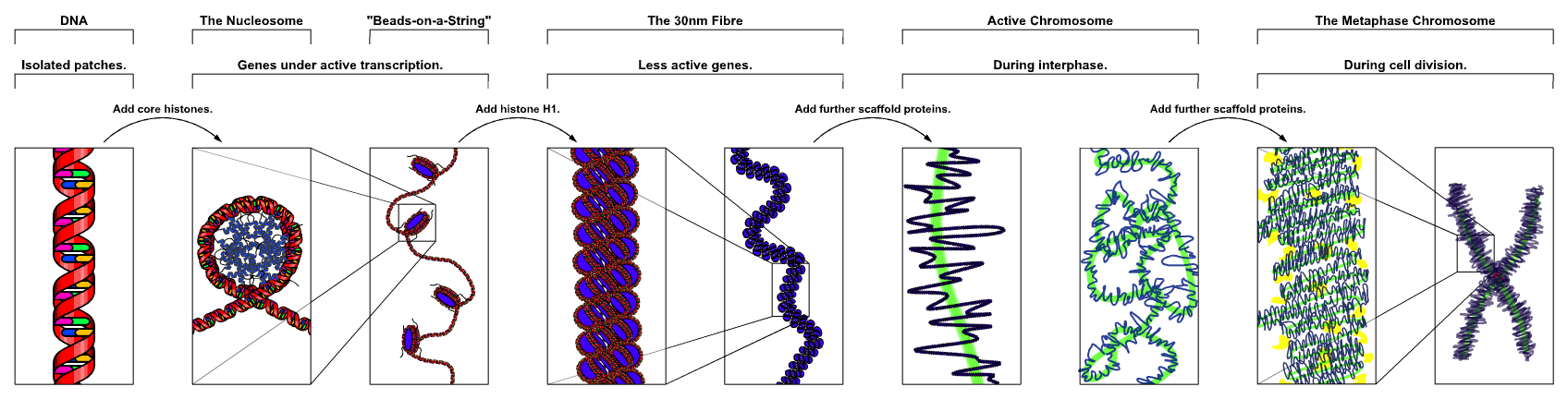

A chromosome is a deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) molecule with part or all of the genetic material (genome) of an organism. Most eukaryotic chromosomes include packaging proteins which, aided by chaperone proteins, bind to and condense the DNA molecule to prevent it from becoming an unmanageable tangle. This three-dimensional genome structure plays a significant role in transcriptional regulation

The word chromosome comes from the Greek χρῶμα (chroma, “colour”) and σῶμα (soma, “body”), describing their strong staining by particular dyes. The term was coined by the German scientist Heinrich Wilhelm Gottfired von Waldeyer-Hartz, referring to the term chromatin, which was itself introduced by Walther Flemming, who discovered cell division.

Chromosomes are normally visible under a light microscope only when the cell is undergoing cell division. Before this happens, every chromosome is copied once (S phase), and the copy is joined to the original by a centromere, resulting either in an X-shaped structure if the centromere is located in the middle of the chromosome or a two-arm structure if the centromere is located near one of the ends. The original chromosome and the copy are now called sister chromatids. During metaphase the X-shape structure is called a metaphase chromosome. In this highly condensed form chromosomes are easiest to distinguish and study. In animal cells, chromosomes reach their highest compaction level in anaphase during chromosome segregation.

Chromosomal recombination during meiosis and subsequent sexual reproduction play a significant role in genetic diversity. If these structures are manipulated incorrectly, through processes known as chromosomal instability and translocation, the cell may undergo mitotic catastrophe. Usually, this will make the cell initiate apoptosis leading to its own death, but sometimes mutations in the cell hamper this process and thus cause progression of cancer.

Some use the term chromosome in a wider sense, to refer to the individualized portions of chromatin in cells, either visible or not under light microscopy. Others use the concept in a narrower sense, to refer to the individualized portions of chromatin during cell division, visible under light microscopy due to high condensation.

The German scientists Schleiden, Virchow and Bütschli were among the first scientists who recognized the structures now familiar as chromosomes.

In a series of experiments beginning in the mid-1880s, Theodor Boveri gave the definitive demonstration that chromosomes are the vectors of heredity. Wilhelm Roux suggested that each chromosome carries a different genetic configuration, and Boveri was able to test and confirm this hypothesis. Aided by the rediscovery at the start of the 1900s of Gregor Mendel’s earlier work, Boveri was able to point out the connection between the rules of inheritance and the behaviour of the chromosomes.

In his famous textbook The Cell in Development and Heredity, Edmund Beecher Wilson linked together the independent work of Boveri and Sutton (both around 1902) by naming the chromosome theory of inheritance the Boveri–Sutton chromosome theory (the names are sometimes reversed). Ernst Mayr remarks that the theory was hotly contested by some famous geneticists: William Bateson, Wilhelm Johannsen, Richard Goldschmidt and T.H. Morgan. Eventually, complete proof came from chromosome maps in Morgan’s own lab.

The number of human chromosomes was published in 1923 by Theophilus Painter. By inspection through the microscope, he counted 24 pairs, which would mean 48 chromosomes. His error was copied by others and it was not until 1956 that the true number, 46, was determined by Indonesia-born cytogeneticist Joe Hin Tjio.

4.1 Prokaryotes

The prokaryotes – bacteria and archaea – typically have a single circular chromosome, but many variations exist. The chromosomes of most bacteria, which some authors prefer to call genophores, can range in size from only 130,000 base pairs in the endosymbiotic bacteria Candidatus Hodgkinia cicadicola and Candidatus Tremblaya princeps, to more than 14,000,000 base pairs in the soil-dwelling bacterium Sorangium cellulosum. Spirochaetes of the genus Borrelia are a notable exception to this arrangement, with bacteria such as Borrelia burgdorferi, the cause of Lyme disease, containing a single linear chromosome.

4.1.1 Structure in sequences

Prokaryotic chromosomes have less sequence-based structure than eukaryotes. Bacteria typically have a single origin of chromosomal replication (oriC; a particular DNA sequence from which replication starts), whereas some archaea contain multiple replication origins. The genes in prokaryotes are often organized in operons, and do not usually contain introns, unlike eukaryotes.

4.1.2 DNA packaging

Prokaryotes do not possess nuclei. Instead, their DNA is organized into a structure called the nucleoid. The nucleoid is a distinct structure and occupies a defined region of the bacterial cell. This structure is, however, dynamic and is maintained and remodeled by the actions of a range of histone-like proteins, which associate with the bacterial chromosome. In archaea, the DNA in chromosomes is even more organized, with the DNA packaged within structures similar to eukaryotic nucleosomes.

Certain bacteria also contain plasmids or other extrachromosomal DNA. These are circular DNA and play a role in horizontal gene transfer.

Bacterial chromosomes tend to be tethered to the plasma membrane of the bacteria. In molecular biology application, this allows for its isolation from plasmid DNA by centrifugation of lysed bacteria and pelleting of the membranes (and the attached DNA).

Prokaryotic chromosomes and plasmids are, like eukaryotic DNA, generally supercoiled. The DNA must first be released into its relaxed state for access for transcription, regulation, and replication.

4.2 Eukaryotes

Chromosomes in eukaryotes are composed of chromatin fiber. Chromatin fiber is made of nucleosomes (histone octamers with part of a DNA strand attached to and wrapped around it). Chromatin fibers are packaged by proteins into a condensed structure called chromatin. Chromatin contains the vast majority of DNA, but a small amount inherited maternally, can be found in the mitochondria. Chromatin is present in most cells, with a few exceptions, for example, red blood cells.

Chromatin allows the very long DNA molecules to fit into the cell nucleus. During cell division chromatin condenses further to form microscopically visible chromosomes. The structure of chromosomes varies through the cell cycle. During cellular division chromosomes are replicated, divided, and passed successfully to their daughter cells so as to ensure the genetic diversity and survival of their progeny. Chromosomes may exist as either duplicated or unduplicated. Unduplicated chromosomes are single double helixes, whereas duplicated chromosomes contain two identical copies (called chromatids or sister chromatids) joined by a centromere.

Eukaryotes possess multiple large linear chromosomes contained in the cell’s nucleus. Each chromosome has one centromere, with one or two arms projecting from the centromere, although, under most circumstances, these arms are not visible as such. In addition, most eukaryotes have a small circular mitochondrial genome, and some eukaryotes may have additional small circular or linear cytoplasmic chromosomes.

In the nuclear chromosomes of eukaryotes, the uncondensed DNA exists in a semi-ordered structure, where it is wrapped around histones (structural proteins), forming a composite material called chromatin.

4.2.1 Interphase chromatin

During interphase (the period of the cell cycle where the cell is not dividing), two types of chromatin can be distinguished:

- Euchromatin, which consists of DNA that is active, e.g., being expressed as protein.

- Heterochromatin, which consists of mostly inactive DNA. It seems to serve structural purposes during the chromosomal stages.

Heterochromatin can be further distinguished into two types

- Constitutive heterochromatin, which is never expressed. It is located around the centromere and usually contains repetitive sequences.

- Facultative heterochromatin, which is sometimes expressed.

4.2.2 Metaphase chromatin and division

In the early stages of mitosis or meiosis (cell division), the chromatin double helices become more and more condensed. They cease to function as accessible genetic material (transcription stops) and become a compact transportable form. This compact form makes the individual chromosomes visible, and they form the classic four arm structure, a pair of sister chromatids attached to each other at the centromere. The shorter arms are called p arms (from the French petit, small) and the longer arms are called q arms (q follows p in the Latin alphabet; q-g “grande”; alternatively it is sometimes said q is short for queue meaning tail in French). This is the only ntural context in which individual chromosomes are visible with an optical microscope.

Mitotic metaphase chromosomes are best described by a linearly organized longitudinally compressed array of consecutive chromatin loops.

During mitosis, microtubules grow from centrosomes located at opposite ends of the cell and also attach to the centromere at specialized structures called kinetochores, one of which is present on each sister chromatid. A special DNA base sequence in the region of the kinetochores provides, along with special proteins, longer-lasting attachment in this region. The microtubules then pull the chromatids apart toward the centrosomes, so that each daughter cell inherits one set of chromatids. Once the cells have divided, the chromatids are uncoiled and DNA can again be transcribed. In spite of their appearance, chromosomes are structurally highly condensed, which enables these giant DNA structures to be contained within a cell nucleus.

4.3 Human chromosomes

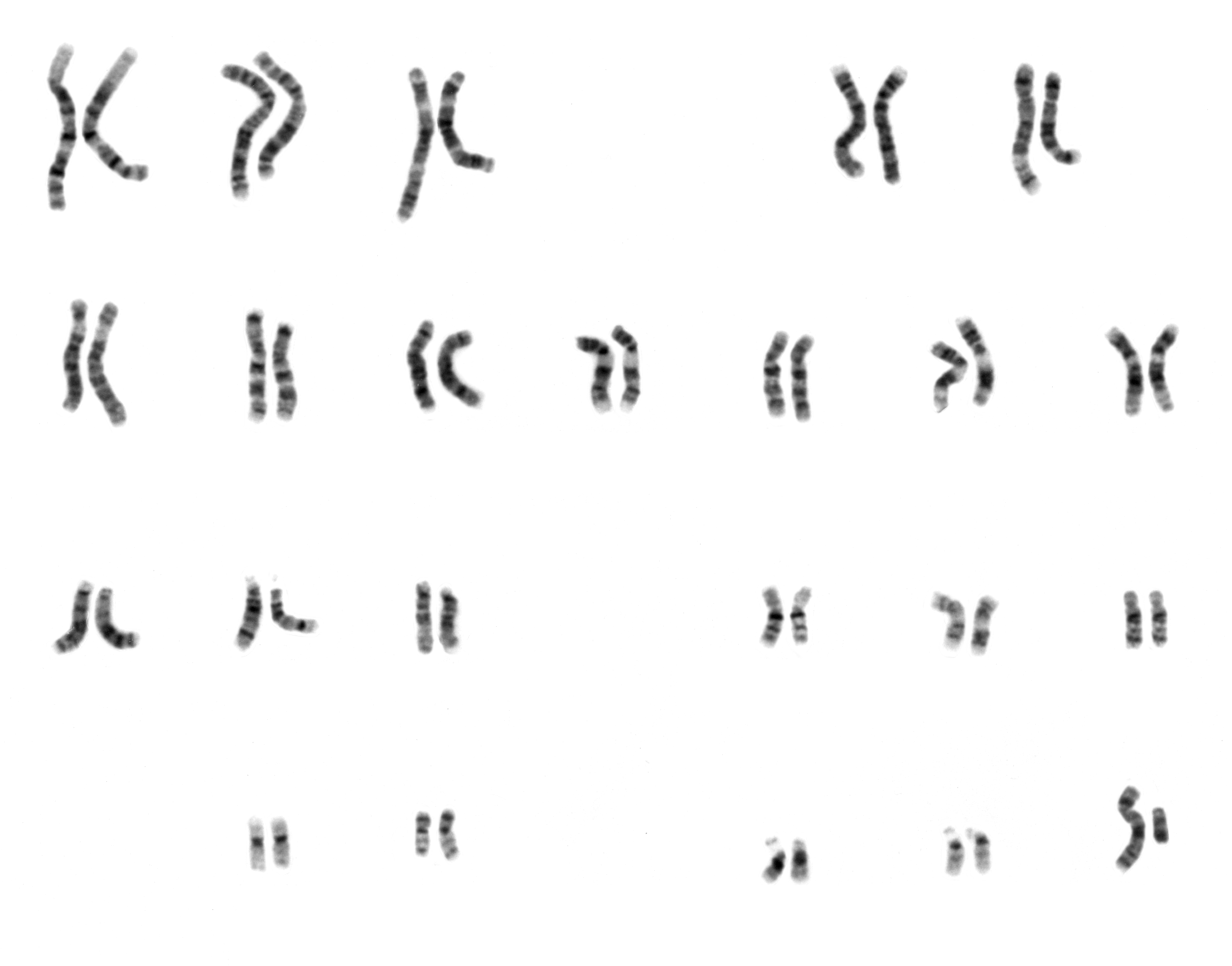

Chromosomes in humans can be divided into two types: autosomes (body chromosome(s)) and allosomes (sex chromosome(s)). Certain genetic traits are linked to a person’s sex and are passed on through the sex chromosomes. The autosomes contain the rest of the genetic hereditary information. All act in the same way during cell division. Human cells have 23 pairs of chromosomes (22 pairs of autosomes and one pair of sex chromosomes), giving a total of 46 per cell (Figure 1.11). In addition to these, human cells have many hundreds of copies of the mitochondrial genome. Sequencing of the human genome has provided a great deal of information about each of the chromosomes (Table 4.1).

| Chromosome | Total length | Coding genes |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 248,956,422 | 2,057 |

| 2 | 242,193,529 | 1,303 |

| 3 | 198,295,559 | 1,078 |

| 4 | 190,214,555 | 753 |

| 5 | 181,538,259 | 885 |

| 6 | 170,805,979 | 1,048 |

| 7 | 159,345,973 | 999 |

| 8 | 145,138,636 | 685 |

| 9 | 138,394,717 | 780 |

| 10 | 133,797,422 | 733 |

| 11 | 135,086,622 | 1,317 |

| 12 | 133,275,309 | 1,034 |

| 13 | 114,364,328 | 321 |

| 14 | 107,043,718 | 819 |

| 15 | 101,991,189 | 613 |

| 16 | 90,338,345 | 859 |

| 17 | 83,257,441 | 1,186 |

| 18 | 80,373,285 | 268 |

| 19 | 58,617,616 | 1,473 |

| 20 | 64,444,167 | 546 |

| 21 | 46,709,983 | 233 |

| 22 | 50,818,468 | 494 |

| X | 156,040,895 | 852 |

| Y | 57,227,415 | 66 |

| MT | 16,569 | 13 |

| Unplaced | 4,485,509 | |

| Genome | 3,099,734,149 | 20,415 |

4.4 Number of chromosomes in various organisms

The following tables (Tables 4.2 and 4.3) give the total number of chromosomes (including sex chromosomes) in a cell nucleus. For example, most eukaryotes are diploid, like humans who have 22 different types of autosomes, each present as homologous pairs (i.e. one chromosome of each type inherited from the mother and one from the father), and two sex chromosomes. This gives 46 chromosomes in total. Other organisms have more than two copies of their chromosome types, such as bread wheat, which is hexaploid and has six copies of seven different chromosome types – 42 chromosomes in total.

Normal members of a particular eukaryotic species all have the same number of nuclear chromosomes. Other eukaryotic chromosomes, i.e., mitochondrial and plasmid-like small chromosomes, are much more variable in number, and there may be thousands of copies per cell.

| Plant Species | # |

|---|---|

| Adder’s tongue fern (polyploid) | approx. 1,200 |

| Arabidopsis thaliana (diploid) | 10 |

| Einkorn wheat (diploid) | 14 |

| Rye (diploid) | 14 |

| Maize (diploid or palaeotetraploid) | 20 |

| Durum wheat (tetraploid) | 28 |

| Bread wheat (hexaploid) | 42 |

| Cultivated tobacco (tetraploid) | 48 |

| Species | # |

|---|---|

| Indian muntjac | 7 |

| Common fruit fly | 8 |

| Pill millipede (Arthrosphaera fumosa) | 30 |

| Earthworm (Octodrilus complanatus) | 36 |

| Tibetan fox | 36 |

| Domestic cat | 38 |

| Domestic pig | 38 |

| Laboratory mouse | 40 |

| Laboratory rat | 42 |

| Rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) | 44 |

| Syrian hamster | 44 |

| Guppy (Poecilia reticulata) | 46 |

| Human | 46 |

| Hares | 48 |

| Gorillas, chimpanzees | 48 |

| Domestic sheep | 54 |

| Garden snail | 54 |

| Silkworm | 56 |

| Elephants | 56 |

| Cow | 60 |

| Donkey | 62 |

| Guinea pig | 64 |

| Horse | 64 |

| Dog | 78 |

| Hedgehog | 90 |

| Goldfish | 100–104 |

| Kingfisher | 132 |

Asexually reproducing species have one set of chromosomes that are the same in all body cells. However, asexual species can be either haploid or diploid.

Sexually reproducing species have somatic cells (body cells), which are diploid [2n] having two sets of chromosomes (23 pairs in humans with one set of 23 chromosomes from each parent), one set from the mother and one from the father. Gametes, reproductive cells, are haploid [n]: They have one set of chromosomes. Gametes are produced by meiosis of a diploid germ line cell. During meiosis, the matching chromosomes of father and mother can exchange small parts of themselves (crossover), and thus create new chrmosomes that are not inherited solely from either parent. When a male and a female gamete merge (fertilization), a new diploid organism is formed.

Some animal and plant species are polyploid [Xn]: They have more than two sets of homologous chromosomes. Plants important in agriculture such as tobacco or wheat are often polyploid, compared to their ancestral species. Wheat has a haploid number of seven chromosomes, still seen in some cultivars as well as the wild progenitors. The more-common pasta and bread wheat types are polyploid, having 28 (tetraploid) and 42 (hexaploid) chromosomes, compared to the 14 (diploid) chromosomes in the wild wheat.

4.4.1 In prokaryotes

Prokaryote species generally have one copy of each major chromosome, but most cells can easily survive with multiple copies. For example, Buchnera, a symbiont of aphids has multiple copies of its chromosome, ranging from 10–400 copies per cell. However, in some large bacteria, such as Epulopiscium fishelsoni up to 100,000 copies of the chromosome can be present. Plasmids and plasmid-like small chromosomes are, as in eukaryotes, highly variable in copy number. The number of plasmids in the cell is almost entirely determined by the rate of division of the plasmid – fast division causes high copy number.

4.5 Karyotype

In general, the karyotype is the characteristic chromosome complement of a eukaryote species. The preparation and study of karyotypes is part of cytogenetics.

Although the replication and transcription of DNA is highly standardized in eukaryotes, the same cannot be said for their karyotypes, which are often highly variable. There may be variation between species in chromosome number and in detailed organization. In some cases, there is significant variation within species. Often there is:

- variation between the two sexes

- variation between the germ-line and soma (between gametes and the rest of the body)

- variation between members of a population, due to balanced genetic polymorphism

- geographical variation between races

- mosaics or otherwise abnormal individuals.

Also, variation in karyotype may occur during development from the fertilized egg.

The technique of determining the karyotype is usually called karyotyping. Cells can be locked part-way through division (in metaphase) in vitro (in a reaction vial) with colchicine. These cells are then stained, photographed, and arranged into a karyogram, with the set of chromosomes arranged, autosomes in order of length, and sex chromosomes (here X/Y) at the end.

Like many sexually reproducing species, humans have special gonosomes (sex chromosomes, in contrast to autosomes). These are XX in females and XY in males.

Investigation into the human karyotype (Figure 1.11) took many years to settle the most basic question: How many chromosomes does a normal diploid human cell contain? In 1912, Hans von Winiwarter reported 47 chromosomes in spermatogonia and 48 in oogonia, concluding an XX/XO sex determination mechanism. Painter in 1922 was not certain whether the diploid number of man is 46 or 48, at first favouring 46. He revised his opinion later from 46 to 48, and he correctly insisted on humans having an XX/XY system.

Human male karyotype. Human male karyotype.

Figure 1.11: Human male karyotype.

New techniques were needed to definitively solve the problem:

- Using cells in culture

- Arresting mitosis in metaphase by a solution of colchicine

- Pretreating cells in a hypotonic solution 0.075 M KCl, which swells them and spreads the chromosomes

- Squashing the preparation on the slide forcing the chromosomes into a single plane

- Cutting up a photomicrograph and arranging the result into an indisputable karyogram.

It took until 1954 before the human diploid number was confirmed as 46. Considering the techniques of Winiwarter and Painter, their results were quite remarkable. Chimpanzees, the closest living relatives to modern humans, have 48 chromosomes as do the other great apes: in humans two chromosomes fused to form chromosome 2.