5 The Cell Membrane

The cell membrane (also known as the plasma membrane (PM) or cytoplasmic membrane, and historically referred to as the plasmalemma) is a biological membrane that separates the interior of all cells from the outside environment (the extracellular space) which protects the cell from its environment. The cell membrane consists of a lipid bilayer, including sterols (e. g. cholesterol) that sit between phospholipids to maintain their fluidity at various temperatures. The membrane also contains membrane proteins, including integral proteins that go across the membrane serving as membrane transporters, and peripheral proteins that loosely attach to the outer (peripheral) side of the cell membrane, acting as enzymes shaping the cell. The cell mebrane controls the movement of substances in and out of cells and organelles. In this way, it is selectively permeable to ions and organic molecules. In addition, cell membranes are involved in a variety of cellular processes such as cell adhesion, ion conductivity and cell signalling and serve as the attachment surface for several extracellular structures, including the cell wall, the carbohydrate layer called the glycocalyx, and the intracellular network of protein fibers called the cytoskeleton. In the field of synthetic biology, cell membranes can be artificially reassembled.

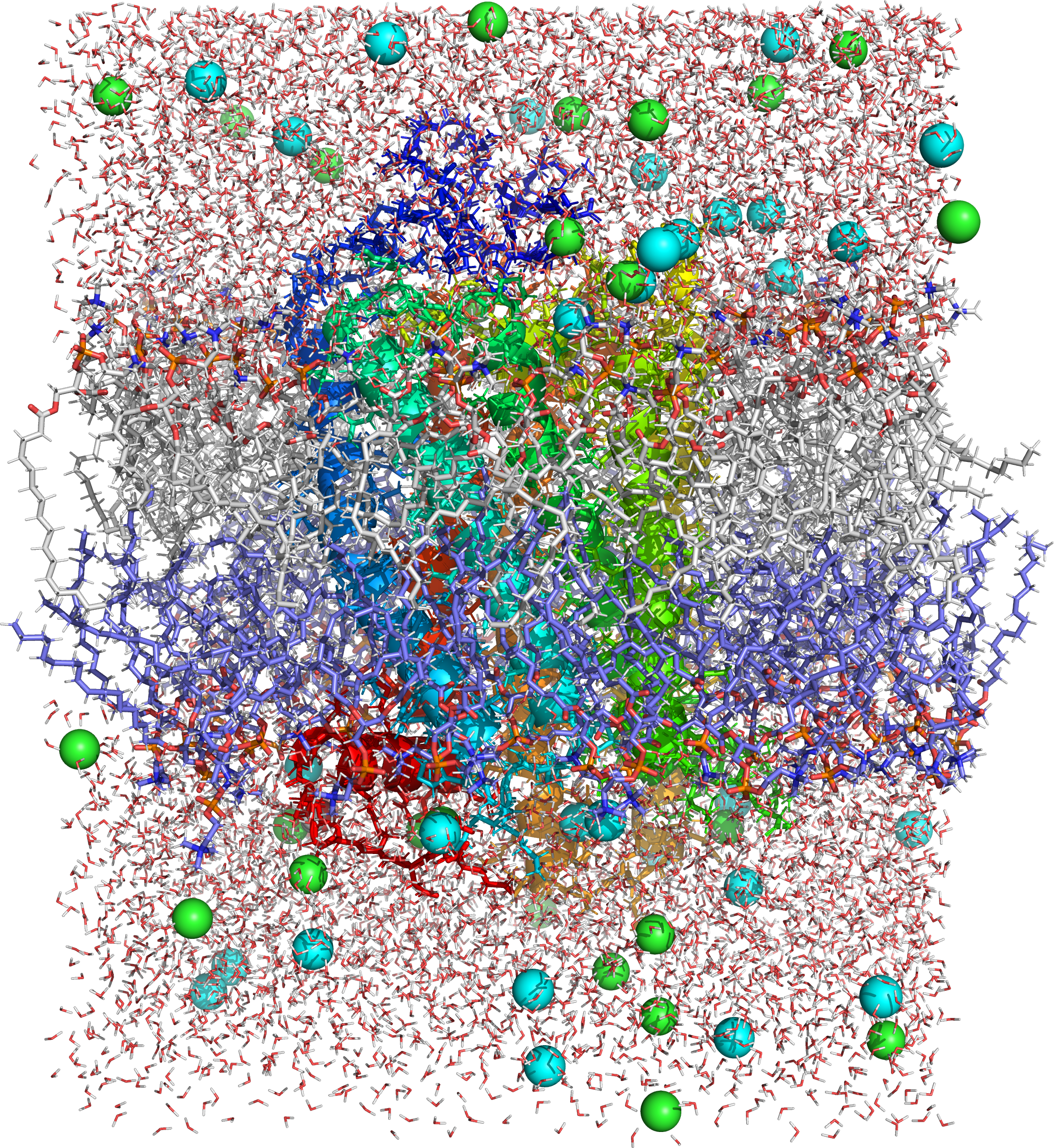

Figure 4.7: Picture of a molecular dynamics simulation of a cell membrane/protein complex consisting of bovine rhodopsin incorporated of a phosphatidylcholine (1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine, POPC) lipid bylayer. POPC and water molecules are depicted as sticks. The lipid layers facing the extracellular and cytoplasmic spaces are shown in white and blue, respectively. Both the extra- and intracellular interfaces are covered with layers of water. The secondary structure of rhodopsin is depicted in rainbow colored cartoon representation. Potassium and chloride ions are shown as spheres (colored in cyan and green, respectively). Image generated from PDB file obtained from the CHARMM-GUI Archive - Protein/Membrane Complex Library using the open source molecular visualization tool PyMol.

While Robert Hooke’s discovery of cells in 1665 led to the proposal of the Cell Theory, Hooke misled the cell membrane theory that all cells contained a hard cell wall since only plant cells could be observed at the time. Microscopists focused on the cell wall for well over 150 years until advances in microscopy were made. In the early 19th century, cells were recognized as being separate entities, unconnected, and bound by individual cell walls after it was found that plant cells could be separated. This theory extended to include animal cells to suggest a universal mechanism for cell protection and development. By the second half of the 19th century, microscopy was still not advanced enough to make a distinction between cell membranes and cell wals. However, some microscopists correctly identified at this time that while invisible, it could be inferred that cell membranes existed in animal cells due to intracellular movement of components internally but not externally and that membranes were not the equivalent of a cell wall to plant cell. It was also inferred that cell membranes were not vital components to all cells. Many refuted the existence of a cell membrane still towards the end of the 19th century. In 1890, an update to the Cell Theory stated that cell membranes existed, but were merely secondary structures. It was not until later studies with osmosis and permeability that cell membranes gained more recognition. In 1895, Ernest Overton proposed that cell membranes were made of lipids.

The lipid bilayer hypothesis, proposed in 1925 by Gorter and Grendel, created speculation to the description of the cell membrane bilayer structure based on crystallographic studies and soap bubble observations. In an attempt to accept or reject the hypothesis, researchers measured membrane thickness. In 1925 it was determined by Fricke that the thickness of erythrocyte and yeast cell membranes ranged between 3.3 and 4 nm, a thickness compatible with a lipid monolayer. The choice of the dielectric constant used in these studies was called into question but future tests could not disprove the results of the initial experiment. Independently, the leptoscope was invented in order to measure very thin membranes by comparing the intensity of light reflected from a sample to the intensity of a membrane standard of known thickness. The instrument could resolve thicknesses that depended on pH measurements and the presence of membrane proteins that ranged from 8.6 to 23.2 nm, with the lower measurements supporting the lipid bilayer hypothesis. Later in the 1930s, the membrane structure model developed in general agreement to be the paucimolecular model of Davson and Danielli (1935). This model was based on studies of surface tension between oils and echinoderm eggs. Since the surface tension values appeared to be much lower than would be expected for an oil–water interface, it was assumed that some substance was responsible for lowering the interfacial tensions in the surface of cells. It was suggested that a lipid bilayer was in between two thin protein layers. The paucimolecular model immediately became popular and it dominated cell membrane studies for the following 30 years, until it became rivaled by the fluid mosaic model of Singer and Nicolson (1972).

Despite the numerous models of the cell membrane proposed prior to the fluid mosaic model, it remains the primary archetype for the cell membrane long after its inception in the 1970s. Although the fluid mosaic model has been modernized to detail contemporary discoveries, the basics have remained constant: the membrane is a lipid bilayer composed of hydrophilic exterior heads and a hydrophobic interior where proteins can interact with hydrophilic heads through polar interactions, but proteins that span the bilayer fully or partially have hydrophobic amino acids that interact with the non-polar lipid interior. The fluid mosaic model not only provided an accurate representation of membrane mechanics, it enhanced the study of hydrophobic forces, which would later develop into an essential descriptive limitation to describe biological macromolecules.

For many centuries, the scientists cited disagreed with the significance of the structure they were seeing as the cell membrane. For almost two centuries, the membranes were seen but mostly disregarded this as an important structure with cellular function. It was not until the 20th century that the significance of the cell membrane as it was acknowledged. Finally, two scientists Gorter and Grendel (1925) made the discovery that the membrane is “lipid-based”. From this, they furthered the idea that this structure would have to be in a formation that mimicked layers. Once studied further, it was found by comparing the sum of the cell surfaces and the surfaces of the lipids, a 2:1 ratio was estimated; thus, providing the first basis of the bilayer structure known today. This discovery initiated many new studies that arose globally within various fields of scientific studies, confirming that the structure and functions of the cell membrane are widely accepted.

The structure has been variously referred to by different writers as the ectoplast (de Vries, 1885), Plasmahaut (plasma skin, Pfeffer, 1877, 1891), Hautschicht (skin layer, Pfeffer, 1886; used with a different meaning by Hofmeister, 1867), plasmatic membrane (Pfeffer, 1900), plasma membrane, cytoplasmic membrane, cell envelope and cell membrane. Some authors who did not believe that there was a functional permeable boundary at the surface of the cell preferred to use the term plasmalemma (coined by Mast, 1924) for the external region of the cell.

Cell membranes contain a variety of biological molecules, notably lipids and proteins. Composition is not set, but constantly changing for fluidity and changes in the environment, even fluctuating during different stages of cell development. Specifically, the amount of cholesterol in human primary neuron cell membrane changes, and this change in composition affects fluidity throughout development stages.

Material is incorporated into the membrane, or deleted from it, by a variety of mechanisms:

Fusion of intracellular vesicles with the membrane (exocytosis) not only excretes the contents of the vesicle but also incorporates the vesicle membrane’s components into the cell membrane. The membrane may form blebs around extracellular material that pinch off to become vesicles (endocytosis). If a membrane is continuous with a tubular structure made of membrane material, then material from the tube can be drawn into the membrane continuously. Although the concentration of membrane components in the aqueous phase is low (stable membrane components have low solubility in water), there is an exchange of molecules between the lipid and aqueous phases.

The cell membrane consists of three classes of amphipathic lipids: phospholipids, glycolipids, and sterols. The amount of each depends upon the type of cell, but in the majority of cases phospholipids are the most abundant, often contributing for over 50% of all lipids in plasma membranes. Glycolipids only account for a minute amount of about 2% and sterols make up the rest. In RBC studies, 30% of the plasma membrane is lipid. However, for the majority of eukaryotic cells, the composition of plasma membranes is about half lipids and half proteins by weight.

The fatty chains in phospholipids and glycolipids usually contain an even number of carbon atoms, typically between 16 and 20. The 16- and 18-carbon fatty acids are the most common. Fatty acids may be saturated or unsaturated, with the configuration of the double bonds nearly always “cis”. The length and the degree of unsaturation of fatty acid chains have a profound effect on membrane fluidity as unsaturated lipids create a kink, preventing the fatty acids from packing together as tightly, thus decreasing the melting temperature (increasing the fluidity) of the membrane. The ability of some organisms to regulate the fluidity of their cell membranes by altering lipid composition is called homeoviscous adaptation.

The entire membrane is held together via non-covalent interaction of hydrophobic tails, however the structure is quite fluid and not fixed rigidly in place. Under physiological conditions phospholipid molecules in the cell membrane are in the liquid crystalline state. It means the lipid molecules are free to diffuse and exhibit rapid lateral diffusion along the layer in which they are present. However, the exchange of phospholipid molecules between intracellular and extracellular leaflets of the bilayer is a very slow process. Lipid rafts and caveolae are examples of cholesterol-enriched microdomains in the cell membrane. Also, a fraction of the lipid in direct contact with integral membrane proteins, which is tightly bound to the protein surface is called annular lipid shell; it behaves as a part of protein complex.

In animal cells cholesterol is normally found dispersed in varying degrees throughout cell membranes, in the irregular spaces between the hydrophobic tails of the membrane lipids, where it confers a stiffening and strengthening effect on the membrane. Additionally, the amount of cholesterol in biological membranes varies between organisms, cell types, and even in individual cells. Cholesterol, a major component of animal plasma membranes, regulates the fluidity of the overall membrane, meaning that cholesterol controls the amount of movement of the various cell membrane components based on its concentrations. In high temperatures, cholesterol inhibits the movement of phospholipid fatty acid chains, causing a reduced permeability to small molecules and reduced membrane fluidity. The opposite is true for the role of cholesterol in cooler temperatures. Cholesterol production, and thus concentration, is up-regulated (increased) in response to cold temperature. At cold temperatures, cholesterol interferes with fatty acid chain interactions. Acting as antifreeze, cholesterol maintains the fluidity of the membrane. Cholesterol is more abundant in cold-weather animals than warm-weather animals. In plants, which lack cholesterol, related compounds called sterols perform the same function as cholesterol.

Plasma membranes also contain carbohydrates, predominantly glycoproteins, but with some glycolipids (cerebrosides and gangliosides). Carbohydrates are important in the role of cell-cell recognition in eukaryotes; they are located on the surface of the cell where they recognize host cells and share information, viruses that bind to cells using these receptors cause an infection For the most part, no glycosylation occurs on membranes within the cell; rather generally glycosylation occurs on the extracellular surface of the plasma membrane. The glycocalyx is an important feature in all cells, especially epithelia with microvilli. Recent data suggest the glycocalyx participates in cell adhesion, lymphocyte homing, and many others. The penultimate sugar is galactose and the terminal sugar is sialic acid, as the sugar backbone is modified in the Golgi apparatus. Sialic acid carries a negative charge, providing an external barrier to charged particles.

The cell membrane has large content of proteins, typically around 50% of membrane volume These proteins are important for the cell because they are responsible for various biological activities. Approximately a third of the genes in yeast code specifically for them, and this number is even higher in multicellular organisms. Membrane proteins consist of three main types: integral proteins, peripheral proteins, and lipid-anchored proteins.

As shown in the adjacent table, integral proteins are amphipathic transmembrane proteins. Examples of integral proteins include ion channels, proton pumps, and g-protein coupled receptors. Ion channels allow inorganic ions such as sodium, potassium, calcium, or chlorine to diffuse down their electrochemical gradient across the lipid bilayer through hydrophilic pores across the membrane. The electrical behavior of cells (i.e. nerve cells) are controlled by ion channels. Proton pumps are protein pumps that are embedded in the lipid bilayer that allow protons to travel through the membrane by transferring from one amino acid side chain to another. Processes such as electron transport and generating ATP use proton pumps. A G-protein coupled receptor is a single polypeptide chain that crosses the lipid bilayer seven times responding to signal molecules (i.e. hormones and neurotransmitters). G-protein coupled receptors are used in processes such as cell to cell signaling, the regulation of the production of cAMP, and the regulation of ion channels.

The cell membrane, being exposed to the outside environment, is an important site of cell–cell communication. As such, a large variety of protein receptors and identification proteins, such as antigens, are present on the surface of the membrane. Functions of membrane proteins can also include cell–cell contact, surface recognition, cytoskeleton contact, signaling, enzymatic activity, or transporting substances across the membrane.

Most membrane proteins must be inserted in some way into the membrane. For this to occur, an N-terminus “signal sequence” of amino acids directs proteins to the endoplasmic reticulum, which inserts the proteins into a lipid bilayer. Once inserted, the proteins are then transported to their final destination in vesicles, where the vesicle fuses with the target membrane.

| Type | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Integral proteins or transmembrane proteins | Span the membrane and have a hydrophilic cytosolic domain, which interacts with internal molecules, a hydrophobic membrane-spanning domain that anchors it within the cell membrane, and a hydrophilic extracellular domain that interacts with external molecules. The hydrophobic domain consists of one, multiple, or a combination of α-helices and β sheet protein motifs. | Ion channels, proton pumps, G protein-coupled receptor |

| Lipid anchored proteins | Covalently bound to single or multiple lipid molecules; hydrophobically insert into the cell membrane and anchor the protein. The protein itself is not in contact with the membrane. | G proteins |

| Peripheral proteins | Attached to integral membrane proteins, or associated with peripheral regions of the lipid bilayer. These proteins tend to have only temporary interactions with biological membranes, and once reacted, the molecule dissociates to carry on its work in the cytoplasm. | Some enzymes, some hormones |

5.1 Structure And Function of The Cell Membrane

The cell membrane surrounds the cytoplasm of living cells, physically separating the intracellular components from the extracellular environment. The cell membrane also plays a role in anchoring the cytoskeleton to provide shape to the cell, and in attaching to the extracellular matrix and other cells to hold them together to form tissues. Fungi, bacteria, most archaea, and plants also have a cell wall, which provides a mechanical support to the cell and precludes the passage of larger molecules.

The cell membrane is selectively permeable and able to regulate what enters and exits the cell, thus facilitating the transport of materials needed for survival. The movement of substances across the membrane can be either “passive”, occurring without the input of cellular energy, or “active”, requiring the cell to expend energy in transporting it. The membrane also maintains the cell potential. The cell membrane thus works as a selective filter that allows only certain things to come inside or go outside the cell. The cell employs a number of transport mechanisms that involve biological membranes:

Passive osmosis and diffusion: Some substances (small molecules, ions) such as carbon dioxide (CO2) and oxygen (O2), can move across the plasma membrane by diffusion, which is a passive transport process. Because the membrane acts as a barrier for certain molecules and ions, they can occur in different concentrations on the two sides of the membrane. Diffusion occurs when small molecules and ions move freely from high concentration to low concentration in order to equilibrate the membrane. It is considered a passive transport process because it does not require energy and is propelled by the concentration gradient created by each side of the membrane. Such a concentration gradient across a semipermeable membrane sets up an osmotic flow for the water. Osmosis, in biological systems involves a solvent, moving through a semipermeable membrane similarly to passive diffusion as the solvent still moves with the concentration gradient and requires no energy. While water is the most common solvent in cell, it can also be other liquids as well as supercritical liquids and gases.

Transmembrane protein channels and transporters: Transmembrane proteins extend through the lipid bilayer of the membranes; they function on both sides of the membrane to transport molecules across it. Nutrients, such as sugars or amino acids, must enter the cell, and certain products of metabolism must leave the cell. Such molecules can diffuse passively through protein channels such as aquaporins in facilitated diffusion or are pumped across the membrane by transmembrane transporters. Protein channel proteins, also called permeases, are usually quite specific, and they only recognize and transport a limited variety of chemical substances, often limited to a single substance. Another example of a transmembrane protein is a cell-surface receptor, which allow cell signaling molecules to communicate between cells.

Endocytosis: Endocytosis is the process in which cells absorb molecules by engulfing them. The plasma membrane creates a small deformation inward, called an invagination, in which the substance to be transported is captured.This invagination is caused by proteins on the outside on the cell membrane, acting as receptors and clustering into depressions that eventually promote accumulation of more proteins and lipids on the cytosolic side of the membrane. The deformation then pinches off from the membrane on the inside of the cell, creating a vesicle containing the captured substance. Endocytosis is a pathway for internalizing solid particles (“cell eating” or phagocytosis), small molecules and ions (“cell drinking” or pinocytosis), and macromolecules. Endocytosis requires energy and is thus a form of active transport.

Exocytosis: Just as material can be brought into the cell by invagination and formation of a vesicle, the membrane of a vesicle can be fused with the plasma membrane, extruding its contents to the surrounding medium. This is the process of exocytosis. Exocytosis occurs in various cells to remove undigested residues of substances brought in by endocytosis, to secrete substances such as hormones and enzymes, and to transport a substance completely across a cellular barrier. In the process of exocytosis, the undigested waste-containing food vacuole or the secretory vesicle budded from Golgi apparatus, is first moved by cytoskeleton from the interior of the cell to the surface. The vesicle membrane comes in contact with the plasma membrane. The lipid molecules of the two bilayers rearrange themselves and the two membranes are, thus, fused. A passage is formed in the fused membrane and the vesicles discharges its contents outside the cell.

5.1.1 The Fluid Mosaic Model of The Cell Membrane

According to the fluid mosaic model of S. J. Singer and G. L. Nicolson (1972), which replaced the earlier model of Davson and Danielli, biological membranes can be considered as a two-dimensional liquid in which lipid and protein molecules diffuse more or less easily. Although the lipid bilayers that form the basis of the membranes do indeed form two-dimensional liquids by themselves, the plasma membrane also contains a large quantity of proteins, which provide more structure. Examples of such structures are protein-protein complexes, pickets and fences formed by the actin-based cytoskeleton, and potentially lipid rafts.

5.1.2 Lipid bilayer

Lipid bilayers form through the process of self-assembly. The cell membrane consists primarily of a thin layer of amphipathic phospholipids that spontaneously arrange so that the hydrophobic “tail” regions are isolated from the surrounding water while the hydrophilic “head” regions interact with the intracellular (cytosolic) and extracellular faces of the resulting bilayer. This forms a continuous, spherical lipid bilayer. Hydrophobic interactions (also known as the hydrophobic effect) are the major driving forces in the formation of lipid bilayers. An increase in interactions between hydrophobic molecules (causing clustering of hydrophobic regions) allows water molecules to bond more freely with each other, increasing the entropy of the system. This complex interaction can include noncovalent interactions such as van der Waals, electrostatic and hydrogen bonds.

Lipid bilayers are generally impermeable to ions and polar molecules. The arrangement of hydrophilic heads and hydrophobic tails of the lipid bilayer prevent polar solutes (ex. amino acids, nucleic acids, carbohydrates, proteins, and ions) from diffusing across the membrane, but generally allows for the passive diffusion of hydrophobic molecules. This affords the cell the ability to control the movement of these substances via transmembrane protein complexes such as pores, channels and gates. Flippases and scramblases concentrate phosphatidyl serine, which carries a negative charge, on the inner membrane. Along with NANA, this creates an extra barrier to charged moieties moving through the membrane.

Membranes serve diverse functions in eukaryotic and prokaryotic cells. One important role is to regulate the movement of materials into and out of cells. The phospholipid bilayer structure (fluid mosaic model) with specific membrane proteins accounts for the selective permeability of the membrane and passive and active transport mechanisms. In addition, membranes in prokaryotes and in the mitochondria and chloroplasts of eukaryotes facilitate the synthesis of ATP through chemiosmosis.

5.1.3 Membrane Polarity

The apical membrane of a polarized cell is the surface of the plasma membrane that faces inward to the lumen. This is particularly evident in epithelial and endothelial cells, but also describes other polarized cells, such as neurons. The basolateral membrane of a polarized cell is the surface of the plasma membrane that forms its basal and lateral surfaces. It faces outwards, towards the interstitium, and away from the lumen. Basolateral membrane is a compound phrase referring to the terms “basal (base) membrane” and “lateral (side) membrane”, which, especially in epithelial cells, are identical in composition and activity. Proteins (such as ion channels and pumps) are free to move from the basal to the lateral surface of the cell or vice versa in accordance with the fluid mosaic model. Tight junctions join epithelial cells near their apical surface to prevent the migration of proteins from the basolateral membrane to the apical membrane. The basal and lateral surfaces thus remain roughly equivalent[clarification needed] to one another, yet distinct from the apical surface.

Cell membrane can form different types of “supramembrane” structures such as caveola, postsynaptic density, podosome, invadopodium, focal adhesion, and different types of cell junctions. These structures are usually responsible for cell adhesion, communication, endocytosis and exocytosis. They can be visualized by electron microscopy or fluorescence microscopy. They are composed of specific proteins, such as integrins and cadherins.

5.1.4 The Cytoskeleton

The cytoskeleton is found underlying the cell membrane in the cytoplasm and provides a scaffolding for membrane proteins to anchor to, as well as forming organelles that extend from the cell. Indeed, cytoskeletal elements interact extensively and intimately with the cell membrane. Anchoring proteins restricts them to a particular cell surface — for example, the apical surface of epithelial cells that line the vertebrate gut — and limits how far they may diffuse within the bilayer. The cytoskeleton is able to form appendage-like organelles, such as cilia, which are microtubule-based extensions covered by the cell membrane, and filopodia, which are actin-based extensions. These extensions are ensheathed in membrane and project from the surface of the cell in order to sense the external environment and/or make contact with the substrate or other cells. The apical surfaces of epithelial cells are dense with actin-based finger-like projections known as microvilli, which increase cell surface area and thereby increase the absorption rate of nutrients. Localized decoupling of the cytoskeleton and cell membrane results in formation of a bleb.

5.1.5 Intracellular Membranes In Eukaryotic Cells

The content of the cell, inside the cell membrane, is composed of numerous membrane-bound organelles, which contribute to the overall function of the cell. The origin, structure, and function of each organelle leads to a large variation in the cell composition due to the individual uniqueness associated with each organelle.

- Mitochondria and chloroplasts are considered to have evolved from bacteria, known as the endosymbiotic theory. This theory arose from the idea that Paracoccus and Rhodopseaudomonas, types of bacteria, share similar functions to mitochondria and blue-green algae, or cyanobacteria, share similar functions to chloroplasts. The endosymbiotic theory proposes that through the course of evolution, a eukaryotic cell engulfed these 2 types of bacteria, leading to the formation of mitochondria and chloroplasts inside eukaryotic cells. This engulfment lead to the 2 membranes systems of these organelles in which the outer membrane originated from the host’s plasma membrane and the inner membrane was the endosymbiont’s plasma membrane. Considering that mitochondria and chloroplasts both contain their own DNA is further support that both of these organelles evolved from engulfed bacteria that thrived inside a eukaryotic cell.

- In eukaryotic cells, the nuclear membrane separates the contents of the nucleus from the cytoplasm of the cell. The nuclear membrane is formed by an inner and outer membrane, providing the strict regulation of materials in to and out of the nucleus. Materials move between the cytosol and the nucleus through nuclear pores in the nuclear membrane. If a cell’s nucleus is more active in transcription, its membrane will have more pores. The protein composition of the nucleus can vary greatly from the cytosol as many proteins are unable to cross through pores via diffusion. Within the nuclear membrane, the inner and outer membranes vary in protein composition, and only the outer membrane is continuous with the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane. Like the ER, the outer membrane also possesses ribosomes responsible for producing and transporting proteins into the space between the two membranes. The nuclear membrane disassembles during the early stages of mitosis and reassembles in later stages of mitosis.

- The ER, which is part of the endomembrane system, which makes up a very large portion of the cell’s total membrane content. The ER is an enclosed network of tubules and sacs, and its main functions include protein synthesis, and lipid metabolism. There are 2 types of ER, smooth and rough. The rough ER has ribosomes attached to it used for protein synthesis, while the smooth ER is used more for the processing of toxins and calcium regulation in the cell.

- The Golgi apparatus has two interconnected round Golgi cisternae. Compartments of the apparatus forms multiple tubular-reticular networks responsible for organization, stack connection and cargo transport that display a continuous grape-like stringed vesicles ranging from 50-60 nm. The apparatus consists of three main compartments, a flat disc-shaped cisterna with tubular-reticular networks and vesicles.

5.2 Membrane Permeability

The permeability of a membrane is the rate of passive diffusion of molecules through the membrane. These molecules are known as permeant molecules. Permeability depends mainly on the electric charge and polarity of the molecule and to a lesser extent the molar mass of the molecule. Due to the cell membrane’s hydrophobic nature, small electrically neutral molecules pass through the membrane more easily than charged, large ones. The inability of charged molecules to pass through the cell membrane results in pH partition of substances throughout the fluid compartments of the body. Because of these properties, the cell membrane is referred to as as selectively (or semi-) permeable membrane.

5.2.1 Diffusion

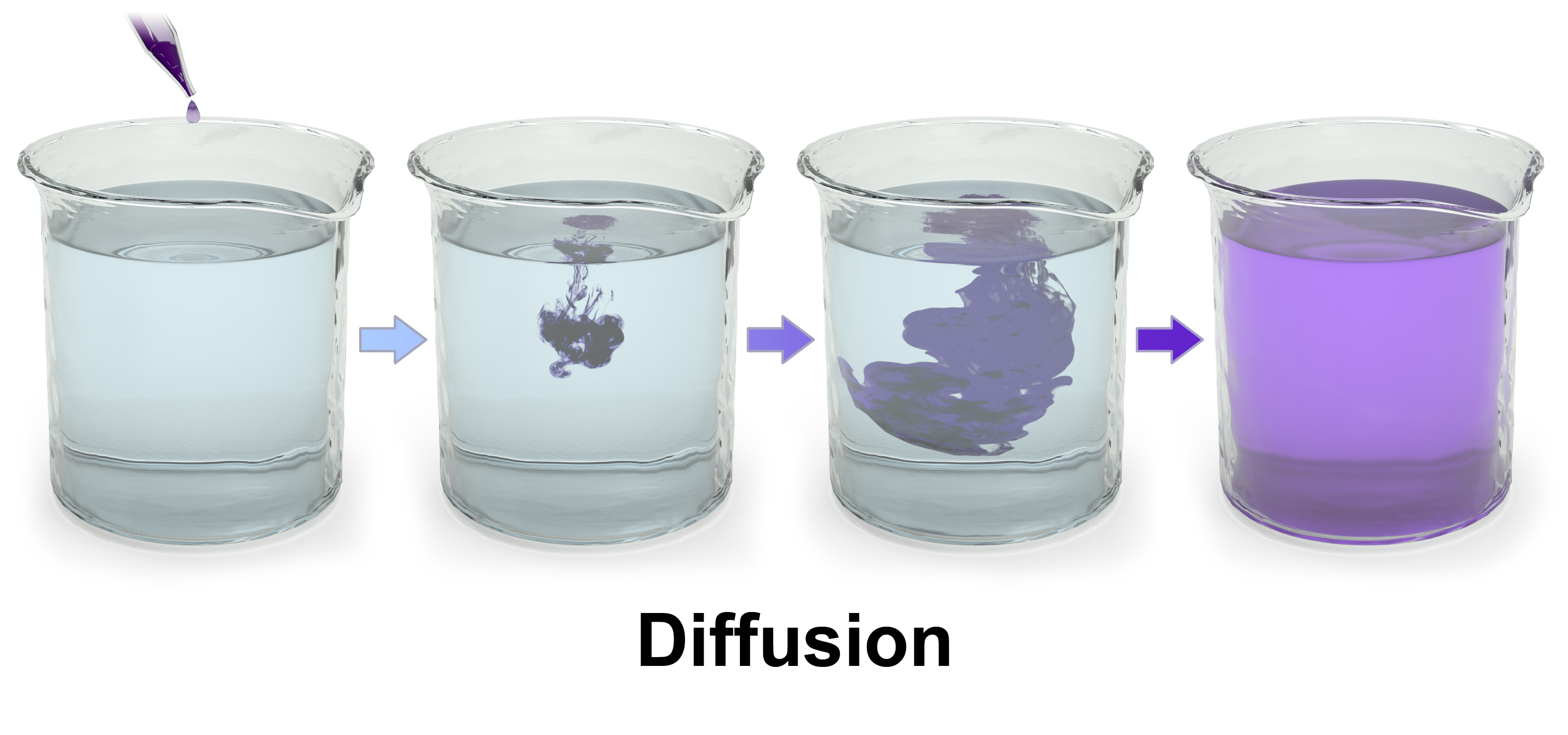

Diffusion is the net movement of material from an area of high concentration to an area with lower concentration. The difference of concentration between the two areas is often termed as the concentration gradient, and diffusion will continue until this gradient has been eliminated. Since diffusion moves materials from an area of higher concentration to an area of lower concentration, it is described as moving solutes “down the concentration gradient” (compared with active transport, which often moves material from area of low concentration to area of higher concentration, and therefore referred to as moving the material “against the concentration gradient”). However, in many cases (e.g. passive drug transport) the driving force of passive transport can not be simplified to the concentration gradient. If there are different solutions at the two sides of the membrane with different equilibrium solubility of the drug, the difference in degree of saturation is the driving force of passive membrane transport. It is also true for supersaturated solutions which are more and more important owing to the spreading of the application of amorphous solid dispersions for drug bioavailability enhancement.

Figure 5.1: Diffusion of a purple dye in water.

Simple diffusion and osmosis are in some ways similar. Simple diffusion is the passive movement of solute from a high concentration to a lower concentration until the concentration of the solute is uniform throughout and reaches equilibrium. Osmosis is much like simple diffusion but it specifically describes the movement of water (not the solute) across a selectively permeable membrane until there is an equal concentration of water and solute on both sides of the membrane. Simple diffusion and osmosis are both forms of passive transport and require none of the cell’s ATP energy.

5.2.2 Facilitated Diffusion

Facilitated diffusion, also called carrier-mediated osmosis, is the movement of molecules across the cell membrane via special transport proteins that are embedded in the plasma membrane by actively taking up or excluding ions. Active transport of protons by H+ ATPases alters membrane potential allowing for facilitated passive transport of particular ions such as potassium down their charge gradient through high affinity transporters and channels.

5.2.3 Osmosis

Osmosis is the movement of water molecules across a selectively permeable membrane. The net movement of water molecules through a partially permeable membrane from a solution of high water potential to an area of low water potential. A cell with a less negative water potential will draw in water but this depends on other factors as well such as solute potential (pressure in the cell e.g. solute molecules) and pressure potential (external pressure e.g. cell wall). There are three types of Osmosis solutions: the isotonic solution, hypotonic solution, and hypertonic solution. Isotonic solution is when the extracellular solute concentration is balanced with the concentration inside the cell. In the Isotonic solution, the water molecules still moves between the solutions, but the rates are the same from both directions, thus the water movement is balanced between the inside of the cell as well as the outside of the cell. A hypotonic solution is when the solute concentration outside the cell is lower than the concentration inside the cell. In hypotonic solutions, the water moves into the cell, down its concentration gradient (from higher to lower water concentrations). That can cause the cell to swell. Cells that don’t have a cell wall, such as animal cells, could burst in this solution. A hypertonic solution is when the solute concentration is higher (think of hyper - as high) than the concentration inside the cell. In hypertonic solution, the water will move out, causing the cell to shrink.

Figure 5.2: An example of osmosis: a semi-permeable (selectively permebable) membrane separates two compartments containing a higher concentration of a dissolved salt on the left side compared to the right side (i.e. the left side is hypertonic compared to the (hypotonic) right side). A net flow of water will occur from the right to the left side until the concentration of salt on both sides of the membrane is equal (i.e. both sides are isotonic).)

5.2.4 Active Transport

Unlike passive transport, which uses the kinetic energy and natural entropy of molecules moving down a gradient, active transport uses cellular energy to move them against a gradient, polar repulsion, or other resistance. Active transport is usually associated with accumulating high concentrations of molecules that the cell needs, such as ions, glucose and amino acids. Examples of active transport include the uptake of glucose in the intestines in humans and the uptake of mineral ions into root hair cells of plants.

There are two types of active transport: primary active transport that uses adenosine triphosphate (ATP), and secondary active transport that uses an electrochemical gradient. An example of active transport in human physiology is the uptake of glucose in the intestines.

5.2.5 Bulk transport

Endocytosis and exocytosis are both forms of bulk transport that move materials into and out of cells, respectively, via vesicles. In the case of endocytosis, the cellular membrane folds around the desired materials outside the cell. The ingested particle becomes trapped within a pouch, known as a vesicle, inside the cytoplasm. Often enzymes from lysosomes are then used to digest the molecules absorbed by this process. Substances that enter the cell via signal mediated electrolysis include proteins, hormones and growth and stabilization factors. Viruses enter cells through a form of endocytosis that involves their outer membrane fusing with the membrane of the cell. This forces the viral DNA into the host cell.

Biologists distinguish two main types of endocytosis: pinocytosis and phagocytosis.

- In pinocytosis, cells engulf liquid particles (in humans this process occurs in the small intestine, where cells engulf fat droplets).

- In phagocytosis, cells engulf solid particles. Exocytosis involves the removal of substances through the fusion of the outer cell membrane and a vesicle membrane An example of exocytosis would be the transmission of neurotransmitters across a synapse between brain cells.

5.3 The Extracellular Matrix

In biology, the extracellular matrix (ECM) is a three-dimensional network of extracellular macromolecules, such as collagen, enzymes, and glycoproteins, that provide structural and biochemical support to surrounding cells. Because multicellularity evolved independently in different multicellular lineages, the composition of ECM varies between multicellular structures; however, cell adhesion, cell-to-cell communication and differentiation are common functions of the ECM.

The animal extracellular matrix includes the interstitial matrix and the basement membrane. Interstitial matrix is present between various animal cells (i.e., in the intercellular spaces). Gels of polysaccharides and fibrous proteins fill the interstitial space and act as a compression buffer against the stress placed on the ECM. Basement membranes are sheet-like depositions of ECM on which various epithelial cells rest. Each type of connective tissue in animals has a type of ECM: collagen fibers and bone mineral comprise the ECM of bone tissue; reticular fibers and ground substance comprise the ECM of loose connective tissue; and blood plasma is the ECM of blood.

The plant ECM includes cell wall components, like cellulose, in addition to more complex signaling molecules. Some single-celled organisms adopt multicellular biofilms in which the cells are embedded in an ECM composed primarily of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS).

Due to its diverse nature and composition, the ECM can serve many functions, such as providing support, segregating tissues from one another, and regulating intercellular communication. The extracellular matrix regulates a cell’s dynamic behavior. In addition, it sequesters a wide range of cellular growth factors and acts as a local store for them. Changes in physiological conditions can trigger protease activities that cause local release of such stores. This allows the rapid and local growth factor-mediated activation of cellular functions without de novo synthesis.

Formation of the extracellular matrix is essential for processes like growth, wound healing, and fibrosis. An understanding of ECM structure and composition also helps in comprehending the complex dynamics of tumor invasion and metastasis in cancer biology as metastasis often involves the destruction of extracellular matrix by enzymes such as serine proteases, threonine proteases, and matrix metalloproteinases.

The stiffness and elasticity of the ECM has important implications in cell migration, gene expression, and differentiation. Cells actively sense ECM rigidity and migrate preferentially towards stiffer surfaces in a phenomenon called durotaxis. They also detect elasticity and adjust their gene expression accordingly which has increasingly become a subject of research because of its impact on differentiation and cancer progression.

Many cells bind to components of the extracellular matrix. Cell adhesion can occur in two ways; by focal adhesions, connecting the ECM to actin filaments of the cell, and hemidesmosomes, connecting the ECM to intermediate filaments such as keratin. This cell-to-ECM adhesion is regulated by specific cell-surface cellular adhesion molecules (CAM) known as integrins. Integrins are cell-surface proteins that bind cells to ECM structures, such as fibronectin and laminin, and also to integrin proteins on the surface of other cells.

Components of the ECM are produced intracellularly by resident cells and secreted into the ECM via exocytosis. Once secreted, they then aggregate with the existing matrix. The ECM is composed of an interlocking mesh of fibrous proteins and glycosaminoglycans (GAGs).

Glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) are carbohydrate polymers and mostly attached to extracellular matrix proteins to form proteoglycans (hyaluronic acid is a notable exception; see below). Proteoglycans have a net negative charge that attracts positively charged sodium ions (Na+), which attracts water molecules via osmosis, keeping the ECM and resident cells hydrated. Proteoglycans may also help to trap and store growth factors within the ECM.

Collagens are the most abundant protein in the ECM. In fact, collagen is the most abundant protein in the human body and accounts for 90% of bone matrix protein content. Collagens are present in the ECM as fibrillar proteins and give structural support to resident cells. Collagen is exocytosed in precursor form (procollagen), which is then cleaved by procollagen proteases to allow extracellular assembly. Disorders such as Ehlers Danlos Syndrome, osteogenesis imperfecta, and epidermolysis bullosa are linked with genetic defects in collagen-encoding genes. The collagen can be divided into several families according to the types of structure they form:

Elastins, in contrast to collagens, give elasticity to tissues, allowing them to stretch when needed and then return to their original state. This is useful in blood vessels, the lungs, in skin, and the ligamentum nuchae, and these tissues contain high amounts of elastins. Elastins are synthesized by fibroblasts and smooth muscle cells. Elastins are highly insoluble, and tropoelastins are secreted inside a chaperone molecule, which releases the precursor molecule upon contact with a fiber of mature elastin. Tropoelastins are then deaminated to become incorporated into the elastin strand. Disorders such as cutis laxa and Williams syndrome are associated with deficient or absent elastin fibers in the ECM.

Fibronectins are glycoproteins that connect cells with collagen fibers in the ECM, allowing cells to move through the ECM. Fibronectins bind collagen and cell-surface integrins, causing a reorganization of the cell’s cytoskeleton to facilitate cell movement. Fibronectins are secreted by cells in an unfolded, inactive form. Binding to integrins unfolds fibronectin molecules, allowing them to form dimers so that they can function properly. Fibronectins also help at the site of tissue injury by binding to platelets during blood clotting and facilitating cell movement to the affected area during wound healing.

Laminins are proteins found in the basal laminae of virtually all animals. Rather than forming collagen-like fibers, laminins form networks of web-like structures that resist tensile forces in the basal lamina. They also assist in cell adhesion. Laminins bind other ECM components such as collagens and nidogens.

5.4 Cell Junctions

Cell junctions (or intercellular bridges) are a class of cellular structures consisting of multiprotein complexes that provide contact or adhesion between neighboring cells or between a cell and the extracellular matrix in animals. They also maintain the paracellular barrier of epithelia and control paracellular transport. Cell junctions are especially abundant in epithelial tissues. Combined with cell adhesion molecules and extracellular matrix, cell junctions help hold animal cells together.

Cell junctions are also especially important in enabling communication between neighboring cells via specialized protein complexes called communicating (gap) junctions. Cell junctions are also important in reducing stress placed upon cells.

In plants, similar communication channels are known as plasmodesmata, and in fungi they are called septal pores.

In vertebrates, there are three major types of cell junction:

- Adherens junctions, desmosomes and hemidesmosomes (anchoring junctions)

- Gap junctions (communicating junction)

- Tight junctions (occluding junctions)

Invertebrates have several other types of specific junctions.

In multicellular plants, the structural functions of cell junctions are instead provided for by cell walls. The analogues of communicative cell junctions in plants are called plasmodesmata.

5.4.1 Anchoring Junctions

Cells within tissues and organs must be anchored to one another and attached to components of the extracellular matrix. Cells have developed several types of junctional complexes to serve these functions, and in each case, anchoring proteins extend through the plasma membrane to link cytoskeletal proteins in one cell to cytoskeletal proteins in neighboring cells as well as to proteins in the extracellular matrix.

Anchoring-type junctions not only hold cells together but provide tissues with structural cohesion. These junctions are most abundant in tissues that are subject to constant mechanical stress such as skin and heart.

5.4.2 Desmosomes

Desmosomes, also termed as maculae adherentes, can be visualized as rivets through the plasma membrane of adjacent cells. Intermediate filaments composed of keratin or desmin are attached to membrane-associated attachment proteins that form a dense plaque on the cytoplasmic face of the membrane. Cadherin molecules form the actual anchor by attaching to the cytoplasmic plaque, extending through the membrane and binding strongly to cadherins coming through the membrane of the adjacent cell.

5.4.3 Hemidesmosomes

Hemidesmosomes form rivet-like links between cytoskeleton and extracellular matrix components such as the basal laminae that underlie epithelia. Like desmosomes, they tie to intermediate filaments in the cytoplasm, but in contrast to desmosomes, their transmembrane anchors are integrins rather than cadherins.

5.4.4 Adherens Junctions

Adherens junctions share the characteristic of anchoring cells through their cytoplasmic actin filaments. Similarly to desmosomes and hemidesmosomes, their transmembrane anchors are composed of cadherins in those that anchor to other cells and integrins in those that anchor to extracellular matrix. There is considerable morphologic diversity among adherens junctions. Those that tie cells to one another are seen as isolated streaks or spots, or as bands that completely encircle the cell. The band-type of adherens junctions is associated with bundles of actin filaments that also encircle the cell just below the plasma membrane. Spot-like adherens junctions help cells adhere to extracellular matrix both in vivo and in vitro where they are called focal adhesions. The cytoskeletal actin filaments that tie into adherens junctions are contractile proteins and in addition to providing an anchoring function, adherens junctions are thought to participate in folding and bending of epithelial cell sheets. Thinking of the bands of actin filaments as being similar to ‘drawstrings’ allows one to envision how contraction of the bands within a group of cells would distort the sheet into interesting patterns

5.4.5 Communicating (gap) Junctions

Communicating junctions, or gap junctions allow for direct chemical communication between adjacent cellular cytoplasm through diffusion without contact with the extracellular fluid. This is possible due to six connexin proteins interacting to form a cylinder with a pore in the centre called a connexon. The connexon complexes stretches across the cell membrane and when two adjacent cell connexons interact, they form a complete gap junction channel. Connexon pores vary in size, polarity and therefore can be specific depending on the connexin proteins that constitute each individual connexon. Whilst variation in gap junction channels do occur, their structure remains relatively standard, and this interaction ensures efficient communication without the escape of molecules or ions to the extracellular fluid.

Gap junctions play vital roles in the human body, including their role in the uniform contractile of the heart muscle. They are also relevant in signal transfers in the brain, and their absence shows a decreased cell density in the brain. Retinal and skin cells are also dependent on gap junctions in cell differentiation and proliferation.

5.4.6 Tight Junctions

Found in vertebrate epithelia, tight junctions act as barriers that regulate the movement of water and solutes between epithelial layers. Tight junctions are classified as a paracellular barrier which is defined as not having directional discrimination; however, movement of the solute is largely dependent upon size and charge. There is evidence to suggest that the structures in which solutes pass through are somewhat like pores.

Physiological pH plays a part in the selectivity of solutes passing through tight junctions with most tight junctions being slightly selective for cations. Tight junctions present in different types of epithelia are selective for solutes of differing size, charge, and polarity.

5.4.7 Cell Junction Molecules

The molecules responsible for creating cell junctions include various cell adhesion molecules. There are four main types: selectins, cadherins, integrins, and the immunoglobulin superfamily.

Selectins are cell adhesion molecules that play an important role in the initiation of inflammatory processes. The functional capacity of selectin is limited to leukocyte collaborations with vascular endothelium. There are three types of selectins found in humans; L-selectin, P-selectin and E-selectin. L-selectin deals with lymphocytes, monocytes and neutrophils, P-selectin deals with platelets and endothelium and E-selectin deals only with endothelium. They have extracellular regions made up of an amino-terminal lectin domain, attached to a carbohydrate ligand, growth factor-like domain, and short repeat units (numbered circles) that match the complementary binding protein domains.

Cadherins are calcium-dependent adhesion molecules. Cadherins are extremely important in the process of morphogenesis – fetal development. Together with an alpha-beta catenin complex, the cadherin can bind to the microfilaments of the cytoskeleton of the cell. This allows for homophilic cell–cell adhesion. The β-catenin–α-catenin linked complex at the adherens junctions allows for the formation of a dynamic link to the actin cytoskeleton.

Integrins act as adhesion receptors, transporting signals across the plasma membrane in multiple directions. These molecules are an invaluable part of cellular communication, as a single ligand can be used for many integrins. Unfortunately these molecules still have a long way to go in the ways of research.

Immunoglobulin superfamily are a group of calcium independent proteins capable of homophilic and heterophilic adhesion. Homophilic adhesion involves the immunoglobulin-like domains on the cell surface binding to the immunoglobulin-like domains on an opposing cell’s surface while heterophilic adhesion refers to the binding of the immunoglobulin-like domains to integrins and carbohydrates instead.

Cell adhesion is a vital component of the body. Loss of this adhesion effects cell structure, cellular functioning and communication with other cells and the extracellular matrix and can lead to severe health issues and diseases.