15 The Human Genome

In this lab session, we will take a closer look at the human genome and known variations that distinguish different populations and variations that have been linked to increased risk for certain diseases.

The human genome is the complete set of nucleic acid sequences for humans, encoded as DNA within the 23 chromosome pairs in cell nuclei and in a small DNA molecule found within mitochondria. The human genome includes both protein-coding DNA genes and noncoding DNA. The haploid human genome in egg and sperm cells consists of more than three billion DNA base pairs (Table 15.1), while the diploid genome in somatic cells has twice the DNA content. The Human Genome Project (HGP) produced the first (almost) complete sequence of the human genome, with the first draft sequence and initial analysis being published in 2001.

15.1 The Human Genome Project

The Human Genome Project was an international scientific research project with the goal of determining the sequence of nucleotide base pairs that make up human DNA, and of identifying and mapping all of the genes of the human genome from both a physical and a functional standpoint. After the idea was picked up in 1984 by the US government when the planning started, the project formally launched in 1990 and was declared complete in 2003. Funding came from the US government through the National Institutes of Health (NIH) as well as numerous other groups from around the world. A parallel project was conducted outside government by the Celera Corporation, or Celera Genomics, which was formally launched in 1998. Most of the government-sponsored sequencing was performed in twenty universities and research centers in the United States, the United Kingdom, Japan, France, Germany, Spain and China.

The Human Genome Project originally aimed to map the nucleotides contained in a human haploid reference genome (more than three billion). The project was not able to sequence all the DNA found in human cells. It sequenced only euchromatic regions of the genome, which make up 92% of the human genome. The other regions, called heterochromatic, are found in centromeres and telomeres, and were not sequenced under the project. An initial rough draft of the human genome was available in June 2000 and by February 2001 a working draft had been completed and published followed by the final sequencing mapping of the human genome on April 14, 2003. Although this was reported to cover 99% of the euchromatic human genome with 99.99% accuracy, a major quality assessment of the human genome sequence was published on May 27, 2004 indicating over 92% of sampling exceeded 99.99% accuracy which was within the intended goal. Further analyses and papers on the HGP continue to occur.

The most recent official version of the human genome sequence is the Dec. 2013 (GRCh38/hg38) assembly of the human genome (hg38, GRCh38 Genome Reference Consortium Human Reference 38 (GCA_000001405.15)). The Dec. 2013 human reference sequence (GRCh38) was produced by the Genome Reference Consortium.

An assembly is a set of chromosomes, unlocalized and unplaced (random) sequences and alternate loci used to represent an organism’s genome. Most current assemblies are a haploid representation of an organism’s genome, although some loci may be represented more than once. The human genome reference assembly has been obtained from multiple individuals. The haploid assembly does not represent a single haplotype, but rather a mixture of haplotypes. As sequencing technology evolves, it is anticipated that diploid sequences representing an individual’s genome will become available.

A haplotype (haplo: from Ancient Greek ὰπλόος (haplos, single, simple)) is a contiguous section of closely linked segments of DNA within the larger genome that tend to be inherited together as a unit on a single chromosome. Haplotypes have no defined size and can refer to anything from a few closely linked loci up to an entire chromosome. The term is also used to describe groups of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that are statistically associated.

The term ‘haplogroup’ refers to the SNP/unique-event polymorphism (UEP) mutations that represent the clade to which a collection of particular human haplotypes belong. (Clade here refers to a set of haplotypes sharing a common ancestor.) A haplogroup is a group of similar haplotypes that share a common ancestor with a single-nucleotide polymorphism mutation. Mitochondrial DNA passes along a maternal lineage hat can date back thousands of years. Similarly, the Y-chromosome passes along the paternal lineage.

A chromosome assembly represents a relatively complete pseudo-molecule assembled from smaller sequences (components) that represent a biological chromosome. Relatively complete implies that some gaps may still be present in the assembly (e.g. there are still gaps in the human genome assembly), but independent measures suggest that most of the sequence is represented by sequenced bases. An unlocalized sequence is a sequence found in an assembly that is associated with a specific chromosome but cannot be ordered or oriented on that chromosome. An unplaced sequence is a sequence found in an assembly that is not associated with any chromosome.

Assemblies are built from components, which in turn are joined to form contigs, which are used to build scaffolds (definitions of these and other relevant terms can be found on the GRC web site).

| Chromosome | Total length | Ungapped length |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 248,956,422 | 231,223,641 |

| 2 | 242,193,529 | 240,863,511 |

| 3 | 198,295,559 | 198,255,541 |

| 4 | 190,214,555 | 189,962,376 |

| 5 | 181,538,259 | 181,358,067 |

| 6 | 170,805,979 | 170,078,524 |

| 7 | 159,345,973 | 158,970,135 |

| 8 | 145,138,636 | 144,768,136 |

| 9 | 138,394,717 | 122,084,564 |

| 10 | 133,797,422 | 133,263,006 |

| 11 | 135,086,622 | 134,634,058 |

| 12 | 133,275,309 | 133,137,821 |

| 13 | 114,364,328 | 97,983,128 |

| 14 | 107,043,718 | 91,660,769 |

| 15 | 101,991,189 | 85,089,576 |

| 16 | 90,338,345 | 83,378,703 |

| 17 | 83,257,441 | 83,481,871 |

| 18 | 80,373,285 | 80,089,650 |

| 19 | 58,617,616 | 58,440,758 |

| 20 | 64,444,167 | 63,944,268 |

| 21 | 46,709,983 | 40,088,623 |

| 22 | 50,818,468 | 40,181,019 |

| X | 156,040,895 | 154,893,034 |

| Y | 57,227,415 | 26,452,288 |

| MT | 16,569 | |

| Unplaced | 4,485,509 | 4,328,403 |

| Genome | 3,099,734,149 | 2,948,611,470 |

HGP scientists used white blood cells from the blood of two male and two female donors (randomly selected from 20 of each) each donor yielding a separate DNA library. One of these libraries (RP11) was used considerably more than others, due to quality considerations. More than 70% of the reference genome produced by the public HGP came from RP11, a single anonymous male donor from Buffalo, New York (code name RP11).

The genome was broken into smaller pieces; approximately 150,000 base pairs in length. These pieces were then ligated into a type of vector known as “bacterial artificial chromosomes”, or BACs, which are derived from bacterial chromosomes which have been genetically engineered. The vectors containing the genes can be introduced into bacteria where they are copied by the bacterial DNA replication machinery. Each of these pieces was then sequenced separately as a small “shotgun” project and then assembled. The larger, 150,000 base pairs go together to create chromosomes. This is known as the “hierarchical shotgun” approach, because the genome is first broken into relatively large chunks, which are then mapped to chromosomes before being selected for sequencing.

The “genome” of any given individual is unique; mapping the “human genome” involved sequencing a small number of individuals and then assembling these together to get a complete sequence for each chromosome. Therefore, the finished human genome is a mosaic, not representing any one individual. In fact, we now know that there is variation in the genomes of individual cells in any one human. The implications of this recent finding for human health will keep scientists busy for a long time.

15.2 Public-Private Competition Around The Human Genome Project

In 1998, a privately funded quest to sequence the human genome was launched by the American researcher Craig Venter, and his firm Celera Genomics. Venter was a scientist at the NIH during the early 1990s when the project was initiated. The $300,000,000 Celera effort was intended to proceed at a faster pace and at a fraction of the cost of the roughly $3 billion publicly funded project. The Celera approach was able to proceed at a much more rapid rate, and at a lower cost than the public project because it relied upon data made available by the publicly funded project.

Celera used a technique called whole genome shotgun sequencing, employing pairwise end sequencing, which had been used to sequence bacterial genomes of up to six million base pairs in length, but not for anything nearly as large as the three billion base pair human genome.

Celera initially announced that it would seek patent protection on “only 200-300” genes, but later amended this to seeking “intellectual property protection” on “fully-characterized important structures” amounting to 100-300 targets. The firm eventually filed preliminary (“place-holder”) patent applications on 6,500 whole or partial genes. Celera also promised to publish their findings in accordance with the terms of the 1996 “Bermuda Statement”, by releasing new data annually (the HGP released its new data daily), although, unlike the publicly funded project, they would not permit free redistribution or scientific use of the data. The publicly funded competitors were compelled to release the first draft of the human genome before Celera for this reason. On July 7, 2000, the UCSC Genome Bioinformatics Group released a first working draft on the web. The scientific community downloaded about 500 GB of information from the UCSC genome server in the first 24 hours of free and unrestricted access.

In March 2000, US President Clinton announced that the genome sequence could not be patented, and should be made freely available to all researchers. The statement sent Celera’s stock plummeting and dragged down the biotechnology-heavy Nasdaq. The biotechnology sector lost about $50 billion in market capitalization in two days.

Although the working draft was announced in June 2000, it was not until February 2001 that Celera and the HGP scientists published details of their drafts. Special issues of Nature (which published the publicly funded project’s scientific paper)[43] and Science (which published Celera’s paper) described the methods used to produce the draft sequence and offered analysis of the sequence. These drafts covered about 83% of the genome (90% of the euchromatic regions with 150,000 gaps and the order and orientation of many segments not yet established). In February 2001, at the time of the joint publications, press releases announced that the project had been completed by both groups. Improved drafts were announced in 2003 and 2005, filling in to approximately 92% of the sequence currently.

15.3 Genome Annotation

The process of identifying the boundaries between genes and other features in a raw DNA sequence is called genome annotation and is in the domain of bioinformatics. Annotation of genes (coding sequences, CDS) is provided by multiple public resources, using different methods, and resulting in information that is similar but not always identical. The Consensus CDS (CCDS) project is a collaborative effort to identify a core set of protein coding regions that are consistently annotated and of high quality and support convergence towards a standard set of gene annotations. While expert biologists make the best annotators, their work proceeds slowly, and computer programs are increasingly used to meet the high-throughput demands of genome sequencing projects. Beginning in 2008, a new technology known as RNA-seq was introduced that allowed scientists to directly sequence the messenger RNA in cells. This replaced previous methods of annotation, which relied on inherent properties of the DNA sequence, with direct measurement, which was much more accurate. Today, annotation of the human genome and other genomes relies primarily on deep sequencing of the transcripts in every human tissue using RNA-seq. These experiments have revealed that over 90% of genes contain at least one and usually several alternative splice variants, in which the exons are combined in different ways to produce 2 or more gene products from the same locus.

| Name | GC (%) | Protein | rRNA | tRNA | Other RNA | Gene | Pseudogene |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chr 1 | 42.3 | 11,321 | 17 | 90 | 4,457 | 5,109 | 1,386 |

| Chr 2 | 40.3 | 8,291 | - | 7 | 3,728 | 3,871 | 1,181 |

| Chr 3 | 39.7 | 7,150 | - | 4 | 2,782 | 2,990 | 900 |

| Chr 4 | 38.3 | 4,599 | - | 1 | 2,193 | 2,441 | 803 |

| Chr 5 | 39.5 | 4,729 | - | 17 | 2,194 | 2,592 | 778 |

| Chr 6 | 39.6 | 5,522 | - | 138 | 2,453 | 3,005 | 882 |

| Chr 7 | 40.7 | 5,112 | - | 22 | 2,330 | 2,792 | 911 |

| Chr 8 | 40.2 | 4,199 | - | 4 | 2,011 | 2,165 | 671 |

| Chr 9 | 42.3 | 4,699 | - | 3 | 2,222 | 2,270 | 706 |

| Chr 10 | 41.6 | 5,429 | - | 3 | 2,133 | 2,179 | 640 |

| Chr 11 | 41.6 | 6,394 | - | 13 | 2,336 | 2,924 | 829 |

| Chr 12 | 40.8 | 5,975 | - | 9 | 2,457 | 2,526 | 691 |

| Chr 13 | 40.2 | 2,056 | - | 4 | 1,243 | 1,385 | 475 |

| Chr 14 | 42.2 | 3,501 | - | 18 | 1,704 | 2,065 | 585 |

| Chr 15 | 43.4 | 3,623 | - | 9 | 1,810 | 1,824 | 554 |

| Chr 16 | 45.1 | 4,625 | - | 27 | 1,761 | 1,938 | 469 |

| Chr 17 | 45.3 | 6,226 | - | 33 | 2,243 | 2,450 | 556 |

| Chr 18 | 39.8 | 2,029 | - | 1 | 996 | 984 | 295 |

| Chr 19 | 47.9 | 6,750 | - | 6 | 1,877 | 2,499 | 523 |

| Chr 20 | 43.9 | 2,904 | - | - | 1,308 | 1,358 | 338 |

| Chr 21 | 42.2 | 1,297 | 12 | 1 | 707 | 77 | 207 |

| Chr 22 | 47.7 | 2,582 | - | - | 1,014 | 1,189 | 354 |

| Chr X | 39.6 | 3,801 | - | 4 | 1,265 | 2,186 | 875 |

| Chr Y | 45.4 | 324 | - | - | 311 | 580 | 392 |

| MT | 44.4 | 13 | 2 | 22 | - | 37 | - |

| Un | 44.3 | 6,143 | 17 | 161 | 3,437 | 6,543 | 1,878 |

| Coding sequence type | Count |

|---|---|

| Coding genes | 20,376 (incl 612 readthrough) |

| Non coding genes | 22,305 |

| Small non coding genes | 5,363 |

| Long non coding genes | 14,720 (incl 256 readthrough) |

| Misc non coding genes | 2,222 |

| Pseudogenes | 14,692 (incl 7 readthrough) |

| Gene transcripts | 203,903 |

15.4 International HapMap Project

The International HapMap Project was an organization that aimed to develop a haplotype map (HapMap) of the human genome, to describe the common patterns of human genetic variation. HapMap is used to find genetic variants affecting health, disease and responses to drugs and environmental factors. The information produced by the project was made freely available for research.

Four populations were selected for inclusion in the HapMap: 30 adult-and-both-parents Yoruba trios from Ibadan, Nigeria (YRI), 30 trios of Utah residents of northern and western European ancestry (CEU), 44 unrelated Japanese individuals from Tokyo, Japan (JPT) and 45 unrelated Han Chinese individuals from Beijing, China (CHB).

All samples were collected through a community engagement process with appropriate informed consent. The community engagement process was designed to identify and attempt to respond to culturally specific concerns and give participating communities input into the informed consent and sample collection processes.

In phase III, 11 global ancestry groups were assembled: ASW (African ancestry in Southwest USA); CEU (Utah residents with Northern and Western European ancestry from the CEPH collection); CHB (Han Chinese in Beijing, China); CHD (Chinese in Metropolitan Denver, Colorado); GIH (Gujarati Indians in Houston, Texas); JPT (Japanese in Tokyo, Japan); LWK (Luhya in Webuye, Kenya); MEX (Mexican ancestry in Los Angeles, California); MKK (Maasai in Kinyawa, Kenya); TSI (Tuscans in Italy); YRI (Yoruba in Ibadan, Nigeria).

Through this research millions of SNPs were discovered and many GWAS studies used this dataset in research for disease association. This project was a stepping stone for the 1000 genomes project which utilizes many of the same populations.

15.5 The Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Database (dbSNP) of Nucleotide Sequence Variation

The Single Nucleotide Polymorphism database (dbSNP) is a public-domain archive for a broad collection of simple genetic polymorphisms. This collection of polymorphisms includes single-base nucleotide substitutions (also known as single nucleotide polymorphisms or SNPs), small-scale multi-base deletions or insertions (also called deletion insertion polymorphisms or DIPs), and retroposable element insertions and microsatellite repeat variations (also called short tandem repeats or STRs). Please note that in this chapter, you can substitute any class of variation for the term SNP. Each dbSNP entry includes the sequence context of the polymorphism (i.e., the surrounding sequence), the occurrence frequency of the polymorphism (by population or individual), and the experimental method(s), protocols, and conditions used to assay the variation.

The Reference SNP cluster ID (rsid) is an accession number used to refer to specific SNPs in the database.

15.6 The 1000 Genomes Project

The 1000 Genomes Project launched in January 2008, is an international research effort to establish by far the most detailed catalogue of human genetic variation (Table 15.4). Scientists planned to sequence the genomes of at least one thousand anonymous participants from a number of different ethnic groups within the following three years, using newly developed technologies which were faster and less expensive. In 2015, two papers in the journal Nature reported results and the completion of the project and opportunities for future research. Many rare variations, restricted to closely related groups, were identified, and eight structural-variation classes were analyzed.

The project unites multidisciplinary research teams from institutes around the world, including China, Italy, Japan, Kenya, Nigeria, Peru, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The team have been contributing to the enormous sequence dataset and to a refined human genome map, which are freely accessible through public databases to the scientific community and the general public alike. The International Genome Sample Resource (IGSR) was established at the European Bioinformatics Institute (EMBL-EBI) in January 2015. The resource was established with three main aims, to:

- Ensure maximal usefulness and relevance of the existing 1000 Genomes data resources

- Extend the resource for the existing populations

- Expand the resource to new populations

By providing an overview of all human genetic variation, the consortium has generated a valuable tool for all fields of biological science, especially in the disciplines of genetics, medicine, pharmacology, biochemistry, and bioinformatics.

| Superpopulation | Description | Population | Samples |

|---|---|---|---|

| AFR | African Ancestry in Southwest US | ASW | 112 |

| AFR | African Caribbean in Barbados | ACB | 123 |

| AFR | Esan in Nigeria | ESN | 173 |

| AFR | Gambian in Western Division, The Gambia - Fula | GWF | 100 |

| AFR | Gambian in Western Division, The Gambia - Mandinka | GWD | 280 |

| AFR | Gambian in Western Division, The Gambia - Wolof | GWW | 100 |

| AFR | Luhya in Webuye, Kenya | LWK | 116 |

| AFR | Mende in Sierra Leone | MSL | 128 |

| AFR | Yoruba in Ibadan, Nigeria | YRI | 186 |

| AMR | Colombian in Medellin, Colombia | CLM | 148 |

| AMR | Mexican Ancestry in Los Angeles, California | MXL | 107 |

| AMR | Peruvian in Lima, Peru | PEL | 130 |

| AMR | Puerto Rican in Puerto Rico | PUR | 150 |

| EAS | Chinese Dai in Xishuangbanna, China | CDX | 109 |

| EAS | Han Chinese in Beijing, China | CHB | 112 |

| EAS | Han Chinese South | CHS | 171 |

| EAS | Japanese in Tokyo, Japan | JPT | 105 |

| EAS | Kinh in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam | KHV | 124 |

| EUR | British in England and Scotland | GBR | 107 |

| EUR | Finnish in Finland | FIN | 105 |

| EUR | Iberian populations in Spain | IBS | 162 |

| EUR | Toscani in Italy | TSI | 112 |

| EUR | Utah residents (CEPH) with Northern and Western European ancestry | CEU | 183 |

| SAS | Bengali in Bangladesh | BEB | 144 |

| SAS | Gujarati Indian in Houston, TX | GIH | 113 |

| SAS | Indian Telugu in the UK | ITU | 118 |

| SAS | Punjabi in Lahore, Pakistan | PJL | 158 |

| SAS | Sri Lankan Tamil in the UK | STU | 128 |

Some basic statistics about the variant sites on the autosomes (chromosomes 1 to 22) and the X chromosome in phase 3 release version 5a from Feb. 20th, 2015 are listed in Table 15.5. The numbering of chromosome locations is based on Genome Reference Consortium Human Build 37 patch release 13 (GRCh37.p13).

| Type | Autosomes | X chromosome |

|---|---|---|

| SNPs | 78136341 | 3246232 |

| indels | 3135424 | 227112 |

| others | 58671 | 2040 |

| multiallelic sites | 416023 | 30994 |

| multiallelic SNP sites | 259370 | 1505 |

| Total | 81271745 | 3468087 |

Figure 15.1: Principle component analysis (PCA) of genetic variation in the 1000 genomes project reveals population stratification. PCA is based on 473,964 autosomal variants with a minor allele frequency greater than 10% in 2504 people from 5 superpopulations.

15.7 Personal genomics

Personal genomics or consumer genetics is the branch of genomics concerned with the sequencing, analysis and interpretation of the genome of an individual. The genotyping stage employs different techniques, including single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) analysis chips (typically 0.02% of the genome), or partial or full genome sequencing. Once the genotypes are known, the individual’s variations can be compared with the published literature to determine likelihood of trait expression, ancestry inference and disease risk.

Automated high-throughput sequencers have increased the speed and reduced the cost of sequencing, making it possible to offer genetic testing to consumers for less than $1,000. The emerging market of direct-to-consumer genome sequencing services has brought new questions about both the medical efficacy and the ethical dilemmas associated with widespread knowledge of individual genetic information. Companies like Ancestry and 23andMe, however, do not sequence your DNA but perform “genotyping” using DNA microarrays (“genotyping chips”) to determine SNPs at hundreds of thousands of locations in your genome. Ancestry, for example state that they examine some 700,000 SNPs.

Starting in 2005 as a pilot experiment with 10 individuals, the Harvard Personal Genome Project (Harvard PGP) pioneered a new form of genomics research. The main goal of the project is to allow scientists to connect human genetic information (human DNA sequence, gene expression, associated microbial sequence data, etc) with human trait information (medical information, biospecimens and physical traits) and environmental exposures.

PGP participants consent to publicly share their genomic and trait data in a free and open manner to be used for unimpeded research and other scientific, patient care and commercial purposes worldwide. Consistent with this consent, the project organizers seek to lower as many barriers as possible to access PGP data and cells to empower and engage the scientific community to drive new knowledge about human biology. The project now has over 5,000 participants.

15.8 Viewing The Human Genome

15.8.1 Experimental Procedures

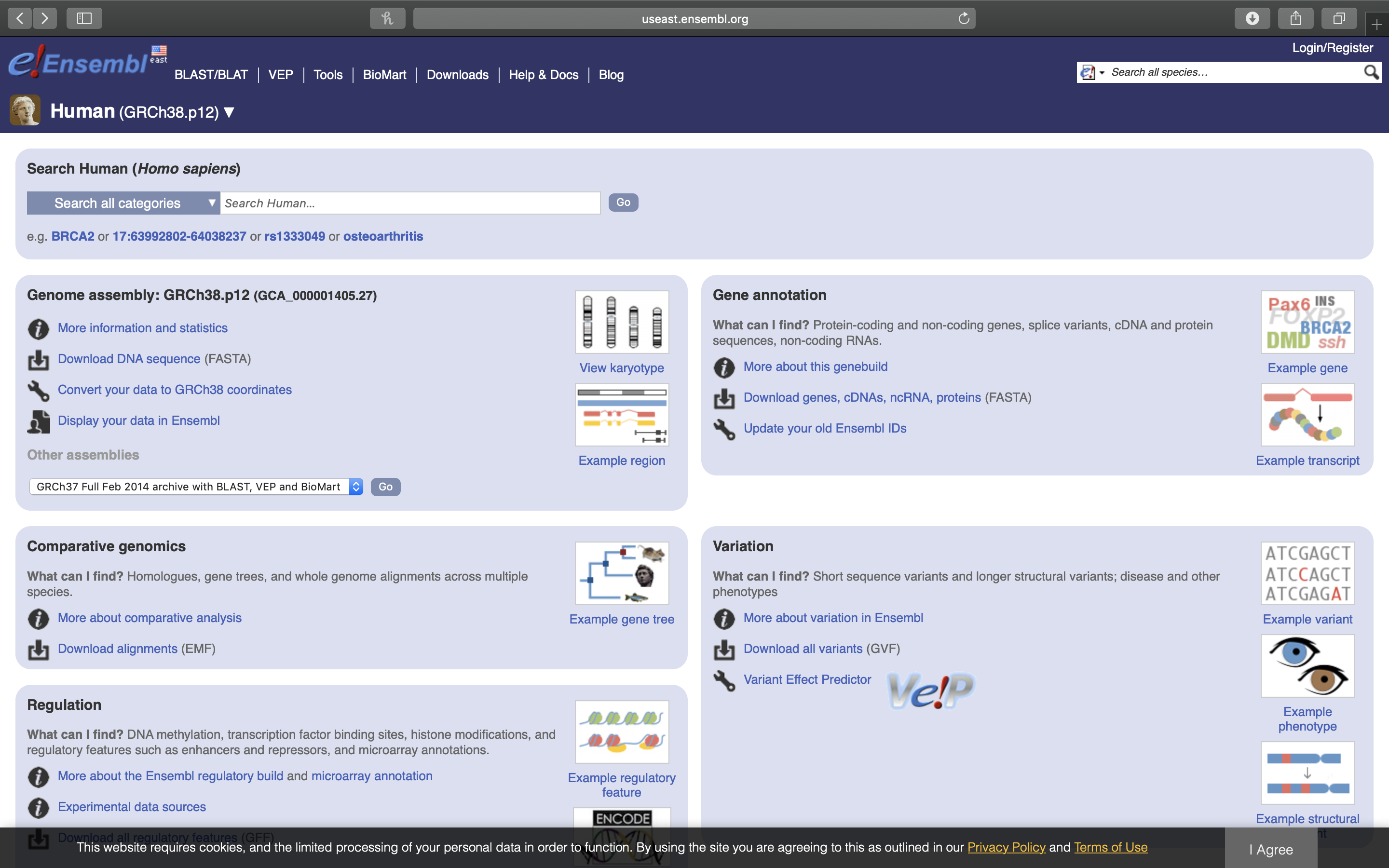

- Open a web browser and go to the Ensemble genome browser (Fig. 15.2). This site provides a data set based on the December 2013 Homo sapiens high coverage assembly GRCh38 from the Genome Reference Consortium.

Figure 15.2: The Ensembl genome browser web page.

15.9 Review Questions

- What is the length of the human genome (in base pairs)?

- What is a genome assembly?

- What is genome annotation?

- How many genes are in the human genome?